Britain isn't working (Part 3 of 3)

Understanding the rise of Reform

The third of three pieces this week on understanding Reform’s success in last week’s Local Elections, why Britain Isn’t Working - and why this is driving people’s search for an alternative, any alternative. Part One and Part Two can be found at the links.

In the first of this series we looked at how the classic relationship between tax and public services has broken down, with the tax take increasing but public services getting worse. We saw that people feel this across almost every area of life, from the NHS to crime to bin collection - as well as many feeling more ‘cultural’ concerns going ignored, particularly on immigration and small boats.

People are searching for an alternative - any alternative. They voted for Brexit in 2016 (and again in 2019), searched for it in Labour in 2024, and are now turning against both the main parties. This isn’t because Reform has a detailed policy platform they like - it doesn’t - but because they are angry and upset, they are crying out for change - and having been repeatedly let down, they are willing to try one more thing.

We looked at how the reason for the decline isn’t solely due to demographic change or Baumol’s cost disease, but because both parties have, in practice, cleaved to a core set of pro-Boomer and pro-Anywhere policies that have collectively immiserated the country.

In Part One we saw that:

Long-term failure to build enough homes has priced a generation out of ownership, sent rent costs spiralling and broken the social contract between hard work and home ownership.

Mass low-skilled immigration directly decreases GDP per capita, as well as putting (more) pressure on house prices, depresssing wages and weakening social cohesion.

The numbers on out-of-work benefits is soaring, with mental health a major component of this. This is a direct cost and also takes people out of the workforce who could be paying tax. Labour’s reforms only make the bill rise more slowly.

The UK has some of the highest energy costs in the western world. This increases the cost of living for households, increases costs for business and deters companies from investing. The issue is less subsidising renewables, but more failing to maintain oil, gas and nuclear through the transition.

Then in Part Two we looked at how:

Uncontrolled university expansion had ceased delivering positive marginal returns and was now a net cost - in addition to leaving a generation of young missold a dream to receive only a lifetime of debt.

The inexorable increase in regulation, year-on-year - in both the private and public sector - is dragging the economy down, making goods and services more expensive and causing every penny in tax to go less far.

A failure to confront the large increase in mental health and special educational needs, or to re-examine the causes and incentives in the system, is leading to increasingly greater costs, both financially and for those affected.

Local authority budgets are increasingly spent on social care and special educational needs, while other areas have faced large cuts. This means people see local amenities and services getting steadily - while council tax goes up every year.

Here in Part Two we’ll look at the last four of these policies:

Not building enough homes

Addiction to mass immigration - and failing to control the border

Permitting the numbers on out-of-work benefits to soar

Tolerating and exacerbating high energy costs

Uncontrolled university expansion

The spiralling cost of regulation

Not facing up to the rise in mental health and special educational needs.

Hollowing out Local Authority budgets

Encouraging the growth of radical identity politics

Failing to resource the criminal justice system

A maximalist commitment to human rights law

Maintaining the state pension triple-lock.

Encouraging the growth of radical identity politics

From the ‘Great Awokening’ to Black Lives Matters, from the rise of trans to ‘decolonising’ the curriculum, the great social debates over identity politics, have become increasingly prevalent over the last 10-15 years. ‘Woke’ is a new ideology,1 at least in the mainstream, and one with significant differences to older forms of left-wing and progressive thought - and both its proponents and detractors should be willing to admit this.

Both the Conservatives and Labour have encouraged, or at the least permitted, this to become embedded across the whole of the public realm, from mandating the teaching of Relationships and Sex Education in schools (in a way which opened the floodgates to radical teaching), to the Public Sector Equality Duty - and, simply, by not putting their foot down firmly when the civil service, councils, the NHS, police forces, state funded museums and universities adopted wholesale radical new stances on race and gender. Yes, some Conservative Ministers made speeches about it and a small number2 actually did something about it, but most did not. The public doesn’t distinguish between Ministers and the public services provided by the state: just as the Health Secretary gets the blame if the NHS isn’t working, so too with woke.

