How Did England Fall Out of Love with Universities?

The Four Horsemen of Fees, Culture, Expansion and Quality

With repeated news stories of England’s1 universities facing financial crisis and daily news stories criticising them for everything from fraud to left-wing indoctrination - how did we fall so out of love with our universities?

In the piece we’ll explore how a toxic confluence of four issues - high tuition fees, cultural battles, uncontrolled growth and quality concerns - have led to a perfect storm that have, between them, stripped universities of many of their traditional supporters and left them fighting for funds in an increasingly fractious environment.

Have we actually fallen out of love with them?

What do I mean by ‘falling out of love with them’? The Higher Education sector continues to be one of the UK’s biggest export sectors, with four universities in the global top 10 and record numbers of international students wanting to study here. The number of domestic students going to university continues to exceed pre-pandemic levels (though has fallen back from the pandemic peak).

This is a sector with an annual turnover of nearly £45bn, over 2 million students and around 230,000 staff. Doesn’t that trump a few negative headlines?

A defender could also point to the fact that, while public support for universities has fallen, it still remains relatively high. And it’s true: it’s certainly a lot higher than in the US, where it has fallen calamatously, particularly amongst Republicans.

US Confidence in Higher Education

But that would be to ask the wrong question. The question wasn’t, ‘Why do we hate universities?’ but ‘Why have we fallen out of love with them?’ And fallen out of love with them we have. As far back as in 2019 the New Statesmen - hardly a bastion of reactionary right-wing thought - was producing articles such as ‘The Great University Con’, which argued that, “Never before has Britain had so many qualified graduates. And never before have their qualifications amounted to so little. Each year, far from creating graduates of an unparalleled calibre, Britain is producing waves of sub-prime students – students who are nevertheless almost all being highly rated.”

Even aside from the mood music and broader scepticism amongst significant parts of the media and commentators over continued growth, polls now regularly show that a significant number of people think too many people are going to university, or prioritise investment in vocational education and apprenticeships over higher education. Most fundamentally, the government has cut university funding, in real terms, every year for the last decade, such that the frozen £9,250 fee is now worth under £6,000 in real terms - and nor has it made up that investment through grants or other sources.

There’s a well known story about two hikers who meet a bear in the wilderness. As the first pulls on his shoes, the second turns to him and says, ‘What are you doing? You can’t outrun a bear.’2 “I don’t need to,” says the first. “I just have to outrun you.”

In an inverse of this situation, in the race for public funding, it’s not enough for people to like you - they have to like you more than they like every other call upon the public purse. The Conservative Party has made clear that it won’t be changing the funding situation for universities any time soon - and Labour’s speeches about universities have focused on easing the debt burden on graduates and (perhaps) bursaries for poorer students. In the wider education picture they’ve focused on childcare, early years and primary school maths, and skills and apprenticeships - not to mention the pressures either party will surely face, after the next election, on teacher pay and crumbling concrete in schools. Universities are going to be a long way down the list.

Now, there’s a question as to whether the financial crisis facing universities now is quite as bad as some have made out. The number of staff employed has steadily increased over recent years - which does not suggest a sector in fundamental crisis.

Universities have survived so far through sustained, cross-party support for increasing the science and research budget and, most significantly, by increasing the number of international students (who pay higher fees and cross-subsidise everything else) - which has always been a highly fragile dependency that may now be declining after the recent boom years.

There is no doubt that there are pressures, that for some institutions these pressures are acute, and that some difficult choices will be made. But universities have a lot of assets and have just come out of some plentiful years. This is a sector with slowing growth, not one in decline. By my reckoning, at least in the near term, we are looking at efficiencies, consolidation and perhaps contraction - not wholesale collapse.

But regardless of whether we are at the brink or not, continuing to impose real-term cuts year after a year will eventually lead to serious problems - whether that is this year, next year or in 2030. And when both parties show little inclination to keep funding a widely used public service at least in line with inflation, it’s fair to say that we’ve fallen out of love with it.

The question is, why?

The Four Horsemen

We will look at each of the Four Horsemen - Fees, Culture, Expansion and Quality - in turn, before considering their aggregate effect and, briefly what might be done. A few preliminary remarks.

It is not the case that each of the Horsemen is equal in their effects, nor do they work in the same way. Expansion and Quality are closely linked, but Culture is particularly a right-wing concern, and one of the major impacts of fees is to draw off left-wing lobbying from greater funding in favour of fee reduction. There are interactions between four, both in terms of how they are perceived and their real-world effects, but these are not always straightforward.

It is also not the case that any given person - politician, civil servant, journalist or other person with influence - must believe in or be sympathetic to the concerns of all four. Sufficient concern about any one of the Horsemen may be enough for them to deprioritise university funding.

Finally, the purpose of this piece is not to convince you, gentle reader, that each of these issues is necessarily a problem. You may sincerely believe that a fee-funded model is the fairest, most progressive means of funding universities, that further expansion of numbers will boost the economy, or that issues of culture are made up by right-wing politicians - but my hope is that this piece will help you to understand why significant numbers of others disagree, and how the status quo of all factors makes securing additional funding for universities more difficult.

The First Horseman: Fees

And behold a white horse: and he that sat on him had a bow; and a crown was given unto him: and he went forth conquering, and to conquer3.

If a random member of the public was asked to name the most unpopular element of university in the UK they’d almost certainly name fees. There have been repeated large protests about them (often led by the National Union of Students) when they were first introduced by Tony Blair, when they were later tripled by him, and then tripled again by the Coalition, and on various occasions since.

From House of Commons Library, Parliamentary Research Briefing

Almost no-one is going to actively like paying fees, particularly high ones, and while the way the fees are constructed mean no-one has to pay up front - a good thing, which means no-one is barred from Higher Education for financial reasons - this also means people are paying back the loan for a long time, which keeps them in people’s mind (and not in a good way) for a long time. A person who sees £1,000 - £2,000 of their salary vanishing on loan repayments, only to see the balance increase as they’ve not even repaid the interest, is unlikely to be a massive fan of their student loan.

