Britain Isn't Working (Part 1 of 3)

Understanding the rise of Reform

The first of three pieces on understanding Reform’s success in last week’s Local Elections, why Britain Isn’t Working - and why this is driving people’s search for an alternative, any alternative. Part Two can be read here and Part Three here.

There’s a basic trade-off in politics. Want better public services? Then you’ll have to pay higher taxes.1 Or want lower taxes? Then your public services will probably get worse.2

Governments can be successful on either of these platforms. Blair and New Labour did well with the first; Thatcher with the second. As with so many things, there tends to be a pendulum on these matters, but the basic equation holds. Until now.

Since about 2015, in the UK, the tax burden has risen year-on-year as a share of GDP, but public services have got worse. Even in the Coalition years, where taxation fell slightly, this was nothing like the large falls we saw under previous governments. Now, that was probably sensible, as they were reducing the deficit, but it meant people saw nothing like the boost in disposable income to make up for the cuts to front-line services that would have been seen in other eras. And since then, taxes have steadily risen, with services (except the NHS and schools) facing the pinch.

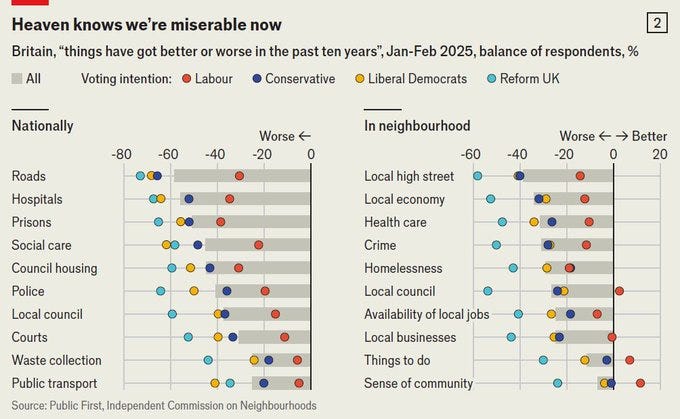

And across the board, people feel - in most places correctly - have got worse:

Alongside this, many people feel that in a whole range of ways the country has gotten worse. Bins are collected less often.3 Crime is on the rise again, with some particularly visible crimes such as shop-lifting soaring4 - and criminals are being let out of gaol because they’re too full. More people play music without headphones on public transport. And on a whole set of cultural issues, people feel ignored and let down by mainstream politics. The most important of this, electorally, is immigration, with both the surge in legal immigration and the failure to stop the boats crossing the Channel, but identity politics more broadly, including trans, ‘decolonisation’, two-tier justice and other such issues all contribute to the sense that the UK’s leaders5 are fundamentally out of touch with the nation.

In 2016, people looked to Brexit to solve their problems - but politicians spent three years arguing.

In 2019, they elected the Conservatives to Get Brexit Done - which they did, but didn’t do much else.6

In 2024, thinking a Labour government must be the solution, they kicked out the Tories - only for Labour to also increase taxes, cut (some) benefits and not, yet, improve public services7 - while immigration continues to surge.

So last week they turned to Reform - and, to a lesser extent the Liberal Democrats. Not because they have fallen in love with Reform’s policy platform - which is scanty. But because they are angry and upset, they are crying out for change - and having been repeatedly let down, they are willing to try one more thing.

So, why? Some would say it is all down to demography, to an ageing population or to Baumol’s cost disease. That, no doubt, plays a part. The COVID pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine certainly played a part. For many in this camp, the answer is just to tax more - but tax is already at a record high as a proportion of GDP, and doing its part to suppress growth. Others say we should borrow more, and rage at the Chancellor’s fiscal rules - but while these specific fiscal rules are poor8, it’s the bond markets that are the real limit on debt, with the price we have to pay to borrow higher than after Liz Truss’s minibudget.

The truth is that over the last 10-20 years, both parties have been committed to a set of policies that have immiserated Britain. Talk of a ‘uniparty’ is overdone - Labour are doing things that the Tories would never do, such as taxing private schools, and similarly the Conservatives did things that Labour would never do. But on a core set of important policies, from mass immigration to university expansion to not building enough homes, there has been a remarkable consensus in practice.9 These policies have primarily been of two types:

Pro-Boomer policies: policies that favour the protection of accumulated wealth by the older generation over the ability of the entrepreneurial and hard-working young to realise the fruits of their labours.10

Pro-Anywhere policies: policies that prioritise the interests of, in David Goodhart’s terms, the ‘Anywheres’ over the Somewheres - though it should be noted that such is the combined impact of these, they are now starting to harm (most) Anywheres as well:

This piece, in three parts, will look at twelve of the most significant of these and why, collectively, they mean Britain Isn’t Working:

Not building enough homes

Addiction to mass immigration - and failing to control the border

Permitting the numbers on out-of-work benefits to soar

Tolerating and exacerbating high energy costs

Uncontrolled university expansion

The spiralling cost of regulation

Not facing up to the rise in mental health and special educational needs.