Identity politics is not without its direct costs, as Pamela Dow’s outstanding piece on the HR-ification of the British economy also makes clear. The residents of Birmingham, currently facing swingeing cuts as the result of their council being bankrupted by an absurd ‘equal pay’ claim could no doubt tell you more,3 and there are almost certainly indirect but substantial costs to productivity from so many managers and senior executives - particularly in the public sector - focusing on ‘equity’ or ‘intersectionality’ rather than improving public services. If being a ‘staff Champion’ for the [protected characteristic] Network gains one more brownie points for promotion than driving efficiencies from operations or procurement, what do you think the result will be?

But more significant, electorally, is that it provides a weekly source of stories that any ‘outsider’ politician - such as Nigel Farage - can use to argue that the governing parties are out of touch with what matters.4 Donald Trump demonstrated how potently this can be weaponised, with his now infamous advert, ‘Kamala is for they/them, Donald Trump is for you.’5

Maybe most members of the public don’t care that ‘Starmer can’t tell you what a woman is’. Some do, and some are angry about it - particularly, perhaps, amongst activists.6 And sometimes a particular issue, such as the recent racially discriminatory sentencing guidelines issued by the Sentencing Council, touches a nerve and provokes widespread outrage. These instances do matter: they lower people’s confidence that the state is on the side of ordinary men and women, rather than in hock to special interest groups.

But equally important is the drip, drip drip of wondering why public services seems to have the funding for this while other services are closing, why schools or universities seem more focused on ‘decolonising’ their courses than providing a high level of contact hours for the fees their son or daughter is paying, or why the police seem more interested in talking to ‘community leaders’ than fighting crime. As someone commented in reply to Part Two of this series:

Failing to resource the criminal justice system

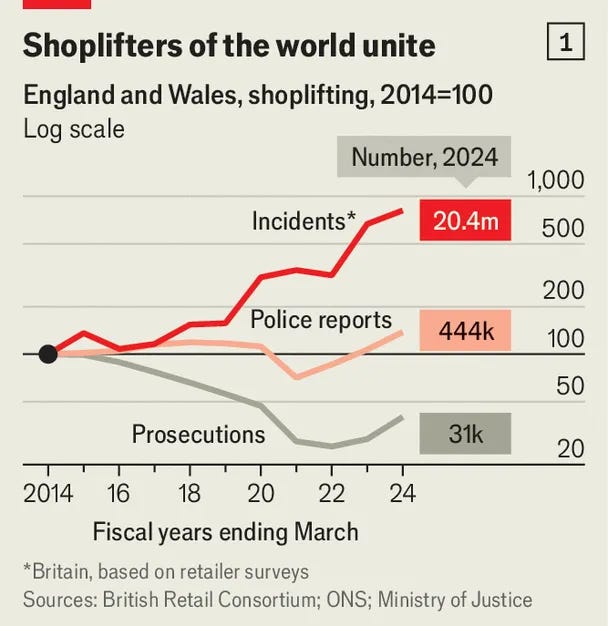

After decades of falling crime, the Crime Survey of England and Wales (CSEW) shows that crime is on the rise once more. In actual fact it’s worse than that, as the CSEW excludes various important types of crime, including crimes against business (such as shop-lifting), against the public sector (various forms) and others. Certain types of highly visible crime is in fact soaring:

Police recorded shoplifting is up 51% relative to 2015 and is at its highest level in 20 years.

Police recorded robberies are up 64% relative to 2015.

Police recorded knife crimes are up 89% relative to 2015.

Public order offences are up 192%.

As the graph below shows:7

But crime is still genuinely lower than 25 years ago - so why are so many people in despair about it?

There is a broader sense of permissiveness, that many types of crime, from phone-theft to shoplifting, have been in essence legalised. Even for more serious crimes such as burglary, the clearance rate is around 1 in 20 - and the police solved no burglaries at all in nearly half of all neighbourhoods in England and Wales. This forms a vicious cycle, in which people increasingly stop reporting certain forms of crime to the police, resigned to the fact that nothing will happen.