How unpopular are they? Polling typically shows that a fair number of people are happy with students paying some level of fees, and also that support for abolition tends to fall away (to around 1/4 - 1/3 of the population) when people are told how much it would cost. I tend to agree with Nick Hillman of HEPI that they are not terminally unpopular: unless one is the Lib Dems and has broken a high profile pledge, Governments have consistently been able to be re-elected after introducing or increasing fees, and the ‘youth-quake’ of 2017 was overstated, suggesting that even if voters aren’t keen on high fees, few of them prioritise it in voting decisions.

A counter-view to this is that the primary political impact of fees is not in their immediate impact on voting behaviour, but on the long-term effect on graduates. Student loan repayments interact in a toxic way with the cost of living and housing crisis, seeing many young graduates with marginal tax rates of 41% or 51%, or even 77% (if they have children and earn between £50,000 and £60,000). And indeed, this cohort of people in their 30s are not buying houses, having less children - and not switching to the right politically.

But we’re not primarily interested here in the impact of fees on political parties, but on universities. And it’s clear that here, fees are making it significantly less likely for the government to maintain funding in line with inflation - let alone more. This happens for three reasons.

Funding is perceived and handled differently

Funding for most public services is determined through a process called a Spending Review. This is typically conducted every three years4. At this point all the different departments wrangle with the Treasury for some months about how much more money they think they need, and the Treasury tries to argue that they should make efficiency savings (i.e. cuts) in various places to pay for it. Ultimately, the Prime Minister and Chancellor are the final adjudicators as to how much money each department receives and for what - and there is usually large-scale media and political interest into whether core services such as the NHS, police and schools have got an ‘inflation-busting’ rise or otherwise. Funding for science and research - the other big chunk of public funding at universities - is still handled this way, and continues to do well.

Funding universities primarily through fees5 takes university funding out of this process. At its most basic level this makes it easier for politicians to ignore for another year; to put it into the ‘too difficult’ problem. More fundamentally, to increase fees requires a Statutory Instrument to be laid before Parliament and approved by what is known as the ‘affirmative procedure’, meaning that both MPs and Lords have to positively vote for it6. That means a debate in Parliament, with plenty of publicity and the opposition party telling everyone that government is raising fees. Small wonder that the government’s only done this once since they were introduced.

More fundamentally, funding via fees utterly changes the way the public - and the media - view funding increases for universities. Instead of seeing it as ‘public money’, they see it as ‘their money’.7 Funding increases for schools and the NHS are popular; fee rises for universities are unpopular. As a SpAd, I once observed to my principal, only half in jest, that universities were the only public service we could impose real cuts on year, after year, and receive positive headlines for doing so.

Initially, universities welcomed fees. Not only did they receive a major windfall (see graph below)8 but, at a time when many other areas of public spending were seing real cuts in cash terms, being protected from the Spending Review process was seen as positive thing. But as time went on, and public spending returned to normal, it gradually became clear that the fees were a trap - and that it was easier to persuade the Treasury to give inflationary rises to so many public services than it was to persuade the government to raise fees. As someone whose been in and around the sector since 2015, I can remember the original smug pleasure with which fees and the financial security they had brought were spoken of, gradually edging into a degree of anxiety and concern as the freeze continued, before sharpening into real alarm over the last 18 months, in which ‘Vice-chancellors fear UK sector is hurtling into financial crisis’.

Tuition Fees Draw Off Left-Wing Support

For most areas of state spending, with the exception of defence, a major driver for the political left is to increase its budget. Think of the highly effective school funding campaign in 2017, or the many campaigns to get more funding for the NHS - or to increase overseas aid, or free school meals, or benefits. Of course, sometimes people on the right also seek to increase funding but, in general, it is the left that tends to push for more state spending and the right to be more sceptical. This is not meant as a criticism of either side; it’s simply a description.

Of course, more money isn’t the only thing the left campaigns for. They might campaign on specific issues, such as reform of Ofsted, or better working conditions, or equality considerations. But increased funding is typically one of the biggest, if not the biggest, long term focus in any area.

The presence of tuition fees changes that. Instead of campaigning for more funding, a a major part of the left’s energy, commitment and focus is diverted to campaign on fees. Sometimes - as in Corbyn’s two manifestos - this takes the form of fee abolition. At other times - such as Joe Biden’s loan forgiveness policy, or what Labour currently seem to be hinting at - it takes the form of debt forgiveness or other forms of relieving graduate repayments. It is almost never - as a mass cause - a campaign for more university funding.

This throws the normal equilibrium out of joint. The right is still pushing for spending restraint, but the left isn’t on the field. The case for more funding falls only to the sector itself, alongside any technocrats or genuine champions in government they can convince. But without that pressure from campaigners and the left, that becomes a lot harder. Neither politicians nor civil servants are unswayed by popular opinion. If there is a major popular campaign to increase school budgets - or increase childcare - or expand free school meals - but nothing equivalent in the Higher Education space, it is hard not to be led by that (especially as a minister or official may genuinely believe that one of these other budgets has a more worthy case).

In short, the diversion of left-wing campaigning enery to fee abolition and student debt relief is a major factor as to why increasing university funding is so far down the political agenda.

Tuition fees distort the market

Distort the market? But aren’t fees all about ‘marketisation’?

In theory, perhaps, but because HE functions as a Veblen good (as price is seen as an indicator of quality) in practice all courses charge the full fee, regardless of how much they cost to put on. That means that if a provider can put on a cheap course, it can make a surplus on this - and thus providers are incentivised to increase the number of cheaper, surplus-generating courses, regardless of the demand from either the economy or from courses (see stylised graph below: the gap between the blue and orange line represents surplus-generating courses).

The Government does provide a top-up for high-cost subjects - though, unlike the graph shown above, it rarely covers the full cost. And, in practice, universities now make a loss on most courses which they cross-subsidise through international students. But the overall point still holds: universities are clearly incentivised to prioritise the courses on which they make the least loss - rather than those that either the economy needs or that students want. In practice, this has often meant a massive expansion of low quality business and management provision, or provision in the social sciences both of which are popular and cheap to provide9.