Hollowing out Local Authority budgets

Encouraging the growth of radical identity politics

Failing to resource the criminal justice system

A maximalist commitment to human rights law

Maintaining the state pension triple-lock.

All of the above are policy choices. Some are more explicit than others - people have championed university expansion far more than not building enough homes - but all are policy choices, and all are in the ability of a government to change - if they wish to.

And whether you are on the left, and would like more money for the public services or redistribution, or are on the right, and would like a smaller state and tax cuts, the cumulative impact of the policies above are now directly impeding your goals - and contributing to the general immiseration of the country that was expressed so loudly by people’s voting decisions last week.

Preamble: When is a cut not a cut?

As the election results were unfolding, centre-left commentator Sam Freedman posted a thread on BlueSky arguing that the primary reason for Labour’s unpopularity was the cuts:

He has a point here: every focus groups shows that the cuts to winter fuel allowance and to disability have been deeply unpopular. But there is something more complex here: how can people be angry about cuts when tax and spending are at record levels?

There are two reasons:

Successive governments have significantly increased government spending in areas only some people benefit from, leaving much less available for broad-based public services. The biggest example is the triple lock, which has meant the state pension (at £130 billion a year, a very significant part of public spending) has increased by above inflation most years; another example is social care, and we’ll see in Part Two how social care spending has swelled, leading to major cuts in almost all other areas of local authority services (manifested in reduced bin collections, more pot holes and closed libraries).

In numerous areas, successive governments have abrogated their responsibility to control the number of people accessing or eligible for a service, seeing this as too politically difficult. As a result, the butter is spread too thin, with those formerly eligibile seeing a cut, or worse service. The obvious example is welfare, where claimant numbers have soared - and we’ll show below how the current Government’s ‘cuts’, while very real for many recipients, still leave the budget rising in real terms. But we see this phenomenon again and again, including in higher education and in special educational needs.

Now, on to the main section and the first four policies:

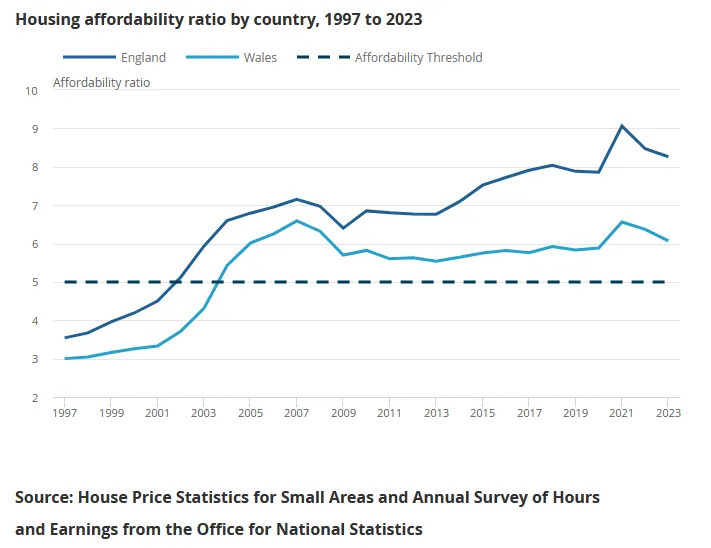

Not building enough homes

For at least three decades we’ve failed to built sufficient homes to keep pace with population growth. The result has been house prices soaring as a proportion of income - as well as rent rising, and the outlay on housing benefit soaring, as we’ve failed to build enough social housing.

The result is an increasing proportion of personal incomes going into housing costs and an increasing amount of capital diverted to a less productive use.11 It exacerbates inequality, as whether or not you can get on the housing ladder depends increasingly on whether your parents can help you out (or if you inherit wealth); it delays family formation; and it undermines the basic social contract that if you work hard and do the right thing you can own your own home.

Our bad planning system has negative effects in many other areas - making it harder to build energy infrastructure, rail lines, reservoirs and laboratories. All of this depresses the economy and makes us poorer. But it is in housing that people can see the impact most directly on their lives.