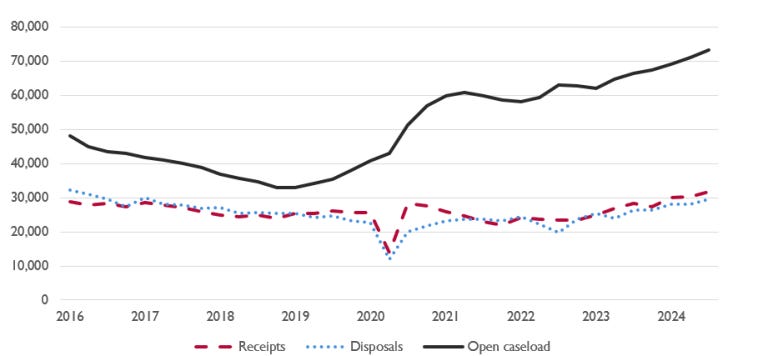

Even if the police do charge someone, the median time from an offence being committed to it being resolved in court is almost a year. Over 6,000 cases took more than two years to resolve! And the backlog is stubborn and growing.

Then, of course, if a criminal is convicted, they are not very likely to go to gaol. After rising in the ‘00s, between 2010 and 2024 the number of prison places per head of population fell slightly, from 152 to 141. In 2023, fewer than half of convicted ‘hyper-prolific criminals’ - those with 45(!!!) or more previous convictions - were sent to prison. And if you do go to prison, you may well be let out early: the scenes last summer, of convicted prisoners toasting the Prime Minister with champagne upon their early release, did little to inspire confidence in the system - and news this week says that it will soon be happening again.

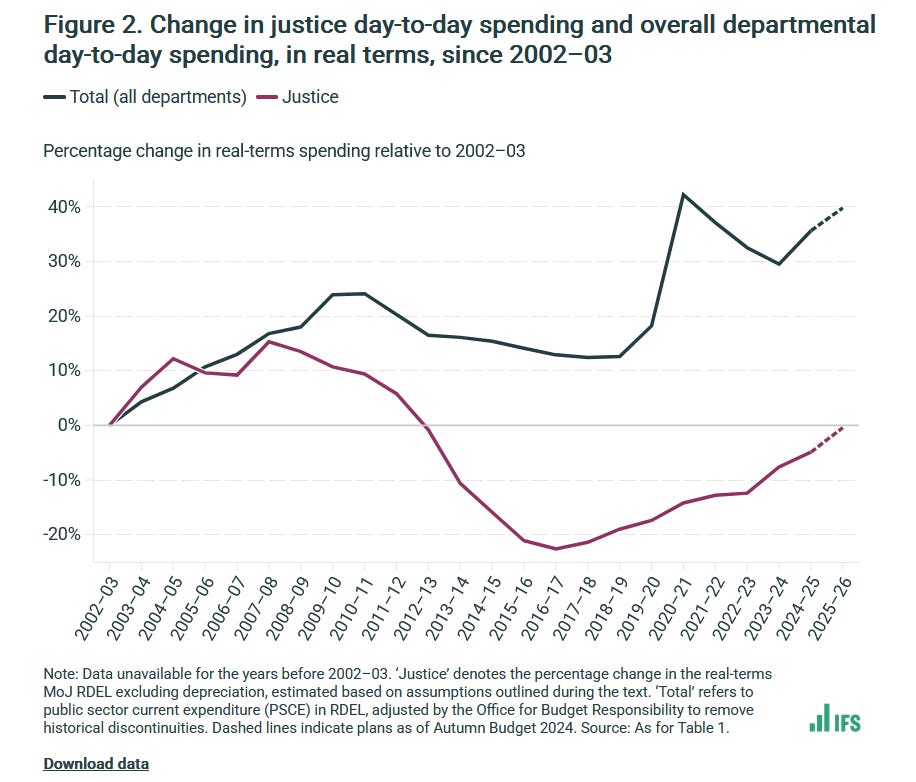

The truly astonishing thing is that this actually could be sorted out. Regular readers will know that I am not usually a big fan of just “spending more taxpayers’ money” - but the criminal justice system really was cut to the bone, and uplifts since 2020 have not fully reversed this

.

And the cost of sorting it would be peanuts.8 The entire cost - not the uplift required, but the entire cost - of the Courts and Tribunal Service is £2.3 billion. Legal Aid is another £2.2 billion. When the Criminal Bar Association went on strike, after years of real-terms pay cuts, let’s take a moment to reflect that there are only 2,400 of them - this is not a large number of people to buy off. Even prisons, the ‘big beast’ of the system, only cost £5.3 billion in running costs (though building more is expensive).9 These are genuinely small sums compared to the costs of pensions (c. £120 billion), Universal Credit (c. £80 billion), schools (c. £55 billion) and the NHS (nearly £200 billion).

