Raising taxes increases revenue but harms the economy

Note that I accidentally restricted comments on the Parenting Survey results to paid subscribers only. I’ve now made it for all subscribers, so if you’d wanted to comment but weren’t able to, now’s your chance!

Last month I posted about Seven Public Policy Rules of Thumb. By rules of thumb I meant things that aren’t always true, but are true a good sight more often than they’re not - and if someone tries to claim something that contradicts one of them, you’re allowed to demand extraordinary evidence before accepting it. They were:

The Laws of Supply and Demand apply

Raising taxes increases revenue but harms the economy

You’re more likely to hear about the outliers

Banning something reduces its prevalence, but not to nothing

Destigmatising something will make it happen more.

Claims which require heroic assumptions are probably false

Loopholes will be exploited

I got a good reception for this, but the one for which I received by far the most push-back was on (2) - and, interestingly, the objections came from both the right and the left.

I think it’s still true though - as a rule of thumb - and so I’m going to double down on it here, and answer some of the most common objections. Before we do that though, a reminder of what I wrote before:

The revenue raising part is obvious (though see below). The harming the economy is a little more subtle.

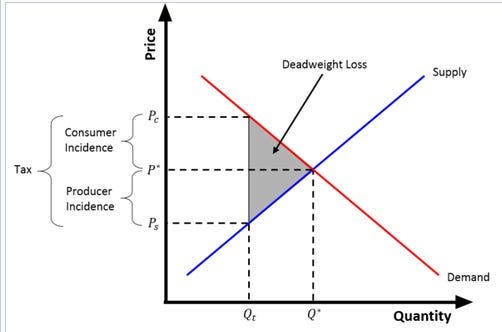

Tax introduces a ‘wedge’ in between the price that people are willing to buy something and the price that people are willing to sell something. In consequence, some trades that would take place don’t.

This applies to almost everything. Tax goods and some people won’t buy them. Tax services and people will use them less. Tax labour - for example via income tax - and some people will decide it’s not worth going out to work, increasing their hours or getting that promotion. Tax selling houses and people will move house less. Tax business activity and some companies will choose not to take a gamble on growth or expansion.

In the vast majority of cases these lead to a loss of economic activity. In the rare occasions where it doesn’t, it results in people forgoing something else they value, such as their beard.

Now, at this point, you are probably expecting me to mention the Laffer curve, and I will not disappoint you.

The Laffer curve says that sometimes the fall in economic activity is so great that imposing a tax actually results in less tax being collected.

The Laffer curve is real, but here’s the thing: in the vast majority of cases we are on the left side of the Laffer curve. Most times, increasing taxes increases revenue - it was never likely, for example, that the Government’s imposition of VAT on private schools would lose money, though exactly how much, net, it will raise, is a valid question. There are cases where we are on the right hand side - particularly if dealing with very wealthy, very mobile people with a lot of choices, or very high rates of taxation. But if someone claims that we are there, that’s one of those extraordinary claims requiring extraordinary evidence.

In most cases, the fact that increases taxes raises revenue but harms the economy is a good rule of thumb. The correct questions are how much, and to what extent.

Objections from the Right

Essentially all the objections from the right were that I hadn’t mentioned the Laffer Curve enough - or had underestimated how often it applied. Now I’ll say it again: the Laffer Curve exists, occasionally we’re on the right-hand side of it - and is probably even the case for some of taxes the current Government is imposing (such as the new taxes for non-Doms).

But usually, we’re on the left-hand side of the Laffer Curve. We are, right now, with the Employer National Insurance contributions, for example: these are harming growth (look at any business survey), but they are also raising revenue (billions of pounds of revenue to be precise). There are plenty of reasons to object to all sorts of taxes, but ‘they are raising net negative revenue’ is only occasionally one of them.

Unfortunately, it’s as if too many people on the right - and we shall name no lettuces - have memed themselves into believing that we’re almost always on the right-hand side of the Laffer Curve, and that therefore that tax cuts will pay for themselves, without having to cut public sector spending.

This matters, because it means the right isn’t doing enough of the hard thinking about how to reduce the size of the state, and where they want to reduce spending.1

Now this is absolutely possible: as I’ve written before, over the last 20 years Government has systematically extended the scope of the state2; in other areas - notably the state pension triple lock - they’ve repeatedly increased the rate of spending above inflation. And significant cuts are possible: Cameron cut spending by 5 percentage points of GDP over six years; Thatcher cut it by 8 percentage points over a similar period. But none of that happened by itself - and none of it happened just by cutting taxes. Only by cutting spending - significantly - can we get the lower tax society that many on the right3 want.