To date, Governments have mainly responded to this by stoking demand.12 To solve it there really is no alternative but to build more homes - including where people don’t want them - something which successive Governments have talked about but not been willing to do at anywhere near the scale needed.13

This will be unpopular in the short term, but people adjust rapidly to living in a larger town, or a new town - and is the only way to seriously alleviate the current situation.

This issue links strongly to the next one - for, as I wrote earlier this year, mass immigration takes the already difficult problem of building enough homes and transforms it into one that is nigh on impossible.

Addiction to mass immigration - and failing to control the border

Sustained mass immigration puts pressure on the housing supply, driving up house prices and rents and displacing long-term residents in the queue for the limited supply of council houses.14 It increases pressure on public services, both in relatively benign ways (more school places needed, more NHS appointments), and in less benign ones (additional demand for translation, cash-strapped councils paying millions for taxis to takes asylum seeker children to schools).

Mass immigration also depresses wages15 - which we saw clearly in the early ‘20s, when HGV driver wages increased due to a shortage. There is also a more insiduous effect whereby an addiction to immigration reduces the incentive of businesses to invest in and train up the domestic work force, because it is easier and cheaper to just import someone. And, indeed, the Institute for Fiscal Studies finds that the average employer spending on training has decreased by 27% per trainee since 2011.

There are also non-economic reasons why some people are opposed to immigration. Integration takes time; building a cohesive society amongst people of different cultures, languages, faiths and values takes time. And as Ed West has eloquently set out, rapidly bringing in large numbers of people from different cultures, particularly from low-trust societies, is not compatible with maintaining a high-trust society - with all the benefits this brings.

Fairly obviously, scale matters. As I’ve said before, my Dad was an immigrant - but when he arrived in 1983, net migration was 17,000 a year. Last year it was over 900,000 - or over 50 times as great. The challenges involved in managing the latter are incomparably greater than the former. And even after the restrictions brought in at the end of the Conservative Government, and maintained by Labour, kick in, the OBR is still forecasting net migration to remain at around 300,000 a year, well above the level during the New Labour years.16

But on the economics, the received wisdom has been that mass immigration is necessary to sustain the economy - and that this outweighed the challenges set out above, whether on public services or on integration. Well, it turns out it does increase GDP - but it doesn’t increase GDP per capita, which is what really matters. If most immigrants receive more in public services and benefits than they contribute, this doesn’t mean they are bad people - but it does mean they are making the country poorer.

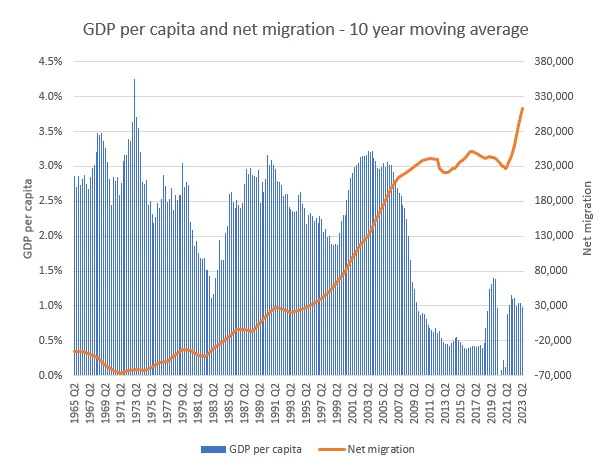

One reason to be dubious that immigration is making us richer is to look at the history: increasing immigration has coincided with a collapse in growth in GPD per capita.

But correlation is not causation17 - perhaps both trends could be caused by some underlying factor. So let’s see what the OBR says about the contribution of migrants

We can see here that low-wage migrants - this would include many of those coming in to do jobs in low paid roles such as social care or fast food18 - have a net negative fiscal impact throughout their whole lives. In many ways this shouldn’t be surprising: more than half of UK citizens will receive more from the system than they pay in - that’s the entire point of a progressive tax system.19 But it means it’s quite hard to make the country richer by importing people unless they are genuinely high paid (e.g. doctors) or filling a skills gap which is holding back an important industry (e.g. certain types of engineering).