One estimate is that sorting out the courts and the prisons would cost less than £3 billion extra per year. For comparison, the uplift in childcare announced by the Conservatives in spring 2023 was an additional £4 billion a year. That didn’t sort out childcare - but it could have fixed the justice system. On multiple occasions the Conservatives pulled ‘rabbits’ out their hat at fiscal events to announce additional sums of more than this for the NHS. And at the most recent Budget, Rachel Reeves increased spending by a whopping £70 billion a year - but Justice is still starved. A proper zero-based review would stop thinking about percentage uplifts or cuts and recognise that the justice system is both important enough - and, critically cheap enough - that it genuinely can just be funded well enough to just fix it.

No fan of public largesse, Margaret Thatcher was shrewd enough to realise that some areas of spending were non-optional - and before taking on the miners, gave the police a 45% pay uplift. Particularly for a government of the right, public order and criminal justice are not optional extras, but fundamental. And, indeed, for any government, failing to maintain law and order is likely to cost them dearly, for it is at the very heart of what people expect from the state.

A maximalist commitment to human rights law

This is fundamentally linked to immigration, discussed in Part One, but also to crime, public order and even foreign policy. In addition to throwing up individual cases with egregious results, it is leading to politicians making commitments that they are unable to follow through on under the current legal framework - notably the Rwanda plan, but more broadly almost any pledge concerning the Channel crossings or foreign criminals - which further drives discontentment and lack of trust in the political mainstream.

The European Convention on Human Rights was developed in the aftermath of the Second World War as a safeguard against a return to totalitarianism and tyranny. Since then it has developed into an instrument which provides courts increasing influence into the domestic operations of states - many of them far more liberal than the founding members of the Convention were at the time. The Living Instrument doctrine adopted in the 1970s dramatically expanded the Strasbourg Court’s willingness to create new rights or dramatically expand those that already existed, and the Human Rights Act 1998 then turbo-charged the influence of the Convention upon domestic law. We have moved from a system that guarded against fascism, to a situation where a court has ruled that a sex offender could not be deported to Afghanistan because he might be persecuted there for being a sex offender.

Even in recent years, decisions by the UK’s Supreme Court have had significant implications. In AM (Zimbabwe) (2020), the Supreme Court blocked the deportation of an HIV-positive foreign criminal because of the inadequate health service in Zimbabwe. Outside of immigration law, the Ziegler case in 2021 significantly reinterpreted the law regarding obstruction of the public highway for public protest, reducing the ability of the police and courts to deal with such matters.

In practice, although some UK politicians have criticised Human Rights Law, the practice in Government of all three parties since at least 1997 has been to accept the framework it provides without challenge.10 Although the UK Parliament has the legal right to legislate to address any of the matters above, it has chosen not to. This throws up challenges for the mainstream parties and an opportunity for outsiders, such as Reform: who are you on the side of, decent hardworking folk, or rapists and paedophiles? Do you stand for justice - or injustice?11

The situation has, however, gone beyond the impact of individual cases. It has become increasingly clear that under the current expansive interpretation of human rights law in the UK, it is effectively not possible for politicians to fulfil the pledges that both mainstream parties have made with regards to stopping the Channel crossings, or in terms of deporting failed asylum seekers, including those convicted of crimes. By cleaving to a maximalist interpretation of human rights law, the mainstream parties have hitherto decided - implicitly or explicitly - that this is more important to them than keeping their promises, or delivering on these policy commitments.

What is particularly damaging electorally is that this is, very clearly, a political choice. Most people understand that when it comes to complex systems, a politician cannot just wave a wand and improve NHS efficiency, create economic growth or attract business investment. These are genuinely difficult problems. But politicians could choose to override our current human rights law - they just have chosen not to.

