Britain isn't working (Part 2 of 3)

Understanding the rise of Reform

The second of three pieces this week on understanding Reform’s success in last week’s Local Elections, why Britain Isn’t Working - and why this is driving people’s search for an alternative, any alternative. Part One can be read here and Part Three here.

In the first of this series we looked at how the classic relationship between tax and public services has broken down, with the tax take increasing but public services getting worse. We saw that people feel this across almost every area of life, from the NHS to crime to bin collection - as well as many feeling more ‘cultural’ concerns going ignored, particularly on immigration and small boats.

People are searching for an alternative - any alternative. They voted for Brexit in 2016 (and again in 2019), searched for it in Labour in 2024, and are now turning against both the main parties. This isn’t because Reform has a detailed policy platform they like - it doesn’t - but because they are angry and upset, they are crying out for change - and having been repeatedly let down, they are willing to try one more thing.

We looked at how the reason for the decline isn’t solely due to demographic change or Baumol’s cost disease, but because both parties have, in practice, cleaved to a core set of pro-Boomer and pro-Anywhere policies that have collectively immiserated the country.

Last week we saw that:

Long-term failure to build enough homes has priced a generation out of ownership, sent rent costs spiralling and broken the social contract between hard work and home ownership.

Mass low-skilled immigration directly decreases GDP per capita, as well as putting (more) pressure on house prices, depresssing wages and weakening social cohesion.

The numbers on out-of-work benefits is soaring, with mental health a major component of this. This is a direct cost and also takes people out of the workforce who could be paying tax. Labour’s reforms only make the bill rise more slowly.

The UK has some of the highest energy costs in the western world. This increases the cost of living for households, increases costs for business and deters companies from investing. The issue is less subsidising renewables, but more failing to maintain oil, gas and nuclear through the transition.

In Part Two we’ll look at the next four of these policies:

Not building enough homes

Addiction to mass immigration - and failing to control the border

Permitting the numbers on out-of-work benefits to soar

Tolerating and exacerbating high energy costs

Uncontrolled university expansion

The spiralling cost of regulation

Not facing up to the rise in mental health and special educational needs.

Hollowing out Local Authority budgets

Encouraging the growth of radical identity politics

Failing to resource the criminal justice system

A maximalist commitment to human rights law

Maintaining the state pension triple-lock.

Uncontrolled university expansion1

UK undergraduate numbers have steadily increased this century - driven first by Tony Blair’s pledge to have half of young people going to higher education, and turbo-charged by the decision of the Coalition to remove number controls that had been in place for decades.

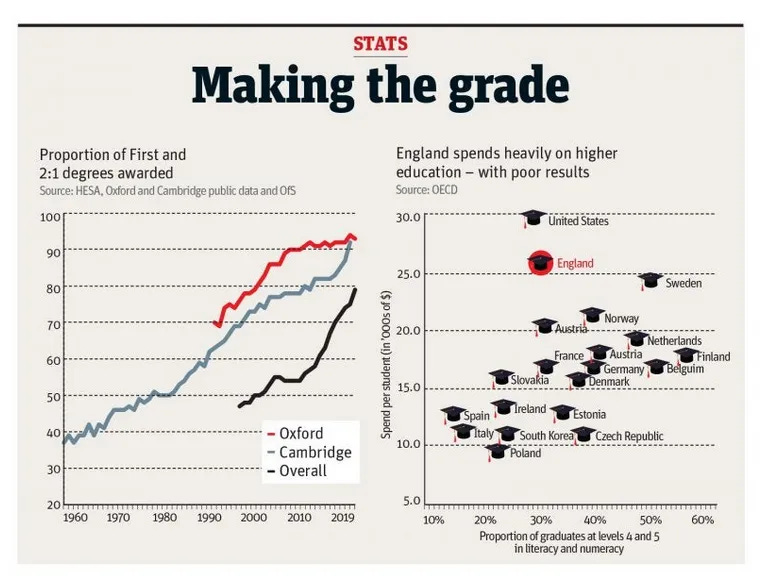

Despite this, grade inflation has soared:

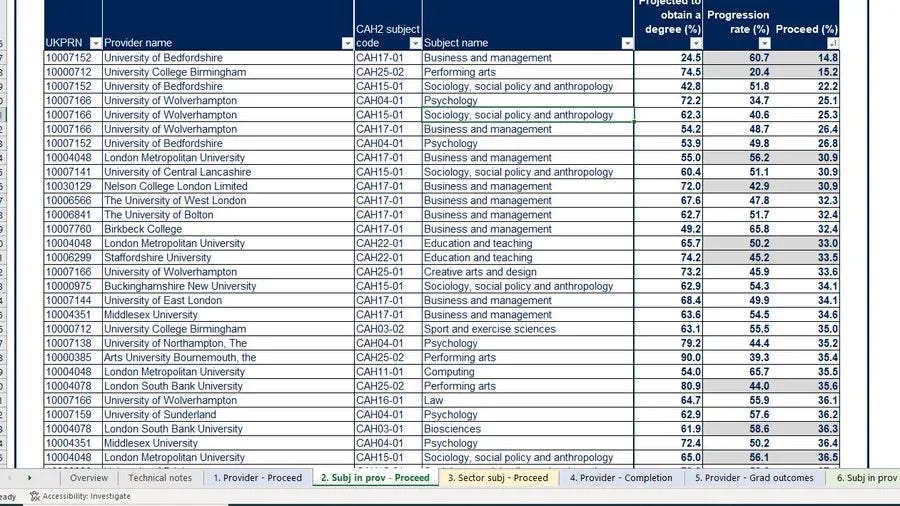

And many courses have high drop-out rates and low progression to graduate jobs:

Although approximately 70% of the cost of university is recouped from graduates in the form of student loan repayments, this itself directly contributes to the immiseration of the UK. With a graduate on the minimum wage now paying an effective marginal tax rates of 45% (including student loan repayments), it is no wonder that many younger people look for alternatives to the two main parties, who are currently united in their support for the debt-driven model of mass participation and expansion. What’s more, the reduction in consumer spending power will directly depress growth - as well as making it harder for these individuals to get on the housing ladder (see Part One).

