We need a NICE for education

In healthcare, the organisation NICE - the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence provides a vital function. Despite literary foreshadowing, it is not a sinister organisation under the control of a demonically possessed severed head plotting global domination1, but is rather a bunch of health economists, statisticians and similar who carefully work out how which medicines and procedures can be afforded on the NHS.

NICE currently considers that if an intervention costs up to £20,000 - £30,000 to provide one ‘Quality Adjusted Life-Year’2 then it will generally consider it good value for money - and allow it to be funded. In other words, if a new cancer drug is discovered that could save lives, but only at the cost of £100,000 a year, then it won’t be funded.

In fact, this sort of thing happens all the time. It can undoubtedly lead, at times, to hard decisions. We have occasionally been on the end of these. As someone whose Youngest has had severe medical issues3, we’ve sometimes been told that there’s just no more they can do in a certain area, that more scans or more investigations wouldn’t be considered worth it, because it’d be so unlikely4 that they’d find anything else out. That’s never easy to hear. And this, of course, pales compared to someone who knows there is a drug out there that might - even at a 10% chance - stop them from dying, but they can’t have it.

However, it’s the only way to fairly allocate finite resources. And resources are always finite.5 The alternative, the ‘just one more scan in case’, the ‘try this drug, even though it’s unlikely to work’, we can see in the US, where the nation spends twice as much on healthcare as the UK, for no better health outcomes6. Desperate people and compassionate doctors, without guidance such as that which NICE provides, do not make good decisions.

What’s happening in education?

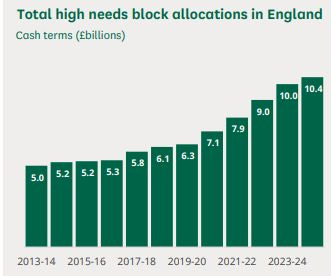

There is nothing remotely as robust in education7. And that matters, because the proportion of people

In fact, schools have roughly twice the funding per pupil that they did in the late 1990s, when I was at school. If it doesn’t feel like this sometimes - if schools are saying that they have to cut music, drama, specialised teachers - it is in large part because of the ballooning cost of the SEND Budget.8

The proportion of children with SEN has increased by 11.6% to 13.6% from 2015 to now. What's more, the proportion of children with an EHCP has almost doubled - to nearly 1 in 20 children. At the upper age of school this becomes even more extreme. 1/3 of children now get extra time in exams (42% in private school). And in Wales, nearly half of children who were born in 2002-3 were classed as SEND at some point in their childhood.

But even this, in itself, doesn’t account for all of the costs increases - which have increased at an even faster rate than the diagnoses, doubling in just 8 years. A system where LAs must meet identified 'needs' - regardless of affordability, or whether these needs could be met in other, more cost-effective, ways, is at fault. And private providers have spotted the opportunity provided by ill-thought-through statutory duties and have made a killing at the taxpayer's expense9.

One can question the extent to which the increase is real. Some might be - perhaps due to the influence of social media, or of lockdown. But to what extent are we medicalising normal human variation? Some of the new diagnoses and syndromes appear to have little contact with reality, my favourite being ‘Pathological Demand Avoidance’, used to describe a person who does not like to be told what to do. I know at least one two-year old who’s been diagnosed with it.10 Even for those labels where there may be a more legitimate basis, are we really doing children any favours by teaching them that personal challenges may be excused and allowed to persist, rather than worked on and overcome?

And yet, at the same time, there can be no doubt that there are many children with very serious needs, both physical and mental. This only increases when we also consider those children in care, many of whom have heart-breaking backgrounds and desperate needs.

But what are we getting for it?

Anyone who’s not been in a school - particularly a large state secondary school - for a couple of decades would be astonished at the number of children who now have full time one-to-one support from a teaching assistant. Many others have significant support, if not full time. And there will be still others - less visible to the casual visitor - who are ‘school refusers’, who do not come into school, but have tailored work sent home to them each day.11 The number of teaching assistants employed by state schools in England trebled between 2000 and 2020, to reach a quarter of the work force.

This is not cheap. To provide full-time one-to-one support costs from a TA costs around £25k - £35k12 That means that child is getting 3-4 times the c. £8,000 average funding per child spent on their education. To what extent are they benefitting from this? Is it improving their GCSE outcomes, their life outcomes, their personal outcomes? Does it vary based on why the child is getting that support?13 How would the 30 other children in the class benefit, if that money - or some of that money - instead was spread more evenly? At a time when schools are cutting back on general facilities, specialist teaching and elsewhere, these are questions that should be asked.

These costs, of course, pale compared to those with SEND who are sent to special schools, where the typical cost (borne by the taxpayer) of sending a child to an independent special school is £61,000, and can be considerably higher. And these in turn are dwarfed by what is spent on children in care, where in over 1,500 cases we are spending more than £10,000 per week - or over 50 times what we are spending on the typical child for their education. Alarmingly, that figure has increased more than 10-fold since 2018-19, when only 120 children were receiving that level of spend.14

There can be no doubt there is much real need in these situations. Nor can we doubt that some interventions are highly effective. Providing a partially sighted child with a screen reader can enable them to access learning as effectively as a child without a disability. Intensive early support for a child with dyslexia in reading can see dividends across all of their subjects, throughout their time at school. Undoubtedly, some of those at special schools or in care have very great levels of need.