I should emphasise that this does not necessarily mean leaving the ECHR or abolishing the Human Rights Act. Some people do think that, but others think things could be fixed by new guidance, or by clarifying laws. Others advocate derogations or carve-outs in certain areas. Some, such as Jack Straw, have said that the UK should leave the ECHR and rely on the Human Rights Act; others argue for reform of the Convention, and still others do indeed think leaving the Convention is the answer. It would be well beyond the scope of this piece to discuss the various merits of these - but suffice it to say this is not a binary issue.

Beyond immigration, legal maximalism has other consequences. We see it in the criminal justice system, we see it in payments to Gerry Adams, we see it in foreign policy. It lends itself to the question, who do you stand for: them, or us? The bizarre determination of the Government to cede a vital military base on the grounds of an advisory opinion by a foreign court - concerning a situation which the treaty explicitly says the court does not have jurisdiction over - creates a political gift. Most of the public may not be able to point to the Chagos Islands on the map - but they can understand that the Government was able to find £9 billion for Mauritius, but not for Winter Fuel Allowance.12

Not everyone believes that foreign criminals should be deported, that protesters who repeatedly vandalise property should be imprisoned or that there is a problem with economic migrants making unauthorised entry across the Channel. But the many that do expect their government to take effective action. By acknowledging the fundamental legitimacy of these concerns, mainstream politicians are in a cleft-stick of their own making. They have willed the ends, but not the means. And if they are not willing to take the actions needed, who will? Until the UK reaches a new accommodation with human rights law, the electoral potency of that question will not diminish.

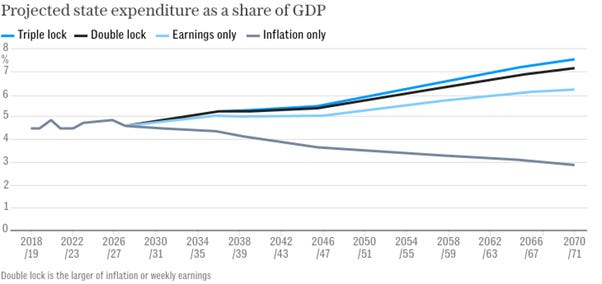

Maintaining the state pension triple-lock

There’s a web-game called Cookie Clicker where you click a big cookie to make cookies. After a little while, because it’s That Sort of Game, you’re mining the Earth’s core for cookies, converting distant galaxies into cookies and warping cookies in from parallel universes.

The state pension triple-lock is like this, except you don’t get to eat the cookies.13

In the early 2010s I can remember arguing it was fine to have a mechanism that gave bad results if extended to infinity, because it was helpful in the short-term and we could stop it when it was no longer useful. Turns out I was wrong about that, because I underestimated the electoral death-grip that the triple lock would exert over our political parties.14

The Triple Lock was introduced in 2010, in the context of a thirty year decline in the value of the basic state pension as a proportion of average earnings – from 26% in 1979 to 16%. It was also introduced at a time when increases to the state pension age were being accelerated under the Pensions Act 2011, and ensured that – although people would have to work longer – the value of the pension they received would be not only preserved, but increased.

The Triple Lock is expensive. It cost £124 billion in 2023-24 - around 10% of all public sector spending. During the period between 2010 and 2024, prices (as measured by CPI) increased by 49.7%, average weekly earnings increased by 55.6% - and the basic state pension increased by 73.6%, from £97.65 a week to £169.50 a week. In April 2025, the Government announced that, in line with the Triple Lock, the state pension would increase by £470 that year, and £1,900 more over the course of the Parliament.

Overall, it is costing £11 billion a year more than if pensions had ‘only’ risen by inflation and, if continued, we can see that it takes up an ever-increasing share of GDP.15

There were good reasons to introduce the triple-lock. But the state pension has now risen considerably in real terms. Pensioners are the least likely age-group to be in poverty: only 16% of pensioners are in relative poverty, compared to 21% of the population as a whole. Pensioners who have contributed all of their lives deserve a decent pension, but why is continuing to increase it even further a priority at the current time?

Of course, unlike some of the other policies we’ve discussed, the triple lock is not unpopular - quite the opposite. But the money spent as a result of the triple lock is one of the largest single contributors to why other areas of public services, from libraries to prisons, have faced real-term cuts. And this general deterioration of public services and the public realm, as we saw in Part One, very much is part of why the public are angry and seeking alternatives.