This doesn’t directly make people fall out of love with universities - but it does feed into two of the Horsemen discussed below, Expansion and Quality, by increasing the number of (perceived) low value, surplus or unnecessary courses, and concentrating expansion in this area rather than in, for example, engineering.

I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to feed various ideas into the people writing the 2019 Conservative manifesto - and even to have a couple taken forward. One of my pitches that was most definitely not taken forward, however, was the idea that fees should be cut to £3,000 and HE funding switched to a more hybrid fee/grant idea (as I set this out in this article from 2018). As well as there being general opposition to the idea and support for the continuation of the £9,250 fee model, I remember one person, who understood the politics of an election campaign much better than I did, telling me - very politely - that one would have to be an idiot to deliberately raise the salience of an idea the Opposition was strong on by setting out a weaker offer than their highly popular policy. They were undoubtedly right - at least about the politics.

But the broader case for a more hybrid system remains strong.

The Second Horseman: Culture

And there went out another horse that was red: and power was given to him that sat thereon to take peace from the earth, and that they should kill one another: and there was given unto him a great sword.

The so-called ‘culture wars’ are now a regular feature of the narrative around universities, with regular reporting of a university renaming a building, cancelling a speaker or adding ‘trigger warnings’ to classic texts. Particular flashpoints have included free speech, trans rights and the gender critical movement10, ‘decolonisating the curriculum’ and critical race theory, and a host of other, related matters. Ministers have at times weighed in, sometimes through rhetoric, at others through more substantive measures such as the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act.

This is a relatively new phenomenon. As recently a decade ago, the Coalition was putting out glowing documents that celebrated not only the economic impacts of universities, but claiming that attending university led to ‘less crime, greater cohesion, social trust and tolerance.’

So what happened? Two things.

The first, and least important, is Brexit, which shot cultural matters to the fore across the whole of British society, and revealed new political fault lines in society aligned across cultural and educational lines, rather than economic or class. Universities, graduates and students overwhelmingly supported Remain - and suddenly, that ‘increased social trust and tolerance’ might start being interpreted as ‘supports the EU and high immigration’.

The more significant issue, however, is the rise over the last decade of identitarianism upon the left; the so-called ‘Great Awokening’, in which matters of gender, race and other identity matters surged in importance and broke into the consciousness of mainstream society and activism in a host of different ways. A few people still like to say ‘woke is a meaningless term’, but while I agree it can be used meaninglessly, there is nevertheless a real shift that has happened here on the left. You’ve probably read descriptions from the right, so I’m sharing here the (unpaywalled) description that I’ve seen praised most often by people on the left, written by James O’Malley.

Identitarianism represents a genuine shift of attitudes and policy prescriptions from classical liberalism or old-school leftism - and as well as being widely criticised from the right, has also been critiqued by figures from the left, such as in The Identity Trap, by Yascha Mounk. It is, of course, not unique to universities - but it is particularly strong there. You may think this is positive or you may not; you may simply think that whatever is happening should be less important to ministers than fees, funding, teaching and scientific research - but you should acknowledge that universities are now doing things differently. The ‘anti-racist’ ideas of Kendi, Eddo-Lodge and Andrews were simply not mainstream 10-15 years ago; trans rights were not a major political debate; universities were not ‘decolonising their curriculum.’ In 2002, Labour Cabinet Minister Mo Mowlam11 nominated Churchill as the greatest ever Briton in a national poll, which he won - and this was considered completely unremarkable.

One common misconception in the university sector - often reflected in headlines or commentary, and borne out through private conversations - is that when Ministers raise these issues, or bring forward laws or guidance to try to counter them, that they are just trying to win votes or to ‘play to their base’12. This in turn can lead to the dangerous assumption by the sector that there is no cost to embracing identitarian policies - beyond perhaps a few headlines in the Daily Mail - and that it is a cost-free option, perhaps to appease staff members or students13.

This is a serious mistake. I’m not saying that Ministers never play to their base, but while not everyone on the right cares about these matters, a significant number genuinely do. Culture may not be as significant a horseman as Fees and Expansion - but the fact that universities have embraced this ideology so thoroughly has done them harm.

I would crudely divide those with concerns into three categories:

True believers - who have thought deeply about identitarianism and oppose it on a fundamental level.

Traditionalists - who oppose the traducing of traditional British history, heroes and culture.

Efficiency fiends - who believe it shows universities are fat with cash.

True believers

These are people who have looked at what is happening in universities (and elsewhere) on the shift to the identitarian left, who have often read the books and articles on intersectionality, critical race theory and gender and those that critique them, who have seen the motte and bailey arguments play out time and again - and who thoroughly reject and oppose it. They have a higher likelihood of being classical liberals (whether originally from a right or left background) and to be genuinely committed to issues such as freedom of speech and association14. Just like any group of people who take this level of interest in a political ideology, they are pretty rare in the population, but unduly concentrated amongst those highly active in politics and public policy.

People in this camp tend to genuinely believe that cancel culture, critical theory and other elements associated with ‘equity, diversity and inclusion’ are worsening racial tensions and increasing polarisation, whilst being a direct threat to meritocracy, freedom of speech and tolerance. When I worked in Government and we were just beginning work on the Free Speech Bill, one very senior person15 said to me, “All the very worst ideas that are tearing our society seem to be coming out of universities - we have to do something about this.”

One of the most cogent accounts of this was recently written by Bill Ackman, following a major escalation on this subject in the US after three Ivy League university leaders were unable to clearly denounce people calling for genocide (two have since resigned)16. He writes about how ‘Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion was not what I had naively thought these words meant.’:

Under DEI, one’s degree of oppression is determined based upon where one resides on a so-called intersectional pyramid of oppression where whites, Jews, and Asians are deemed oppressors, and a subset of people of color, LGBTQ people, and/or women are deemed to be oppressed. Under this ideology which is the philosophical underpinning of DEI as advanced by Ibram X. Kendi and others, one is either an anti-racist or a racist. There is no such thing as being “not racist.”