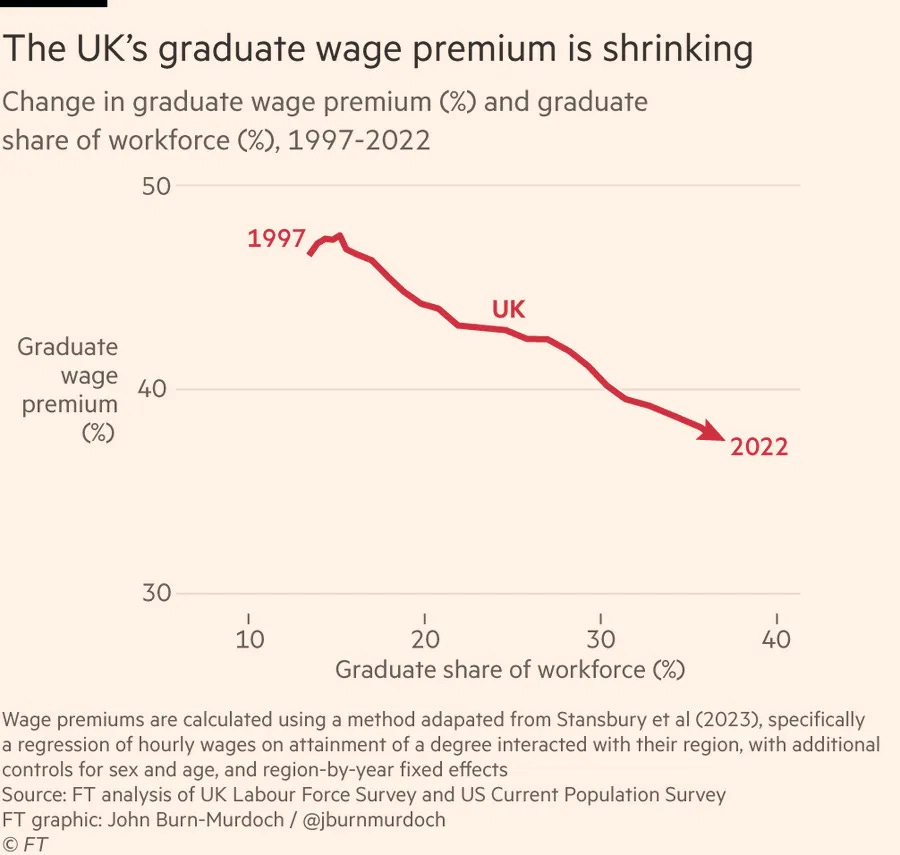

If university expansion was making the country richer, then the debt might be worth it. But it doesn’t appear to be. At least one in five graduates (15% of women, 25% of men) would have been better off had they not gone to university2, and the graduate premium has been steadily declining. A recent report has suggested that this may be driven in part by the addition of large numbers of graduates with low prior academic achievement, who would not previously have gone to university and (on average) gain little or no benefit from doing so.

Over a third (36%) of graduates are in non-graduate jobs, suggesting we don’t need nearly as many as we produce20. In the past, paramedics, social workers, journalists, police-officers and even bankers often used to enter the workforce without a degree, either at 18 or after some training in a local college. Yet now these roles are becoming - either as a direct requirement or simply by a changing norm - increasingly dominated by graduates.

We also have to consider the opportunity cost:

Of scarce government funds being spent on university expansion, when they could be spent on transport infrastructure, energy generation, business support or other things that would increase our competitiveness and growth.3

Of taking people out of the labour market for dubious personal or national benefit, particularly when labour is in short supply.

Of taking money from people in debt repayments, which they could use in ways they would value more.

And perhaps worst of all, the decision to focus so relentlessly on higher education has led to a major reduction in the funding and places available for further education:

Even if the benefit from the average person going to university is still positive, the benefit from the marginal person going is not - and has not been for some time. Mass university expansion is making the country poorer - and is also producing a legion of young people who are understandably disgruntled that they have been missold a dream, one which has not delivered the career opportunities or financial rewards they were promised, but has left them with a lifetime of debt.

Spiralling regulation

Top tip to any current or future MPs or government advisers reading this: including ‘regulatory reform’ in the name of a department (the short-lived ‘BERR’) or a Bill (many such cases) will never inject the sense of dynamism you are looking for. And yet, regulation is incredibly important - and increasingly strangling our economy.

Nobody would want to get rid of all regulation, some of which has important purposes. But year after year, the burden of regulation increases, imposed by government departments, agencies and regulators. There has been a broad increase in business regulations across most sectors, the burden of regulation has increased, as has the head count at major regulators increased. The Regulatory Policy Committee produces an annual estimate of the additional regulatory burdens imposed by government in the previous year, which typically totals in the billions or the tens of billions. Every penny spent on complying with regulation is one that cannot be spent producing products, investing or increasing the salaries of those engaged in a company’s core business.

Nor is regulation solely confined to the private sector. Regulations on schools, hospitals and other public sector bodies divert staff and funding from front-line delivery into compliance. Schools alone have thousands of pages of statutory guidance and compliance procedures to abide by. Twenty-five years ago, my school - a mid-sized secondary school with 140 pupils a year - had a couple of people doing admin; now it has a large ‘admin block’. Similar burdens apply across the public sector.

Why has this increased so much? One reason is the rise of ‘safetyism’, where preventing harm - of any sort - is made the primary virtue. Haidt

Safety is good, of course, and keeping others safe from harm is virtuous, but virtues can become vices when carried to extremes. ‘Safetyism’ refers to a culture or belief system in which safety has become a sacred value, which means that people become unwilling to make trade-offs demanded by other practical and moral concerns. “Safety” trumps everything else, no matter how unlikely or trivial the potential danger.

The Coddling of the American Mind (Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt)

Other reasons relateto the incentives - upon politicians, civil servants and regulators.