As a reader of this blog wrote recently elsewhere, the biggest problem in our politics is that the electorate have crushingly unrealistic expectations. They believe that we can keep spending more without having to raise taxes on ordinary people, that we can consistently increase major budget lines such as welfare, pensions and the NHS by above inflation every year without consequence - and they become very angry when the government lets them down.

It’s not unreasonable that they think this. From 1945 to 2008, this was basically the state of affairs - punctuated by the odd recession, but not for long. It wasn’t so long ago that David Cameron talked of ‘sharing the proceeds of growth between public services and tax cuts.’16 For that matter, Labour came to power last summer campaigning against ‘Tory tax rises’ as well as promising better public service. No political party has levelled with the British public.

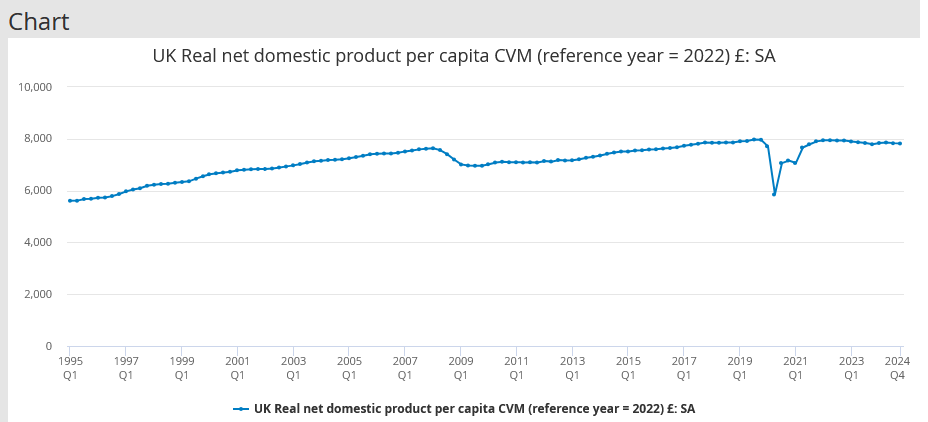

The truth is that Britain is not as rich as we think we are. Our economy is slugging, growth slow and GDP per capita has been falling since 2021.17 For decades, we have failed to invest at the levels of comparator nations. Tax is at its highest level since the war and borrowing costs at the edge of what the bond markets will tolerate.18 Increasing either will almost certainly hit our lacklustre growth still further.

The public are feeling it, at every level: and yet there is almost certainly a sharp readjustment coming in the next decade, if not voluntary, then forced. We can no longer afford to continue increasing pensions or benefits by above inflation each year, to spend more on the NHS while productivity declines, to send ever-increasing numbers of people to university without economic benefit, to over-regulate our economy, or to preside over a mass immigration system which is so unselective that many of those admitted are a fiscal drain. Perhaps we could afford to do some of these things - but not all of them.

So how to get out of it? This series is not a political manifesto: going into the next election pledging to abolish the triple lock, slash welfare and social care and take on the mental health lobby would only be a good idea for a leader looking to challenge Michael Foot for the record of the longest suicide note in history.

And yet, the country does need political leadership willing to level with the nation, to explain that we have been living beyond our means - and to connect the hard sacrifices necessary with the longer-term improvements in living standards that would result. This is hard, but not impossible: both Attlee and Thatcher managed it, as did Cameron to an extent. And doing so is what will ultimately deliver the economic growth needed to improve living standards, bring down taxes and invest in public services.

Other changes require fewer sacrifices and are even easier to deliver - if our leaders are willing to abandon some sacred cows. It is eminently possible to control our border, restrict immigration and deport violent criminals - if we legislate explicitly to do so. Controls on university numbers existed until 2014: they could reimposed. And an abundance agenda in energy, encouraging investment simultaneously in renewables, oil and gas and nuclear, is likewise blocked by nothing other than ideology. These sort of changes would have direct benefits - but also reassure the public that the Government was tackling the issues they cared about.

Of course, all of this needs to actually be done. Not just talking about building new homes - but building them. Not talking about scrapping red tape - but doing it. And there is no point in half-measures, either. As the Conservatives found out, and Labour are rapidly discovering, when times are tough, triangulating so that everything gets a little bit worse wins you no friends at all. Just as in 1945 or 1979, incremental tweaks to the status quo won’t cut it. We need significant changes - at least in some areas.