Under DEI’s ideology, any policy, program, educational system, economic system, grading system, admission policy, (and even climate change due its disparate impact on geographies and the people that live there), etc. that leads to unequal outcomes among people of different skin colors is deemed racist.

As a result, according to DEI, capitalism is racist, Advanced Placement exams are racist, IQ tests are racist, corporations are racist, or in other words, any merit-based program, system, or organization which has or generates outcomes for different races that are at variance with the proportion these different races represent in the population at large is by definition racist under DEI’s ideology.

…

The techniques that DEI has used to squelch the opposition are found in the Red Scares and McCarthyism of decades past. If you challenge DEI, “justice” will be swift, and you may find yourself unemployed, shunned by colleagues, cancelled, and/or you will otherwise put your career and acceptance in society at risk.

The DEI movement has also taken control of speech. Certain speech is no longer permitted. So-called “microaggressions” are treated like hate speech. “Trigger warnings” are required to protect students. “Safe spaces” are necessary to protect students from the trauma inflicted by words that are challenging to the students’ newly-acquired world views. Campus speakers and faculty with unapproved views are shouted down, shunned, and cancelled.

…

The psychologist, Professor Jonathan Haidt, has also weighed in. In a piece titled Why Antisemitism Sprouted so Quickly on Campus, he argues that the new morality that underlies identitarian (i.e. ‘woke’) reforms directly increases the propensity for identity-based hate:

The new morality driving these reforms was antithetical to the traditional virtues of academic life: truthfulness, free inquiry, persuasion via reasoned argument, equal opportunity, judgment by merit, and the pursuit of excellence. A subset of students had learned this new morality in some of their courses, which trained them to view everyone as either an oppressor or a victim. Students were taught to use identity as the primary lens through which everything is to be understood, not just in their coursework but in their personal and political lives. When students are taught to use a single lens for everything, we noted, their education is harming them, rather than improving their ability to think critically.

…

The central portion of the chapter describes two different kinds of identity politics, one of which is good because it actually achieves what it says it is trying to achieve, and because it brings both justice and, eventually, better relationships within the group. We called this “common humanity identity politics.” It’s what Martin Luther King, Jr., and Nelson Mandela did by humanizing their opponents and drawing larger circles that appealed to shared histories and identities. The other form we called “common enemy identity politics.” It teaches students to develop the oppressor/victim mindset and then change their societies by uniting disparate constituencies against a specific group of oppressors. This mindset spreads easily and rapidly because human minds evolved for tribalism. The mindset is hyper-activated on social media platforms that reward simple, moralistic, and sensational content with rapid sharing and high visibility.5 This mindset has long been evident in antisemitism emanating from the far right. In recent years it is increasingly driving antisemitism on the left, too.

Common enemy identity politics is arguably the worst way of thinking one could possibly teach to young people in a multi-ethnic democracy such as the United States. It is, of course, the ideological drive behind most genocides. On a more mundane level, it can in theory be used to create group cohesion on teams and in organizations, and yet the current academic version of it plunges organizations into eternal conflict and dysfunction. As long as this way of thinking is taught anywhere on campus, identity-based hatred will find fertile ground.

For true believers, opposition to the most (perceived) harmful forms of identitarianism, ‘wokeness’ is as moral and important a cause as the ‘DEI’ initiatives themselves as for those who advocate them. Most still recognise the vital roles of universities in education and scientific research - but the ideological trends trouble them greatly.

Traditionalists

In contrast to the true believers, traditionalists have a much simpler objection. They are people who are proud of British history, its statues, its literature and its traditions - and strongly dislike it when established institutions, heavily funded by the taxpayer, traduce them.

Most understand there have always been radical students and Marxist academics - but are much more likely to upset when the establish and authorities of major institutions seem to go along with what they see as nonsense (and offensive nonsense at that), whether it is renaming halls named after Gladstone, ‘decolonising’ Nelson and Drake or adding trigger warnings to Shakespeare.

Most traditionalists don’t spend too much time thinking about this. They’re not going to go on a crusade against universities - but the knowledge that universities are acting this way makes it less likely they’re going to step up and actively support them.

Efficiency fiends

Efficiency fiends may or may not care about wokeness, but what they do care is about efficiency and getting value for money for taxpayers. For them, the fact that universities are busy decolonising curricula, establishing slavery commissions and appointing highly paid senior roles in diversity and social value is a clear sign that universities don’t need more money.

This is sometimes frustrating to university leaders, who point out that this only costs a couple of million, and they have an annual turnover in the hundreds of millions. But what the sector leaders fail to recognise is that efficiency fiends have often worked in the private sector, where the bottom line is king, and where private companies routinely have to deal with a year-on-year drop in turnover of 10%. Private sector enterprises that genuinely had their back to the wall simply wouldn’t do this sort of thing - and the fact that universities are sends a message to many that they are simply not as hard up as they like to say.

Overall, the debates over Culture do several things. They make some people more hostile to universities - or at least less inclined to step forward and actively support, and in the no-quarters bear-race for public funding, that alone can often be fatal to a case. They divert attention from other matters. And they weaken the case that universities genuinely need more support.

One comfort to the sector is that, if Labour win the next election, this will become less of an issue. That is undoubtedly true, but a potential worry is that, in opposition - freed of the need to worry too much about the nuts and bolts of running the system - the Conservatives could become significantly more hostile, in the way of the Republicans in the US. That would have severely negative consequences for universities in the medium term.

The Third Horseman: Expansion

And I beheld, and lo a black horse; and he that sat on him had a pair of balances in his hand. And I heard a voice in the midst of the four beasts say, A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny; and see thou hurt not the oil and the wine.

Rows about how many people should go to university go back decades - with the most recent touchpoint Tony Blair’s famous pledge that 50% should go17 (a milestone that was reached a couple of years ago). Most recently, the current Prime Minister referred to that target as, “one of the great mistakes of the last 30 years”, leading to “thousands of young people being ripped off” in a speech at the Conservative Party Conference.