Objections from the left

Objections from the left were more varied - and some of them were smarter and more thoughtful.

On the other hand, some were not. A whole chunk of people made comments such as, ‘So, you think a country with zero public spending would have a good economy?’ or ‘If you wipe out the entire education budget that would be economically harmful.’

These people presumably also object to the physical law that the maximum efficiency of a steam engine is proportional to the temperature difference between the hot and cold reservoirs on the grounds that if you make it hot enough the metal that the engine is made of will melt. These are rules of thumb, not absolute laws, they are intended to work in most (not all) cases in a western developed economy - but sure, if you’re advising a mad dictator who thinks a sound economic policy is to cut all taxes to zero, I concede that you need something more robust than these guidelines to stop him.4

Various people observed that although you are taking money from the people you are taxing, you are spending it elsewhere. This is true, but this is where the Tax Wedge - that little grey triangle labelled ‘deadweight loss’ - is your bane. It’s the friction, the entropy loss, the fly in the ointment. In almost all circumstances5 you are losing some activity on the transfer - though designing your tax to make this deadweight loss as small as possible is definitely worth doing.

Some people raised the valid point that, in a recession, you can stimulate economic activity by the government spending more money - i.e. Keynsian Stimulus. However, they forgot that for a Keynsian stimulus to work, you need to be getting the additional money from borrowing.6 Raising taxes would choke off economic activity and counteract the stimulus. So Keynsian stimuluses tell us that government spending can help the economy; it doesn’t say that tax rises will.

On to more interesting objections, one person suggested that sin taxes were an exception, because the sins we wished to tax depressed economic activity. This, I’m afraid, badly overestimates the economic negatives of things such as smoking or carbon emissions.7 The thing that sin taxes have going for them is that we actively want to discourage that activity so the deadweight loss matters less. If we swap (to make up numbers) 10 units of tobacco-related activity for 7 units of non-tobacco related activity we might well consider that a win! But Rule 2 would still apply.

(As an aside, I can actually think of one sin tax that would probably break the rule: dynamic road pricing, because the economic costs of congestion are so high. Certainly switching out our current system of fuel duty and road tax for dynamic road pricing in a fiscally neutral way would be economically beneficial).

And finally, various people made the argument that a particular spending programme - apprenticeships, trains, mental health treatment - would boost economic activity enough to outweigh the deadweight loss. I’ll concede that if you are looking to find exceptions to Rule 2, this is the most fruitful area to look. But there are two snags:

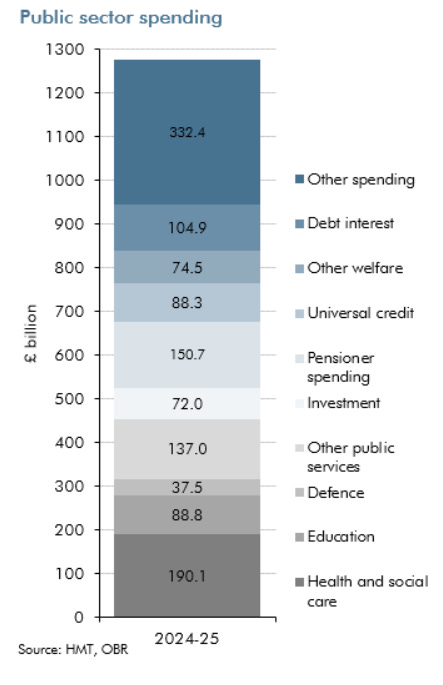

a) Almost no government revenue is hypothecated. New taxes just go into the general pot and are spent on the current spend profile - which as we’ve seen, has large sections going to health, welfare, pensions and so forth. In thinking about a new tax - as opposed to a new spending programme - it doesn’t usually make sense to assume it will all be spent on your particular growth-boosting priority.

b) People tend to vastly overestimate the *economic* benefits of their spending. I understand why, because it’s the game everyone has to play with Treasury, but it’s not actually true. Take health spending for example. Most health spending goes on keeping older people, no longer in the work force, alive. This is a great thing to do! But it’s not a huge driver of economic activity (beyond the spending itself). Similarly, defence spending makes our country more secure, but while it creates jobs, any spending creates jobs. Genuine investment in productive capacity - roads, railway, energy, machines - can boost the economy, but most spending isn’t in this category.