None of this will be easy. And yet, if the country is not put back on the right track, the public will keep voting for change, until they find someone who will. Maybe that will be Reform - although it is far from guaranteed that they will actually make things better. Maybe the country will keep stumbling along, under one form of minority government or another, until the IMF gets called in and bails us out. Or maybe, just maybe, one of the larger parties will step up and deliver.

There is no guarantee. Britain has no God-given right to be a wealthy nation. Other nations before us have dwindled and declined - and we have been on this path for many years now.

But while there is no guarantee, there is hope. In recent history, Greece, Spain and Portugal have all faced worse challenges and overcame them - as did Poland, South Korea and Ireland. All that stands between us and a return to growth, prosperity and optimism is the right policy choices. We just have to have the courage to make them.

This is the second of three posts on understanding Reform’s success in last week’s Local Elections, why Britain Isn’t Working - and why this is driving people’s search for an alternative, any alternative. If you’ve not already, you can read Part One here and Part Two here.

Albeit one that builds on what has come before.

Including the current Leader of the Opposition.

No, refuse collection and administrative jobs are not the same. Nor are warehouse and shop front

Note that this can be a double-edged sword: a politician who focuses too much on being ‘anti-woke’ can also be seen as focusing on what doesn’t matter.

As an added bonus, this advert, featuring sex changes for prisoners, also managed to imply that Harris was soft on crime - another traditional Democrat weakspot.

This element of it probably hurts the Conservatives more than Labour.

At this point I’ve included a chart from Archie Hall in all three posts of this series, so I should probably say that, as well as writing for the Economist, he has a great substack - go check it out!

Compared to overall public expenditure.

The one significant exception to this was Cameron’s decision to defy the European Court of Human Rights on granting the vote to prisoners.

For most people, if a person is seeking asylum in the UK, but is then convicted of a serious crime such as the rape of a child, justice would demand that their asylum claim is voided and that they are deported - even if they have come from a dangerous country such as Afghanistan. But under our current legal framework of human rights law and other international treaties, this would be unlikely to happen: one would need to consider their right to family life (do they have a partner here, etc?), issues around refoulement and so forth. Defenders of the ECHR might argue that this is indeed justice - but to many others, this is actively unjust.

I’m aware the sums don’t match, and the dangers of comparing annual and total amounts. This does not diminish the electoral potency.

Technically speaking, you don’t get to eat the cookies in the game, either.

There’s a (fairly good) science-fiction book, The Uploaded, in which dead people can be digitally uploaded and live in cyberspace. The only snag is that the (US) Supreme Court rules that uploaded people can still vote - and soon the living are reduced to lives of servitude and penury to maintain the ever-growing server farms of the dead. I like to think the author was inspired by the triple lock.

As, indeed, it is inevitably designed to do.

Though this was before 2008.

Higher than after the Liz Truss Minibudget.

A good first step would be abolition of “National Insurance” which is not “national” and has only a vague residual connection to pre WWII systems of social insurance. It remains now as an additional tax on employment and causes significant confusion with ordinary commercial insurance/assurance where someone’s contributions are directly linked to what they will eventually get. There would be ways of reforming this. In Germany, for example, the Rentenkasse is a separate fund itemised on salary slips, and it is clearly visible how the contributions being paid in are distributed at the same time to those being paid out (and the share of payment out is linked to what you previously paid in). The alternative could be abolishing NI and creating a “state old age benefit” paid out of general taxation (taxable if not means tested) designed to provide a minimum safety net and making it clearer that anyone wanting more than this in retirement should save privately

> They believe that we can keep spending more without having to raise taxes on ordinary people, that we can consistently increase major budget lines such as welfare, pensions and the NHS by above inflation every year without consequence - and they become very angry when the government lets them down.

We *could* do this, but they probably wouldn't like the third set of tradeoffs -- having above-inflation productivity growth again would involve building homes, infrastructure, factories, and energy generation; letting companies go bust; and sunsetting cities.

We have a kind of trilemma -- low taxes, high spending, zero building: drop one. Personally, I think we should drop 'zero building', but that's just me.