I do not intend to relitigate this battle now, though I will touch on some of the high points on each side. A major transformation in the debate occurred in the Coalition years; both, interestingly, initiated by the same Minister, David (now Lord) Willetts. The first of these was the removal of any form of number controls18 , which had existed for the previous three decades. This led not only to faster expansion, but also meant that - regardless of what Ministers said they wanted - they had no power to control the numbers going, nor to which institutions, nor on which courses19. The second was the development of the Longitudinal Educational Outcomes (LEO) dataset, an impressively rich dataset that has transformed our understanding of the economic returns to university, thanks to some detailed studies which show how much different courses - and universities - boost lifetime earnings (after controlling for sex, prior academic ability and many other factors).

Principal arguments against expansion include the fact that one in five graduates (15% of women, 25% of men) would have been better off had they not gone to university, and the fact that the graduate premium has been steadily declining.

There is also the fact that over a third (36%) of graduates are in non-graduate jobs, suggesting we don’t need nearly as many as we produce20. Many people would go further, and argue this proportion is actually far higher, as many of the jobs we now class as ‘graduate jobs’ do not need to be done by graduates. Paramedics, social workers, journalists, police-officers and even bankers often used to enter the workforce without a degree, either at 18 or after some training in a local college, but now are becoming - either as a direct requirement or simply by a changing norm - increasingly dominated by graduates.

As education is a positional good, and can demonstrate certain skills to employers21, it is entirely possible that even if a degree added no value at all, employers might choose to preferentially recruit graduates over non-graduates. This specific case of signalling is in fact literally a classic economics result, typically taught in introductory economics courses. In such a situation, there would still be a graduate premium, it would still be in the interests of individuals to go to university and for employers to recruit graduates - but there would be absolutely no benefit to the country at all. This is clearly not the case for all university courses - but it may well be the case at the current margin.

A majorconcern is that the major increase in participation over the last 15 years has shown no noticeable increase in UK growth or productivity. I know of one study that seeks to argue that it does, but this study begs the question22: it assumes that having a degree adds a certain ‘quality’ value to each unit of labour, and then proceeds to claim that more graduates mean that the labour contribution to productivity has increased. Highly suspiciously, the study then needs to make Total Factor Productivity (TFP) go negative over this period (something highly unusual for a developed economy not in recession) to make the sums add up. A more parsimonious explanation would be that TFP remained positive but the productivity returns to a marginal degree declined.

One important factor here is that when the economy had weak demand and (relatively) high unemployment, such as shortly after the 2008 financial crisis, expanding the number of people in university didn’t matter much. It took young people out of the (weak) labour market and the spending helped to stimulate the economy. In that sort of economic environment, you can stimulate the economy by paying people to dig ditches and fill them in again.

But in today’s economy, the situation is very different. Demand is high, employment is high, debt is high and the concerns are overstimulation and inflation. In this situation, spending on unnecessary degrees represents a genuine opportunity cost: that money could be better spent on transport infrastructure, or social housing, or renewables, or cutting the deficit. Taking people out of the labour market has real costs, too - it’s no longer a helpful way of keeping down unemployment, but a genuine cost to increasing productivity and growth.

Clearly, some people disagree with this analysis, and as the Chief Executive of Universities UK wrote an article to that effect yesterday, the fairest approach here is to link to it. To briefly set out why I think this doesn’t persuade:

There is too much reliance on the fact that university benefits the average graduate. Yes, it does, but it is the marginal graduate that matters, when we are considering whether to expand or contract.

Other countries such as Germany, Switzerland and Canada educate more people to higher technical level (think advanced FE college level) and do very well. It is not clear more degrees are the answer.

The signalling argument set out above, and the fact that many jobs that currently ask for degrees could be - and historically were - taught on the job, or in a local college.

We clearly won’t resolve these disagreements today. You may continue to be convinced by Vivienne Stern, rather than by me. But in terms of this post, I trust that you will see that concerns about the third Horseman are serious, widespread and reflect a detailed - if contested - engagement with the evidence, not some knee-jerk reaction to an old New Labour speech.

Stepping back

Regardless of which side one comes down on regarding expansion, two things should be uncontroversial.

The first is that, given a large number of people sincerely believe that too many are people are going to university, on low value courses - and that this includes a decent number of people in Government - these people are going to be hard to convince to fund universities more, and are going to support measures that either reduce funding, or otherwise crack down on what is seen as low value, or low quality, revision.

The second is that, if there is only so much money that the government is going to spend on universities, prioritising expansion means spreading the butter more thinly. This is particularly the case if, as now, the number of 18 year olds is increasing so that even if the participation rate stays the same, student numbers - and thus government spending - increases.

Imagine if, in a given year, a government was willing to spend X additional pounds on universities. One might choose to spend that on three things: (a) increasing the number of student places; (b) increasing the funding per student, either for all courses, or perhaps for more expensive courses; (c) increasing the amount of student support (maintenance loans and/or grant). A reasonable person might think that there would be a conversation between the Education Secretary and the Chancellor, informed by conversations with universities and perhaps the NUS, as to how to split the funds available between the three priorities.

With no management of numbers - the current situation - there is no ability to have that conversation. Expansion is prioritised - and if the expansion is more than the Government wishes to fund, it controls the cost by squeezing the funding per student, and the amount of maintenance support. And that is precisely what has happened, with the funding per student (real value of fees + grant) falling steadily over the last decade, maintenance grants abolished, and even the maintenance loan falling well behind inflation.

Real value of Maximum Maintenance Loan - chart produced by the Russell Group

Even if one supports expansion, one should still support managing the number of student places - in order to ensure expansion takes place at a rate that they can be properly funding.

The Fourth Horseman: Quality

And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.

Quality is Expansion’s little cousin, so should probably not be represented by the greatest of the horsemen. But while they are closely related - most people link the expansion of courses to too many low quality, or poor value courses - they are not identical. I know a number of people in the policy space who support expansion while genuinely recognising the need to take action against poor quality courses.