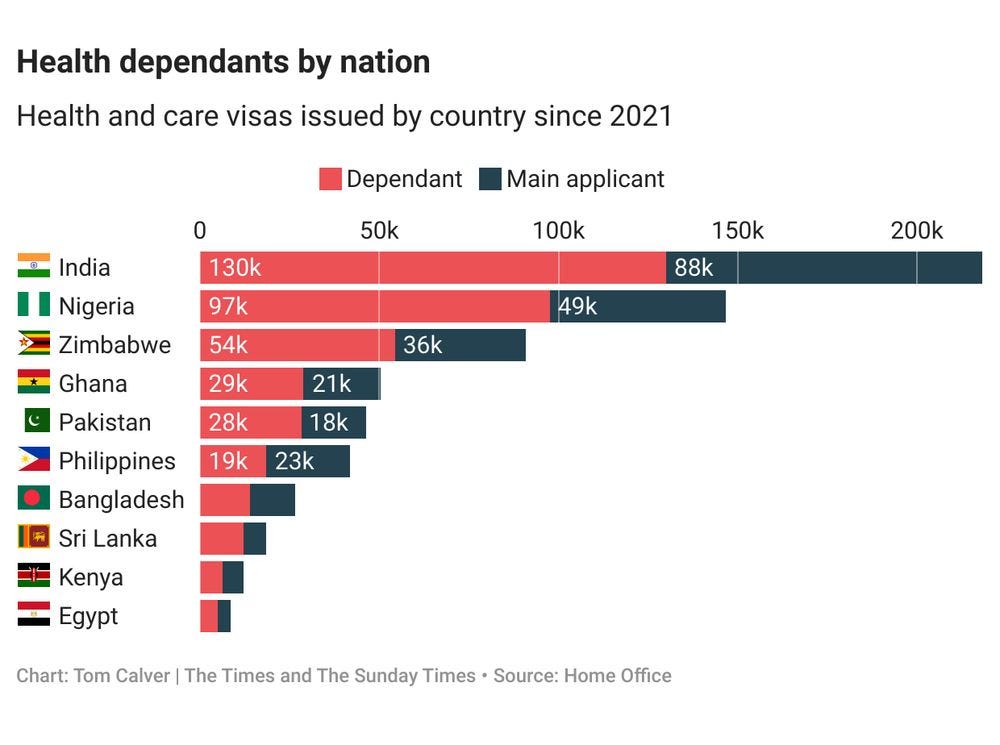

But in fact, the actual picture is much worse than the OBR chart makes out - because many of these immigrants bring in dependents. Of over a million non-tourist visas granted last year, only 210,000 were granted to main applicants in all work categories. Some nationalities - and some work visa routes, such as the health and social care visa - seem to bring in far more dependents than others, with Indian, Nigerian and Zimbabwean health and care work visa entries bringing in more than 1 dependent each. Given that many jobs in social care pay little more than minimum wage, this is clearly not making us richer.20

And what about students? On the surface, students who come here, pay high international student fees to support our universities, and then leave, seem like a good thing. And they are!21 But that isn’t actually what - in most cases - is happening.

It certainly used to be the case that that was what happened. But things have changed. The ONS has said, “More non-EU+ students and their dependants have been staying longer, and nearly 1 in 2 transitioned to a different visa type after three years from YE June 2021; an increase from 1 in 10 after three years from YE June 2019.” And this seems to be increasing: if we look at the year ending 2023, a stunning 46% of those who arrived on a study visa had moved on to a family, humanitarian or other work visa within a year.

And they are disproportionate arriving to do Masters, and to lower ranked universities:

So rather than the image of high ability young people coming to study which we think of when we think of student visas, what we actually see, overwhelmingly, is people paying for a one-year Masters, at low-ranked universities - and with a high proportion transitioning of a student visa on to a non-working visa within three years. Universities are selling immigration, not education.22

Of course, not all immigration is economically negative. The c. 30,000 doctors who came to work in the NHS are almost certainly a Good Thing. And none of this is to criticise individualscoming here to seek a better life - who can blame them for using the lax rules our governments have put in place? But if we want immigration to contribute positively, not negatively, to our economy, we need to be much more selective over who, and how many people we admit - something which Neil O'Brien has written about here.

Small Boats

And then, of course, we have the small boats. The numbers involved are relatively small as a proportion of overall migration23 - though the absolute costs to the taxpayer, at over £5 billion a year, are non-trivial, as is the impact on some communities and councils.