In short, just as some on the right have memed themselves into believing that every tax cut will pay for itself via Laffer Curvism, I worry that some on the left believe that every bit of public spending they support will pay for itself, via increased economic activity. This is equally unhelpful to good policy making: it is far better to think of most spending as buying something else we value - a better educated citizenry, culture, a more secure nation, a healthier population - but at a cost. And, frankly, if we believe in these things, we should be unashamed of justifying them on those terms.

So I’ll continue to defend Rule 2. Raising taxes, as a rule of thumb, increases revenue but harms the economy.

But I’ll end on a note of positivism. Sometimes it is possible to square the circle - and in this case, the name of that trick is called tax reform.

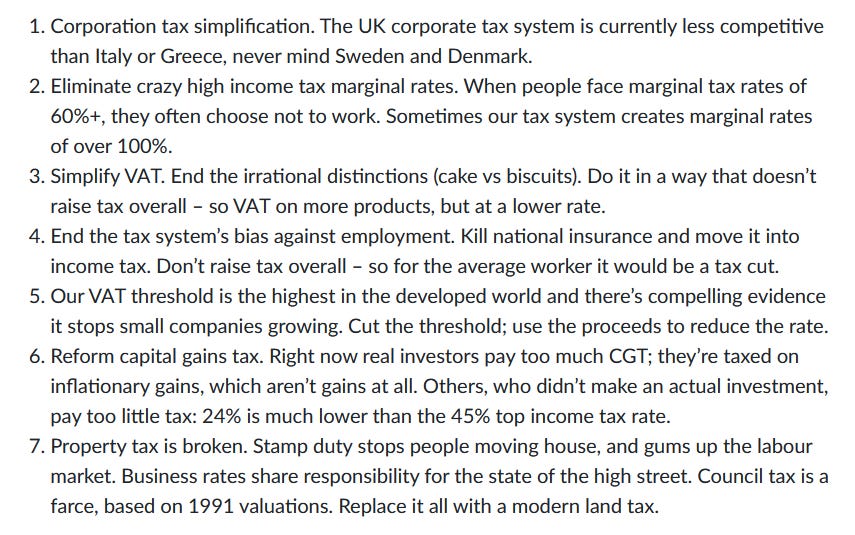

Our tax system in Britain today is overly complex and economically distortionary. We have weird cliff edges, economically inefficient taxes and a system ridden with weird exceptions that have grown like carbuncles over the decades. Our tax system is so bad that, when Labour party member and tax expert Dan Neidle proposes a list of fiscally neutral tax reforms, I can wholeheartedly support them - despite us being on opposite sides of the political spectrum:

Implement these fiscally neutral tax reforms and we’ll get greater economic growth - without losing a penny of tax revenue. And that quickly translates into both more money in our pockets AND more money for the Exchequer.

All it takes is a party willing to put it through Parliament.8

For a very recent example, they just expanded the definition of which children are eligible for free school meals.

Including me!

A double-0 agent with a license to kill might be a good start.

To repeat myself, the two exceptions I’m aware of are a poll tax, because people don’t kill themselves to avoid tax, and a true Georgist land tax, because you can’t change the amount of land there is. But the first is generally seen as inequitable and the second is very difficult to apply.

This is one of the rare occasions when Government borrowing is actually good. However, what most self-professed Keynsians forget is that Keynes also said the government should be paying down its debt outside of recessions, in order to be able to do the stimulus in the bad times.

At least in the short to medium term on carbon. With smoking, everyone dies of something and so cost the NHS something, smokers in particular tend to die at the end of a working life - in fact, the net impact on the Exchequer is likely positive (tragically) due to not paying pensions).

This is not as ridiculous as it sounds. Though radical, they would result in large numbers of winners as well as losers - and, more importantly, would lead to a stronger economy in a few years, meaning that if a Government did it after being elected, it could expect to reap the rewards by the time of the next election. This is the strategy - take the tough decisions early and they’ll pay off - is what Cameron pursued, and it worked.

Enjoyed the piece, thanks! Let’s hope we don’t have to wait too long for a party/leader to make the case for a programme like Dan Needle’s!

Excellent piece; I also read the original piece and agreed with much of it although I incline to the view that the law of supply and demand is more always than usually true. As for tax reform - indeed, it is long overdue. But it is a huge political and administrative challenge, because to do it right will tread on a lot of toes (another rule of thumb, which applies redoubled in no trumps for tax law: every special case in legislation is there because a well-funded and articulate lobby group got it put there) and I'm not sure it can be done without a manifesto commitment. I think it's election-winning though, if only we had any politicians other than Farage with the presence to lead rather than slavishly follow public opinion.