The removal of number controls did not create a price-differentiated market, but it did create a market. Many of the Russell Group responded by expanding, recruiting more students. So far, so good. But the effect at the other end of the sector was to create a race to the bottom. Desperate for students to keep afloat, and devoid of any serious quality regulation (see below), there was nothing to stop many universities lowering standards - in who they took, what was provided, or the standards required to graduate.

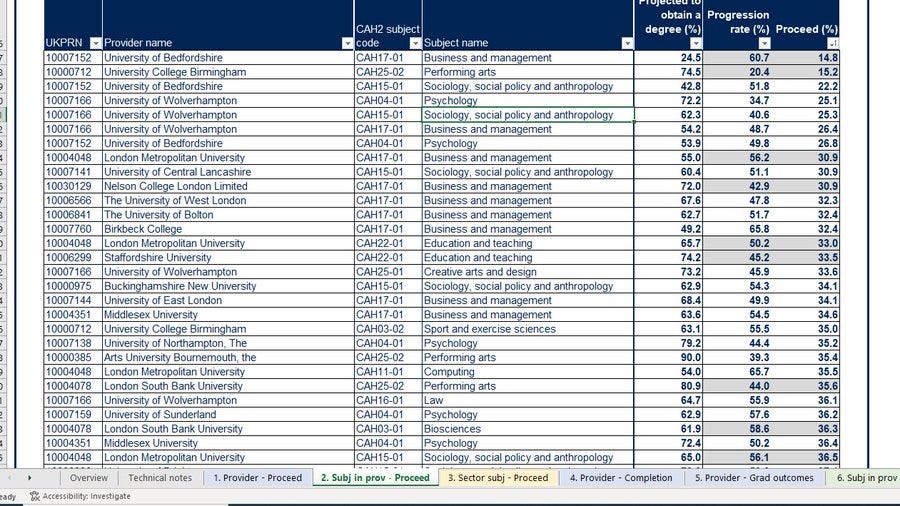

Frequently quality concerns are expressed in terms of outcomes, particularly drop-out rates and progression to highly skilled employment or further study - both of which are astonishingly bad on some courses. The table below is taken from the Office for Students’ ‘Proceed’ Data.

Other concerns centre around the low academic quality of some courses - citing, perhaps, the fact that 7% of graduates in England graduate without basic skills (Yr 9 level) in English and maths, the low level of qualifications of students admitted on to some courses, or the fact that universities have openly admitted to lowering basic literacy standards on arts degrees for students from certain backgrounds. Contact time used to be a major cause for concern, though this seems to have fallen out of fashion in recent years.

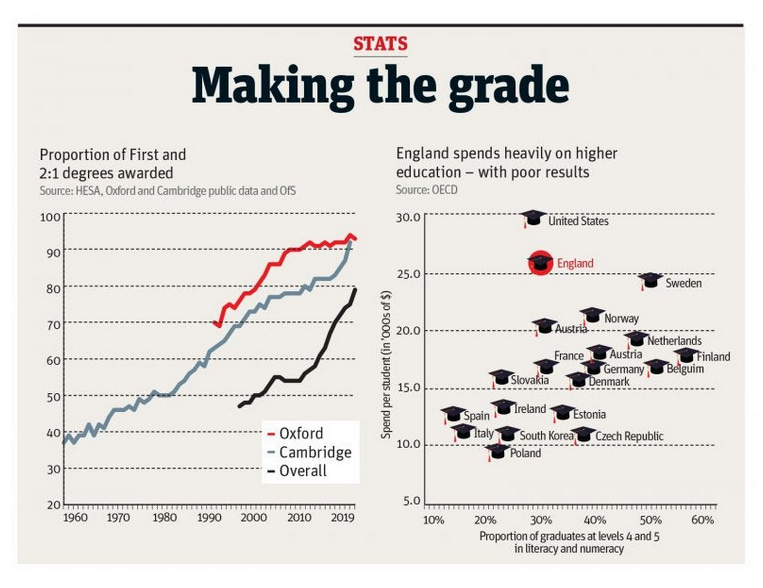

Grade inflation is also a major issue for those concerned about quality, with over 32% of students now getting a First Class degree, compared to just 15% in 2010. The number of degrees at 2:1 or First has almost doubled, from just over 40% in 2000 to over 80% today. Given this has coincided with a massive expansion in the number of people going to university - and no noticeably increase in the skills of graduates - this is a clear quality concern.

Graphs below from the New Statesman

Winning every battle but losing the war

I sometimes underappreciate the fact that I applied to university during the rare window in which there was an objective, albeit imperfect, public assessment of the quality of university teaching. Subject Assessment rated each discipline, at each university, out of 4 for six different factors, giving a total out of 24.

Subject Assessment was discontinued in the noughties after lobbying from universities, and nothing similar has existed since.

Unlike every other form of mass public service, universities lack a robust form of quality assessment. Schools have Ofsted, hospitals have the Care and Quality Commission, police forces have His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. Universities have the Office for Students, which has completed under a score of investigations in five years (compared to well over 20,000 by Ofsted). Neither the OfS nor the QAA which held the quality role before it has ever found a significant failing against a university that was comparable to an Ofsted ‘Requires Improvement’ or ‘Inadequate’ - nor are there any similar consequences23.

And this matters, because universities have huge autonomy. They, and they alone, determine their curriculum, set the standards for their degrees and decide what proportion of students get a First. They choose which students to admit, and with what qualifications. There are good reasons for this autonomy - it underpins the strength of our world-class institutions - but it causes significant problems at the bottom end.

Matters are better in highly regulated degrees, such as nursing or engineering, where professional bodies maintain more robust minimum standards.

It was sector lobbying that caused Subject Assessment to be abolished. Since 2015, I’ve worked directly on two major drives to strengthen quality in universities, and neither have worked.

The first, the TEF, was implemented, but was neutered due to the fee-link being abolished, meaning there are no longer tangible benefits for doing well (or costs for failure). I still think the TEF has value, both reputationally in terms of providing information to students, and in helping to focus university minds upon good teaching and postive outcomes, but it is a shadow of what was initially intended.