But the greater damage is in the very clear demonstration it provides of successive governments being unwilling to enforce the borders. To cut through electorally, an issue typically needs to both be genuinely serious, and have an element that is visual and emotive. The small boats provide the second element, a visceral example of failure, that turbo-charges concerns over immigration - legal and illegal - and makes them electorally potent.24

Permitting the number of people on out-of-work benefits to soar

It is slightly unfair to say this is an area where there has been consensus amongst both parties for the last two decades. The Coalition Government made serious efforts to reduce the number of welfare claimants - and successfully got the number down. But from about 2018 the number began creeping up, it soared in the pandemic and then, after falling slightly afterwards, has begun rising sharply again. And it’s a major factor in why - literally! - Britain Isn’t Working.

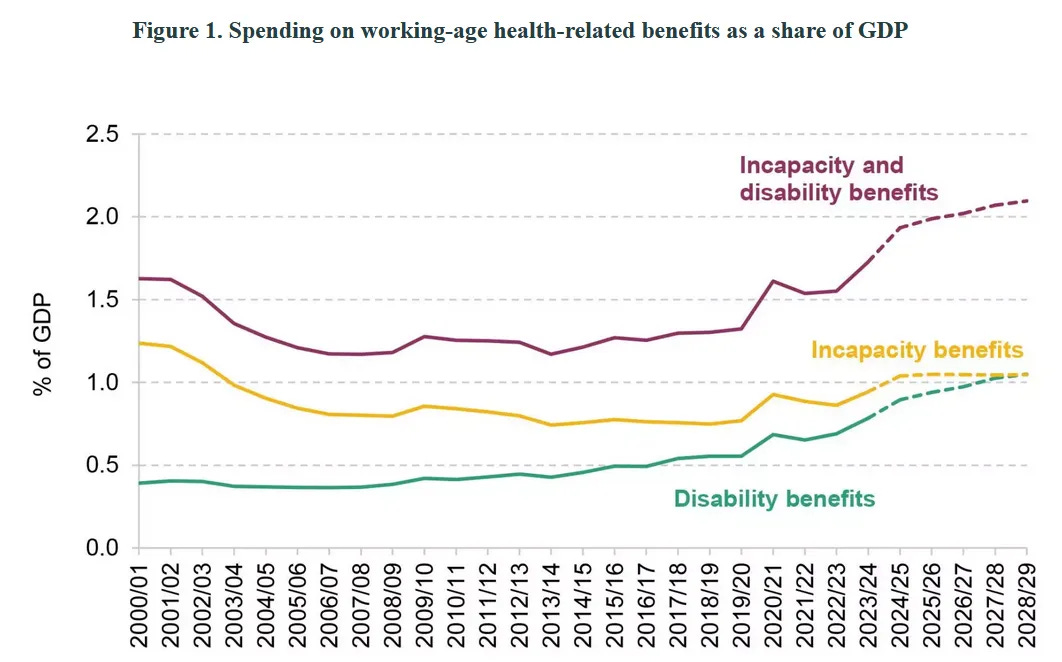

This is not ‘Long COVID’. More than half of the rise in 16-64 year-old claimants is due to mental health health or behavioural conditions. There has been a sharp increase in the number of young people going straight from education on to disability benefits - primarily for mental health reasons.25 And spending on working-age health related benefits is on track to double as a share of GDP.

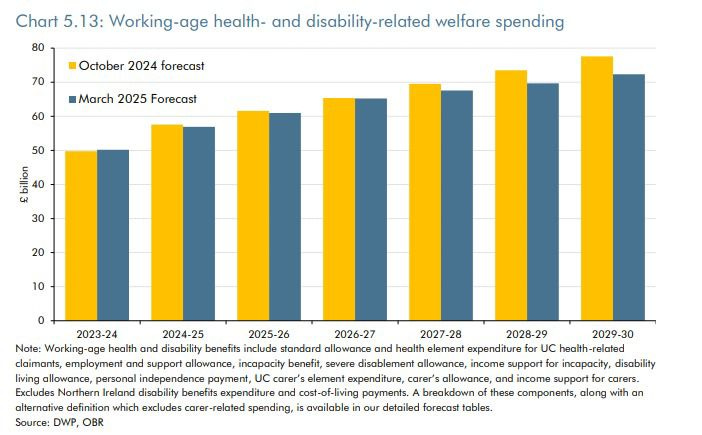

The current Government’s ‘benefit cut’ - though it will indeed be a cut for some people - will not actually reduce spending. Instead, the budget will be increasing by ‘only’ £15bn, instead of £20bn - still a good 15% or so above inflation.

And of course, every person claiming out-of-work benefits is not just a direct cost to the taxpayer, but represents an opportunity cost, as that person could instead be in work, supporting themselves - and paying tax to support others.