Many regulators have statutory duties that require them to consider a specific objective, without considering whether measures to achieve it would be proportionate, or to weigh it against other things of value. Thus we have that Natural England which, in 2017, introduced new rules on ‘nutrient neutrality’ which are estimated to be holding up 100,000 new homes. Introduced at a stroke of a pen by a regulator, it can only be repealed by an Act of Parliament - which requires time, political capital and attention, all of which are too frequently in scarce supply.

It is always easier to campaign for a new law. For my sins, I helped to establish one of our more obscure Quangos, the Groceries Code Adjudicator4, a job I enjoyed greatly, but which it is hard to say has done much other than to make our weekly supermarket marginally more expensive. Yet it was in the Conservative and Liberal Democrat Manifestos in 2010 - and thus a shoe-in for the Coalition Agreement.

It is much harder to gain credit for repealing regulation that is bad, or unnecessary, or has served its purpose. Firstly, who will care? And what if, there is always the thought, one repeals it and something goes wrong? That could be the end of a political career - or a blot on a top civil servant’s copybook. Much easier not to rock the boat.

When something bad happens, the call goes out that Something Must be Done - and we end up with a new law or regulation. And then, when the hue and cry has moved on, there is no urgency to remove it - and so the law remains.

A good example is Martyn’s Law, begun under the Conservatives and continued under Labour, that requires all venues which may ‘at least occasionally’ host gatherings of 200 people or more to ‘consider how they would respond to a terrorist attack’, introduced after the dreadful Manchester Arena bombing. So now, village and church halls, local sports centres, wedding venues and many other venues - often small businesses or charitably run - will have to create and update policies about responding to terrorism. Does anyone seriously think this will make us safer?

Some of these examples sound large, but others may appear trivial. How hard is it to draw up a new policy? Not so hard, perhaps, but when the regulations keep coming, piled one upon another, the total impact and burden can only be seen via the cumulative assessment of impact, which has become very large indeed.

And so more and more of time and money, whether in the private sector, or in public services, is spent dealing with regulation and compliance, rather than in producing the goods and services that we actually want.

Of course, few people are voting for Reform - or the Lib Dems, or the Greens - because they are upset about too much regulation. But alongside other policies, it is contributing to our productivity challenges, which in turn is leading to the toxic combination of higher taxes and worse public services.

Not facing up to the rise in mental health and special educational needs.

The recorded incidents of mental health issues and diagnoses of various forms of neurodivergence have surged over the last 10-15 years.

At least some of this increase, particularly in mental health, is likely to be real. Jonathan Haidt and others have made an in my view compelling argument that social media is a major cause of this - both directly, and through the displacement of other activities such as outdoor play or in-person human interaction - and many graphs such as the one below can be found on his substack, or in his book The Anxious Generation.5

There is also the very valid point that even if some of these increased are caused by changing attitudes to how we respond to mental health, or different6 approaches to parenting, that does not mean they are not real. The mind is a peculiar thing, and it does what it does, by whatever path it got there.

At the same time though, it seems likely that, for better or worse, we have shifted how we view certain conditions, particularly when it comes to conditions such as ADHD, autism, and various newer syndromes or conditions such as ‘pathological demand avoidance’. While there are undoubtedly some people with severe need, to what extent are we medicalising normal variation within the human condition? While some parents and teachers see diagnosis as a tool to helping them overcome a challenge, many others appear to see it as a reason to tolerate certain behaviours and not change them - as, after all, they are now justified by a diagnosis. Are we really being compassionate when we permit a child to ‘school refuse’ for year after year, accommodating their ‘needs’ by sending specially tailored work home - or are we setting them up to join the growing ranks of those who graduate from education to welfare?

We should also be suspicious that incentives within the system are also driving behaviours. The Health Secretary has suggested that mental health conditions are being overdiagnosed. But if a diagnosis allows parents to unlock more support for their child - or a school to access more funds - then who can blame them for doing so? Approximately a third of children received extra time in exams last year, meaning that was what meant to be an exceptional circumstance is rapidly becoming the norm. Again, the fact that 43% of private school children received extra time, compared to only 27% of those in state schools, should make us suspicious that incentives are driving behaviour, with those with more resources better able to take advantage of the system.