The second, on which I worked between 2019 and 2022, involved a significant strengthening of the OfS’s quality function. This involved the introduction of a new ‘B3’ condition relating to a minimum threshold for drop-out rates and graduate outcomes, ‘boots on the ground’ investigations for courses of concern and a broader drive to move quality further up the regulators. As with the TEF, this has not done nothing - investigations recently found cause for concern in business studies provision at two universities - but it has hardly been transformative. Only a handful of courses have been investigated to date, no fines (or other punitive regulatory actions) issued, no courses closed or had recruitment frozen. The fact that one of the investigations was unable to find problems at a university with some of the worse outcomes in the land is also concerning.

The method by which universities regulate themselves - external examiners, light-touch subject benchmarks - was fit for an age in which there were a couple of dozen universities and a gentleman’s agreement was sufficient to keep standards high. It is not suitable for a mass public service, with a far more diverse student base and range of providers, funded by billions of pounds of taxpayers’ funding.

While much provision in the sector remains strong, the simple truth is that one cannot have confidence that a 2:1 from an English university is a genuine mark of quality - or that every course is worth the £9,250 that students pay to attend.

In conclusion

If this looks bleak, that’s because it is. Concerns about the current state of universities are deep-seated, wide-ranging and come from a range of political perspectives. They have not only a broad base of public sympathy to tap into, but are held by people who have reached them after looking deeply at the evidence24. Too many of the responses by the sector come down to, ‘We need to shout about the good things we do more.’ Well, I’m sorry, but that won’t cut the mustard.

There’s a well known evangelical apologetic about the necessity of grace25, to explain why people who aren’t mostly good can’t get to heaven by themselves. Imagine, it goes, that you’ve been given a nice glass of refreshing milk to drink. Lovely. Now imagine that only 60% of the glass is full of milk, and the other 40% contains slurry. Do you still want to drink it? It’s mainly milk, after all. No? How about 80% milk, 20% slurry? 10% slurry? Still no? So now you see why it has to be all good, not just mostly good.

As with the milk, so with universities. No-one disputes that Cambridge provides an outstanding education26. Or Imperial, UCL and King’s. Most people familiar with the sector would agree that Derby and Northumbria are putting on some great vocational courses. And of course, there’s lots of fantastic research - vaccines, Nobel Prizes and so on. But that’s not the point. If 20% - or 25% - or 30% - of the provision is seen as no good, and not worth the money, then people aren’t going to want to fund it. And under the current system, there’s no way to either differentially fund, or preferentially increase places, at the higher quality institutions and courses. The strength of the University lobby has been sufficient to block robust quality regulation, block number controls and block minimum entry requirements - but not strong enough to increase funding or win broader support.

Of course in real life, unlike in the apologetic, there is some level of slurry which would be acceptable. No-one could detect a single molecule - or even a million molecules. And any mass public service will have some elements that aren’t up to scratch. But the current status quo ain’t it.

Amongst the bleakness, there are two rays of hope. Firstly, that we remain much less polarised, and much more positive, about our universities than the US. And the second is that the science and research part of universities provides a model for success. Unlike the teaching side, this continues to enjoy deep, cross-party support, was protected (in cash terms) from austerity and has received a significant budget uplift over the last five years. There are perhaps two principal reasons for this: (a) that the economic returns are uncontested and strongly understood; and (b) that the funding mechanism - both through grant allocation and the so-called ‘Quality Related’ block grant - strongly rewards quality, so that government can be confident that funding is going towards positive outcomes.27

For teaching to regain that status will take some fairly major shifts. Perhaps the most promising - though difficult to reach from the current situation - would involve addressing the two most damaging of the Horsemen; that is Fees and Expansion. This could involve reverting to a more hybrid funding system of fees and grant, and the reintroduction of proper numbers management; the savings from preventing uncontrolled growth could then be recycled into a proper funding uplift per student, and a more generous maintenance loan and/or grant for the poorest students. The sector would then have to make its case for further expansion - or funding uplifts - just like any other public service.

Alternatively, real control on quality could restore confidence in the sector. This would need to involve central oversight of standards and grade inflation, a serious inspection regime - like Ofsted, or the CQC in Health - with proper site visits, rigorous holding to account on completion metrics and outcomes - and, most fundamentally, real consequences for failure. If a school fails its Ofsted - and they do, all the time - the head is likely to sacked, and the school brought into an academy trust. Imposing this sort of accountability regime on universities would have serious downsides in terms of institutional autonomy - and potentially the long-term future of our best universities - but it might just restore public confidence.

My own preference would be the first option. Our best universities are outstanding - and they are not only those at the top of the league table, but excellent provision right across the country. But there is too much poor provision, and the evidence that investment in more graduates - as opposed to more transport infrastructure, or renewable energy, or skills - is the priority for our country now is week. There may be some third way, not discussed here. But one way or the other, we need to find a long-term solution to solve the funding crisis and bring universities back into favour.

Education in the UK is devolved, which means that Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have autonomy over their own systems. Everything is far from hunky-dory there, too, with Scotland recently announcing a 5.9% cash cut for universities, but the issues are very different - and in this piece we’ll be focusing on England.

I never actually picture bears running that fast, but it turns out they can reach up to 35mph. Come for the university discourse; stay for the bear facts.

The association of these factors with the Biblical horsemen is the most dubious part of this post, was done largely for aesthetic reasons, and should probably be ignored, but Fees has conquered all other factors in its domination of the discourse; Culture is frequently referred to as a ‘culture war’; Expansion has led to a Malthusian crisis, i.e. famine; and a lack of Quality results in the removal of any point - i.e. the death - of education. If you think this is tenuous, that’s because it is.

Though there were a series of one year Spending Reviews in the period around 2019 and 2020 due to the political turmoil and impact of Covid.

Approximately £1.6bn is funded via direct grants, which are still handled through the Spending Review process. This compares to around a £20bn outlay on tuition fees and maintenance support loans.