Tolerating and exacerbating high energy costs

The UK has some of the highest energy prices in the world. This impacts the entire economy:

It makes household energy bills more expensive, increasing the cost of living.

It means companies have to pay more to manufacture things, light their shops or heat their offices, making goods and services cost more.

It shapes decisions over whether companies - particularly in energy-intensive industries - invest in Britain or elsewhere in the world, reducing GDP growth and job creation.

There are a number of factors contributing to this, including the fact that we are an island and that solar power is less efficient here than it is in, e.g. Texas. But one major factor is the speed and level of subsidy we have been giving to build renewable energy while, crucially, also failing to invest in nuclear and/or domestic gas production.26

Although wind and solar can be cheaper than fossil fuels, they are intermittent, so one needs a lot more of them27 to provide demand at all times, as well a more robust electricity grid. Also, most of the cost of renewables is up front, building the infrastructure. The Government smoothes this out by means of various mechanisms, including the ‘Contract for Difference’ policy, where they guarantee producers a certain price for the electricity they produce for a number of years. This leads to the subsidy for renewables and grid upgrades on our energy bills being about 30-40% of the total cost.

Now, there are very good climate change reasons to invest in renewables. Many people will rightly tell you that people are worried about climate change and that Net Zero is popular:

Added to that the price of renewables has been coming down a lot in the last two decades, meaning that there’s good reason to think that transitioning into a mainly renewable grid is a smart thing to do.28 But while people aren’t directly turning against the mainstream parties - or to Reform - explicitly because of Net Zero policies, we should recognise the ongoing cost of this does drive other unpopular choices - whether that is benefit cuts or tax rises. The issue is less investing in renewables, but more the premature shuttering of oil and gas resources (and nuclear).

The solution to this, for political parties, should not be to start wanging on about how Net Zero is ‘woke’, but rather to judiciously moderate our activities, so that we continue to reduce our carbon output at a proportionate rate, whilst keeping other sources available while we need them - while continuing to talk about the importance of tackling climate change. An energy abundance strategy, such as the one successfully implemented by Joe Biden as President - which saw record investment and increase in renewables but also record oil and gas production - would deliver better outcomes for the country than our current approach.

Though you can hope it won’t be the ones you use!

Yes, people really do care a lot about bins. Ask any local councillor.

Interpreted broadly - including those who have authority in major public sector bodies, corporations, universities and so forth.

Admittedly, a global pandemic didn’t help.

Some are trying. But reforming the NHS takes time.

Setting a limit based on a highly uncertain forecast five years away, and then treating that as a target to get as close to as possible, really is not a sensible way to plan.

This is the time for your regular reminder that while the Conservatives talked a lot about sending people to Rwanda, cracking down on low quality university degrees and stamping out ‘wokeness’, they did not in fact do any of these things.

As someone on the right, I am obviously all for property rights. But right-wing parties only function well when they also allow people to get ahead by working hard, starting businesses, being entrepreneurial, not purely those who have already accumulated property and wealth.

Buying property so that it will increase in value - or to extract higher rents - is less productive for the economy than investing in factories, construction, R&D or business.

For example through Help to Buy.

Though Cameron and May, and now Labour, are trying more than some.

Another policy choice.

Despite the protestations of some Anywheres, the laws of supply and demand do apply to labour economics.

And net migration estimates have historically been underestimates, so there is a good chance it will be higher.

‘Chef’ being classed as a skilled occupation, this has allowed kebab shops and fast-food restaurants to sponsor migrants under the Tier 2 route.

The top 1% pay 29% of all income tax; the top 10% pay more than half of it.

And yes, if we didn’t have this migration, we would have to pay British people more to do these jobs. I don’t really understand how anyone who considers themselves ‘progressive’ wouldn’t see that as a positive!

I have many friends who did this.

#NotAllUniversities, etc.

Though would have been large by pre-1997 standards.

There are obvious links here with human rights, which we will look at in Part 3.

Some of which will be discussed in Part 2, in Failure to Confront Mental Health and Special Educational Needs

The wholesale price is typically set by the gas price, so this really matters, as we saw when Russia invaded Ukraine.

Or, alternatively, a lot of storage which also costs money.

Though again, there is little environmental gain to being a ‘world leader’ in this when we make up only 1% of the world’s carbon output - or if we only do so by offshoring our steel and manufacturing industries to countries where they use coal.

Definitely prefer several shorter posts over single longer one 🙂

Hope you can edit and then delete this comment, but just before Footnote 12 you say 'stoking supply' when you mean 'stoking demand'.