But at the same time, the outcomes of children with SEND, or with EHCPs, or in care, are not showing significant improvements. In many of these cases they continue to lag across almost all metrics, whether academic, social, professional or others. Of course, we do not know the counterfactual. But nor are we even trying to establish it.

Given the amount being spent, there are minimal efforts to match costs to efficacy - or even to measure efficacy at all. ‘Need’ is identified, and statutory requirements then require schools, or local authorities, to provide certain provision with minimal abilities to control costs, but whether what is provided is efficaceous, or cost-effective, or could be provided more efficiently in another way, is hardly looked at - and certainly does not feed back, in any systematic way, into how other schools or local authorities are providing, or required to provide, support.

We Need a Nice for Education

No-one would doubt that many of these children require more support - and very few would argue that we should not provide it, even if that means some children have more spent on their education than others.15 But we need a much better understanding of what works, what is effective, and what is of value.

We should be assessing, for children with a certain type of need, how much difference do certain interventions - whether that is a screen-reader, one-to-one TA support, a special school, or different types of care provision - make, on average? This would include very basic academic metrics, such as increases in average GCSE score, or SAT performance, which we already measure. It should also assess other life outcomes. Without being prescriptive, this could include matters such as the likelihood of being employed, or of staying out of prison, or in avoiding homelessness. For the most severe forms of need, it could consider whether it enables independent - or partially independent - living: the ability to cook, dress and otherwise take care of oneself. And it should then compare the improvement in outcomes to the cost being spent - and draw a line across, above which cerrtain interventions were not considered value for money, and would not be funded.16

This would not be straightforward and it would need to be done carefully, objectively and sensitively, immune, as far as is possible, from both political interference and the demands of single-issue lobby groups. In other words, it should be done in the way NICE assesses the impact of healthcare interventions. And while the above is complex - particularly in weighing up the impact across different types of outcomes - it is no more difficult, and no more sensitive, than the work that NICE does in assessing how conditions such as pain, mobility, use of bodily functions and so on combine to constitute a ‘Quality Adjusted Life Year’.

Despite the title, I am unsure whether this requires a fully independent body, such as NICE, or whether it could be carried out by an independent committee and experts sitting within an existing body (or even by a new division within NICE itself). The quantum of funding involved - over £10 billion a year - makes a dedicated body appear justifiable, but an existing body could be more efficient, provided it was given the independence and objectivity to work. Where it sits, or how it is constituted, is less important though than that the work is done.

A NICE for education would allow hard, but necessary, decisions to be made fairly - and for the money we are spending to be used in the way that benefits all children the most. Given the scale of the cost, and the impact on the system as a whole, it is not just necessary - but long overdue.

See That Hideous Strength

This means that an additional year lived in good health is considered to be worth more than a year lived in severe pain or other debilitating condition.

Without wanting to go into detail on a public forum, we’re talking of a scale of seeing multiple specialists at Great Ormond Street, many hospital overnight stays - some planned, some not - and multiple operations.

But of course not impossible

It is also clearly better, in circumstances like this, to have a more distant, objective, organisation make the decisions than forcing this on to doctors with patients right in front of them.

US life expectance is actually considerably worse than in the UK, but this is mainly due to a lot more people dying before 45 - primarily from drug overdoses, homicide (via guns) and car accidents. Life expectancy from 75 is extremely similar.

By which I’m basically meaning schools, in this piece.

There are some other reasons, including a growth in pointless paperwork and bureaucracy - my old school now has an ‘admin block’ where once it just had a school secretary! - but this is, relatively, minor (though still something we should try to reverse).

Private provision is not wrong per se - but the combination of profit-incentives and inflexible statutory duties has proven a toxic mix.

So, completely unlike every other two-year old ever, then.

Is it really helpful to these children to teach them they don’t have to come into school? Maybe for a very short time - perhaps after a traumatic incident - but long term? Or could this be connected with the fact that the proportion of young people moving straight from full time education to disability benefit has doubled, with over 60,000 doing so each year?

Based on the costs of a TA salary (which can vary considerably) + NI + pension contributions.

Almost certainly.

There is an excellent discussion of how costs have ballooned in this area in Chapter 3 of Failed State, by Sam Freedman

Some people get more spent on their healthcare over their lifetime, after all.

This would also help to bring down the cost of some interventions, where costs have become inflated - as private providers would have an interest in ensuring they were within the new limits, such as healthcare is typically provided at a lower cost here than it is in the US.

Perhaps the educational equivalent of NICE could be called the National Association of Secondary and Tertiary Institutions (NASTI)?

I don't disagree that more of an evidence base would be very useful for making decisions about school spending. But I'd note that (1) class sizes in primary are now too large for any one teacher to accommodate different learning styles or pace of learning, which means unlucky kids can't learn unless they get extra help. (2) The curriculum requires all children to develop at the top of the bell-curve to thrive in primary school - too quick, you get pulled back into very boring "mastery"; too slow and you're left behind by the rest of the class with no accommodations unless you are diagnosed SEND and/or get an ECHP. And also (3) never forget that school spending (much like NHS spending) is a postcode lottery. You are very lucky to have what sounds like relatively easy access to Great Ormand Street. Those of us not in commuting distance of the best postcode for our ailment are still dying or becoming disabled because we weren't lucky enough to live in the right place.

Also, to what extent have you taken inflation / value of the £ into your calculations?