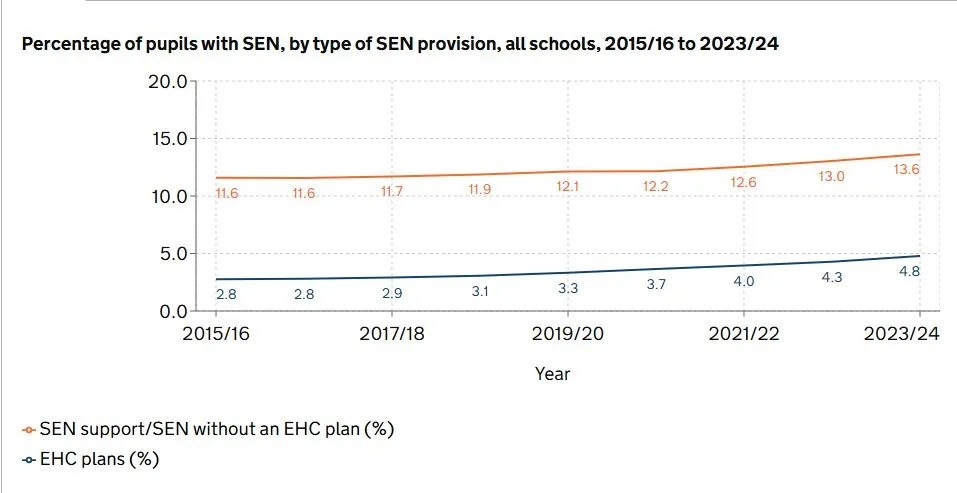

Regardless of whether the changes are real or not, they are driving consequences. SEND budgets in schools and local authorities are under huge pressure, with numbers receiving EHCP plans almost doubling in ten years. As we discussed in Part 1, more than half of the rise in 16-64 year-old claimants is due to mental health health or behavioural conditions, with a sharp increase in the number of young people going straight from education on to disability benefits - primarily for mental health reasons.25 The soaring numbers have also placed tremendous pressure on NHS mental health services, meaning that those in most need have to wait longer for support - and when they get it it is often less than they require.

This is a difficult challenge for any politician to confront. At the heart of every case is a person in distress or in need, often supported by parents or other family members who are sincerely doing what they believe is best - often at serious cost or time to themselves. How we think about and approach matters such as mental health, cognition and parenting is a deeply cultural phenomenon, not something that can be changed with a dictat from Westminster.

And yet the costs - both financial and personal, to those affected - are now becoming so large that face up to it we must.

To the extent that the increases are real, we must get more serious about tackling it at its source. If you believe, as I do, that that is primarily phones and social media, that would mean much more direct action to address that in the way we do other harms such as alcohol, with a range of tools including age-limits, restrictions, taxes, public health campaigns, stigmatisation and more. As it stands, the Government is balking at even the most basic and easiest to implement steps, such as an effective phone ban in schools7. Alternatively, if one thinks that something else is causing it, we should be taking serious steps to address that.

To the extent that the increases reflect changing cultural attitudes, that is much more difficult. But we could at least address some of the symptoms of the problem. More rigour in deciding what we fund, and how much, would alleviate some of the financial pressures, as well as ensuring that interventions are genuinely in people’s long-term interests.8 The welfare system will need to be overhauled, as do the incentives in schools and the exam systems. People may still be able to get a diagnosis for various forms of neurodivergence, but it would become more like a Myers-Briggs test: something that a person might find helpful for self-understanding and personal validation, but not something that - other than in the most severe cases - carried with it an automatic entitlement to additional funding, extra time or other considerations in exams, or eligibility for welfare.