Originally, to raise fees by inflation or less only required the ‘negative procedure’, which often wouldn’t require a debate. However, in the ‘wash-up’ process for the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 - precipitated when Theresa May called the snap general election - one of the concessions extracted by Labour was that any rise in fees would require the affirmative procedure. I remember this being welcomed by (at least some) universities at the time, as it made it harder to operationalise the proposed fee-link in the Teaching Excellence Framework, but in terms of the long-term impact on university finances it was something of a Pyrhhic victory.

Many on the right might wish that the public saw more public funding this way!

A large part of this was because the policy on £9,000 fees had assumed that we would see a genuine price-differentiated markets, where most universities would only charge £6,000 or £7,000 and only the most prestigious would charge £9,000. I’ve spoken to several people involved in the process - on the political and civil servant side - and am confident this was a genuinely held belief by most of those working on the policy. In the real world, it turns out that Higher Education is a Veblen good, and almost every university put their fees up to £9,000 and kept them there.

There is clearly also high quality provision in both these subjects.

Not to be confused with Mo Farah.

The people who think it is all about votes make the fatal mistake of assuming that their adversaries are not just mistaken, but stupid. Particularly in a cost of living crisis, only a minority of voters prioritise these sorts of campus cultural matters (immigration, now, is another matter) - and you can be sure that Conservatives know this as well as you do. Most Conservatives act on these matters because they care about them, not because they can’t understand basic electoral politics. Always do those you disagree with the credit of assuming they are acting rationally on their own terms.

As one Vice-Chancellor said to me recently, “There are some tensions but our culture isn't as fractured as the US and, with a tiny tiny number of exceptions, the leadership isn't woke.” I agree with him - very few VCs in my experience, are ‘woke’. But what too many have done is to turn a blind eye while enabling or empowering activist groups, staff networks or HR/Diversity directors to implement some very radical policies, not realising (sometimes until to late) the potential costs.

And, fortunately for the university sector, institutional autonomy. Some of the most committed people in this category I worked with in government have a genuine belief in institutional autonomy as essential to scientific endeavour and intellectual flourishing. That’s one reason why we’ve had a Free Speech Bill rather than attempts to shut down courses or dictate curriculum.

Not someone in DfE or who I ever worked for directly, so there is no way to work out who it is.

England’s university leaders have, on the whole, handled this particular situation much better than those in the US have done.

Technically speaking, that 50% should attend some form of tertiary education, but typyically interpreted and quoted as university.

With the exception of a very small number of courses, such as medicine.

Following a consultation, the government recently resiled from a potential attempt to reintroduce number controls.

There is a hackneyed argument that observes that some graduates may, through choice, take a non-graduate job because they realise they love it, or are working for a charity. Sure - but 36%? One need only compare the radically different proportions of graduates in graduate jobs from the same subject at different universities to see the fallacy of this argument.

Such as some level of academic intelligence, and the ability to stick to something for three years.

In the correct sense of the phrase.

In theory, the OfS has far-reaching powers, but these have never been used.

This is not to say that other people have not looked at the evidence and reached different conclusions.

For given values of well known.

As does Hull.

Research England is currently doing its best to undermine this, by proposing that an additional 10%, for a total of 25%, of the £2bn Quality Related research funding it allocates each year should be switched from funding outstanding research outputs to rewarding ‘people, culture and environment’, which is likely to be based on a range of factors including ‘EDI data’ - and, no doubt, management box-ticking and other flim-flam. Not only would this be bad in itself, promoting bureaucracy and perverse behaviours, the most serious potential outcome is the likelihood of fundamentally undermining the cross-political consensus that research funding is being directed towards the highest standards of excellence, rather than in the service of contested political aims. Fortunately, Research England has since indicated it may be reviewing this change in weighting back on this - it would be very wise to do so. The best critique of this dangerous proposal I’ve read is by former Vice-Chancellor of Warwick, Sir Nigel Thrift, and can be found here.

1) Speaking from my own discipline — Architecture — the expansion has been most damaging for the notionally 'elite' universities. When I started teaching in London, the sector had some small, highly prestigious institutions (UCL Bartlett, RCA etc) and a lot of large ex-poly courses. The former were very hard to get into, had low SSR and were intense. A decent degree from one was a strong signal of quality, and everyone on the courses was very ambitious and driven.

The latter were large, and had a bit of sink or swim ethic, at least in first year. Lots of people would fail or drop out. But the teaching was still good if you engaged with it, and graduates were generally very employable and often did well.

I've taught at a bunch of places across both groups. Since the cap on numbers was removed, all the prestigious places have got massive (2-4x larger cohorts). The academic culture and rigour has been diluted, and the quality is no longer in any way dependable. At the same time, most of the ex polys have shrunk away — in size, they're half as big or less. In neither case are you allowed to fail anyone any more because of league tables (and now B3 — thanks for that!) so you're nursing students through these courses who should have dropped out and done something else. Every metric creates its own monsters -- graduate unemployability reflects the fact that a lot of people who make it through should not have done.

2) TEF is a waste of time because the metrics are all the same ones the League tables use. So institutions are all already massively overfitted for producing these, regardless of the quality of the courses. They know how to game them. Everyone has their NSS maximisation strategy. Most of what you're measuring is how good they are at gaming.

The deficiencies of NSS as a measurement of teaching quality are obvious — to use an analogy, it's like a restaurant review by a person who's only ever been to one restaurant. No baseline. GOS mostly measures how good the university is at phone banking. It's all miles away from actual 'quality.' I've seen very poor courses with great NSS, and vice versa.

3) My suggestion for a quality measurement would be for the OfS to just sometimes show up and sit in at External Examination. Universities are meant to manage their own quality assurance. But the temptation is always for this to become friends doing favours for each other. No one is very incentivised to rock the boat. You wouldn't have to do this for very many courses — say one per institution per year, without prior notification. It would have a big effect.

I was a QAA reviewer back in the day, and it was an awful process that ate up huge amounts of money, time and effort for very little return, with unis rapidly learning to game the system. I can't imagine that a uni OFSTED would be any better. It's prescriptions also contributed, I think, to the rise in grades, but not by improving teaching.