Hollowed out Local Authority Budgets

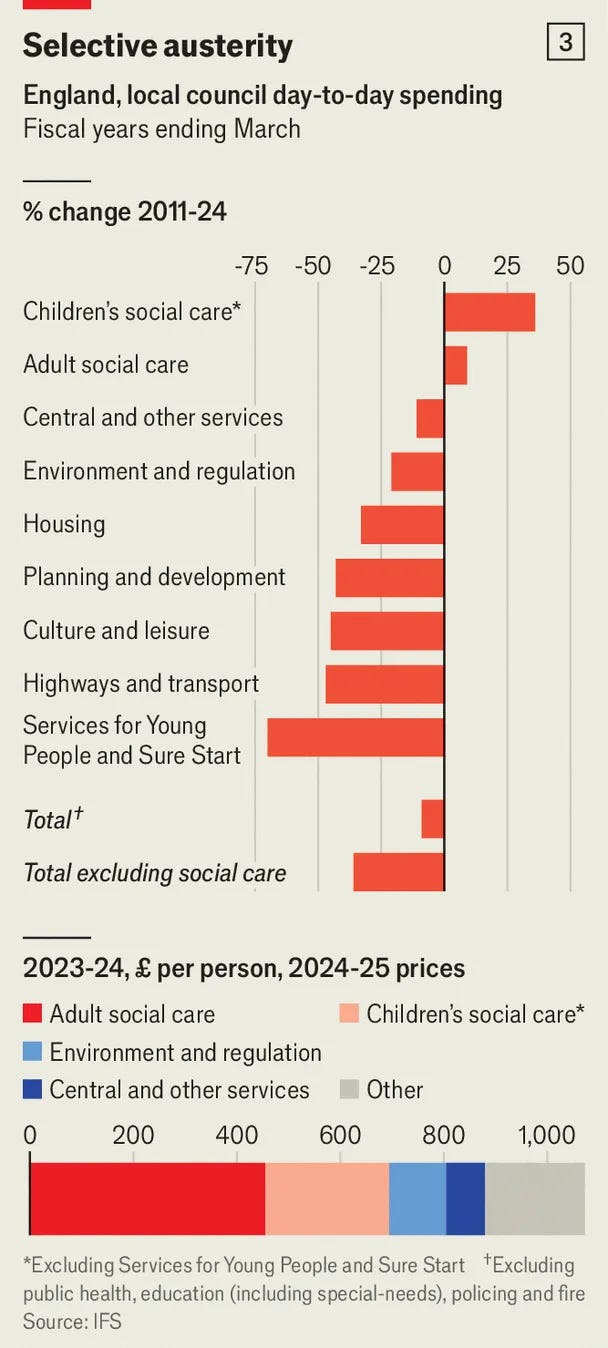

Local authority budgets are down by about 10% in real terms compared to 15 years ago. Government grants have fallen by a lot more, with the difference made up primarily by increases in council tax. While this has had an impact, by far the more significant change is a drastic reshaping of how the budgets are spent:

We can see that social care now makes up a tremendous proportion of council spending - and, as discussed above, SEND spending is taking an increasing chunk of the rest. Every other budget line has been cut, often to the bone - and this means every service or function that most people come into contact with. That manifests as reduced bin collections, closed libraries, dirtier streets, slower planning application approvals and a general deterioration of the amenities in the areas we live.9

At the same time, after near-freezes in the early 2010s, council tax has been going up by 4-5% every year for almost the last decade.

People are paying more for worse services - and in a way which very visibly affects their lives. Council tax is one of the more painful taxes to pay: it does not come out of your paycheck without you seeing it, nor is it invisibly baked into the prices in shops: instead, you get a bill, with the money paid out of post-tax income. And closed libraries and sports centres, shuttered high streets, or 3-weekly bin collections10 are all things that people can see with their own eyes rather than only showing up in national statistics.

The reason for this is statutory duties. Local authorities have certain functions they have to fulfil, with little discretion about how they do so, or how much they spend.11 This has become a major problem with growing, expensive demand-led functions such as social care and SEND which are eating up an increasing proportion of budgets. Things are now at breaking point. Six councils have declared bankruptcy, and a quarter are saying they may need a government bailout to avoid it.

The statutory duties drive a coach and horses through the notion of local democracies in which elected local figures are accountable for delivering the public services that their voters wish - and where communities can choose to vote for higher taxes and better services (or for the candidates that will prioritise the services they consider important) or for lower taxes and more frugal spending. It is a common refrain on the centre-left that local authorities should have greater freedom to raise revenue by putting up taxes more, or from a greater variety of sources. This may or may not be a good idea in the abstract.12 But without reconsidering the role of statutory duties, and restoring greater freedom to local authorities over where and how they spend the moneys they receive, such freedoms would simply be a one-way ratchet.

In the meantime, residents of almost every borough, council and unitary authority in England continue to experience higher taxes and worse services, year-on-year.

This is the second of three posts on understanding Reform’s success in last week’s Local Elections, why Britain Isn’t Working - and why this is driving people’s search for an alternative, any alternative.

For a more extensive treatment of this, see How Did England Fall Out of Love with Universities? The Four Horsemen of Fees, Culture, Expansion and Quality

I say ‘at least’ because the cohort this analysis was done on entered university over 15 years ago, when the numbers going were far smaller and the graduate premium higher.

This also addresses the last argument of those defenders of mass higher education expansion, that the money spent on HE in some places generates jobs in those towns (always the go-to defence for poorly targeted public spending). Yes, it does, but if we want to support those towns we could also spend that money on *other things* in those towns and those things might actually generate economic benefit.

Its status as a Corporation Sole was described by one senior individual as ‘a carbuncle upon the face of good public governance.’

And no, it is not just correlation. We used to only have that, but we now have an increasing number of causal studies, as he sets out in detail.

I.e. worse.

A rare example of where a Parliamentary amendment that would have delivered this was supported by the Conservatives, Lib Dems, Greens and Reform.

As set out in We need a NICE for education.

Some councils have made herculean efforts to keep some of these going - for example, Hertfordshire, where I live, has not closed a single library. But that is exceptionally challenging and will usually involve difficult decisions elsewhere.

Being imposed in my area from this summer.

As I wrote about in We need a NICE for Education

My epistemic status on this is genuinely uncertain.

There are many ways to regulate. I am aestheticly opposed to "apply for permission, the bureaucracy will get back to you"-type systems.

Here are some other methods to try:

Do you have object-level rules with punishments for breaking them?

Do you have mechanisms where victims get paid damages?

Does the government mediate contract disputes?

Does the government mandate liability insurance?

Does the government have a credentialing system where credentialed people are given licence to use their judgement?

Does the government have a bond system where people who have paid in are given licence to use their judgement?

Does the government give activists objecting to a project the right to be heard?

Does the government give activists objecting to a project the power to obstruct it?

Does the government use taxation or subsidisation as a form of regulation?

Does the government let you avoid procurement process by buying at the London Metals Exchange?

Does the government require detailed reporting of actions taken?

Does the government require external audits?

Does the government have a whistleblowing scheme?

Does the government have a bounty scheme where snitches get riches?

Does the government require annual skills and knowledge training?

Other:

Does the government make you sign an "I am stupid" certificate before taking a certain class of actions?

These methods are not built the same: some preserve liberty, others don't; some are more effective than others; some impose greater compliance costs than others. I would be interested in a NICE for Regulation: what combinations of regulation are most cost effective?

Not de-regululation, but re-regulation: hone in on regulation that works.

One thing that would really help schools struggling to deal with highly needy children would be a statutory definition of when a child can be educated in a 'mainstream setting'

My wife is a deputy head in a primary, and they have some children who require TWO full time adults to manage their needs and behaviour. On what planet is that 'mainstream'? And yet, because of so-called 'parent choice' more and more of these come each year. The funding provided never covers the cost of the provision, and so everyone loses.

Of course, the council loves "parent choice" as it's much cheaper to provide £500 of higher needs funding than provide a £10,000 place in a specialist school. And it doesn't help that those specialist schools are filled not with the most needy children, but with the children of the well off and clued in parents who have armies of solicitors and barristers to make sure they come first in the race for spaces.