Seven Public Policy Rules of Thumb

They're not always true. But you've got grounds to demand strong evidence before accepting that one isn't.

If you’ve not yet taken my Parenting Survey, take it now - open for responses until Sunday evening.

You know the feeling when you’re debating an issue with a friend - tax, housing, abortion, marriage, the water companies, you name it - and you think you’ve both just got different perspectives or assessments of the trade-offs, when suddenly they come out with something that makes you realise you’re not just on different pages, but in a whole different library.

‘I don’t think people would buy less if the price went up,’ they say, calmly. ‘But nobody would ever do that,’ they protest, about an easily exploitable and highly profitable loophole. Or, ‘Banning it wouldn’t make people less likely to do it,’ they assert confidently.

These seven public policy rules of thumb are helpful guidelines for conversations like these.1 They are factual, not normative: in other words, they tell you about the world as it is, not the world as it morally should be. They’re not always true2 - but they’re true a good sight more often than they’re not, and if someone tries to claim something that contradicts one of them, you’re allowed to demand extraordinary evidence before accepting it.3

Here they are:

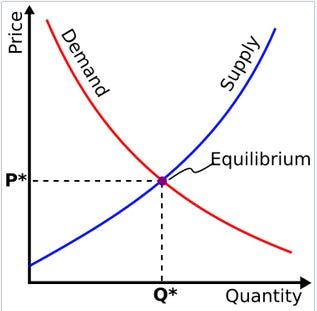

The Laws of Supply and Demand apply

Raising taxes increases revenue but harms the economy

You’re more likely to hear about the outliers

Banning something reduces its prevalence, but not to nothing

Destigmatising something will make it happen more.

Claims which require heroic assumptions are probably false

Loopholes will be exploited

The Laws of Supply and Demand Apply4

The laws of supply and demand are the most powerful tools in economics.

There are a number of implications, including:

If supply is greater than demand, prices will fall, causing demand to increase.

If the price of something rises, demand will fall.

If demand is greater than supply, prices will rise, causing supply to increase.

If the price of something drops, supply will fall.

A corrolary is that if something can be parsimoniously explained by the laws of supply and demand - such as the prices of flights rising in school holidays - other explanations - such as ‘price gouging’ - are less likely to be true.

The laws of supply and demand aren’t always true. Veblen goods exist, including Rolex watches and university courses.5 Giffen goods exist, theoretically, though are rarely spotted in the wild. But in most cases you can count on them.

Raising taxes increases revenue but harms the economy6

The revenue raising part is obvious (though see below). The harming the economy is a little more subtle.

Tax introduces a ‘wedge’ in between the price that people are willing to buy something and the price that people are willing to sell something. In consequence, some trades that would take place don’t.

This applies to almost everything.7 Tax goods and some people won’t buy them. Tax services and people will use them less. Tax labour - for example via income tax - and some people will decide it’s not worth going out to work, increasing their hours or getting that promotion.8 Tax selling houses and people will move house less. Tax business activity and some companies will choose not to take a gamble on growth or expansion.

In the vast majority of cases these lead to a loss of economic activity. In the rare occasions where it doesn’t, it results in people forgoing something else they value, such as their beard.9

Now, at this point, you are probably expecting me to mention the Laffer curve, and I will not disappoint you.

The Laffer curve says that sometimes the fall in economic activity is so great that imposing a tax actually results in less tax being collected.

The Laffer curve is real, but here’s the thing: in the vast majority of cases we are on the left side of the Laffer curve. Most times, increasing taxes increases revenue - it was never likely, for example, that the Government’s imposition of VAT on private schools would lose money, though exactly how much, net, it will raise, is a valid question. There are cases where we are on the right hand side - particularly if dealing with very wealthy, very mobile people with a lot of choices, or very high rates of taxation.10 But if someone claims that we are there, that’s one of those extraordinary claims requiring extraordinary evidence.

In most cases, the fact that increases taxes raises revenue but harms the economy is a good rule of thumb. The correct questions are how much, and to what extent.

You’re more likely to hear about the outliers

You’re more likely to hear about something if it’s unusual, surprising or otherwise shocking. People are more likely to share it on social media, news sites are more likely to cover it prominently (or indeed at all) - and you’re more likely to take time to stop and read about it.

To give specific examples, you’re more likely to hear about a month when the Government borrowed a record amount, or where growth was surprisingly low (or high) than one where things just toodled along normally. You’re more likely to hear about an outlier poll where Reform gets 35%, or Labour under 20%, than the normal polls where they’re bobbing about at 30% and 23%.11

To counter this, firstly, be aware that it happens. Know that individual figures by themselves - a single month’s economic statistics, a single poll - are not that reliable. And if it’s a subject you’re interested in, develop sources (such as a poll aggegrator, or ONS or OBR stats) which can give you a more comprehensive view of the numbers you care about, that you can check one-off results against.

Banning something reduces its prevalence, but not to nothing

If you ban something, its prevalence will drop. Most people obey the law, either through natural law-abidingness, or through fear of getting caught and being punished. How much it will fall will depend on a variety of things, including how much people want to do it, whether there are alternatives that can substitute for it, cultural issues and both the likelihood of getting caught and severity of punishment.12

Banning something rarely completely eliminates it.13 It’s reasonable to observe that, if something is banned, the circumstances in which it still happens may be worse. For example, the Government may no longer be able to tax it (if smoking was banned), or women might do it in less safe conditions (if abortion was banned).

These are not, in themselves, reasons not to ban something. As in so many of these rules of thumb, what matters is how bad the thing is, how much it drops, and how bad (viz a viz it being legal) the downsides of it continuing to occur illegally are.

One confounder here is that different people often disagree about whether something is bad in the first place. Let’s imagine two people who oppose cannabis being illegal. The first thinks smoking cannabis is harmful, but that banning it won’t reduce the prevalence much, and is outweighed by the loss of tax revenue and the flow of revenues to organised crime. The second just doesn’t think smoking cannabis is harmful. Or, if you prefer, substitute cannabis with abortion, or pre-marital sex, or smoking, or smacking children.14

Those in the second camp may use arguments from the first, hoping to win over those who disagree with them on the fundamental point of whether the thing in question is harmful. This is totally sensible as a persuasive technique, but it can make it hard to tell whether you’re disagreeing with someone about the fundamentals (‘Is X harmful?’) or the trade-offs (‘are the downsides of banning X worth the gain?’). One key ‘tell’ is whether or not someone is genuinely weighing up the trade-offs or not.

Destigmatising something will make it happen more.

The mirror of rule four: destigmatising, or celebrating something, will make it happen more often. Be wary of anyone who argues for ‘destigmatisation’ without taking this into account.15

The arguments that ‘stigmatising taking drugs stops some addicts getting help that would make them better off’ and ‘stigmatising racism means some people don’t take actions they should for fear of looking racist’16 are both arguments of the same form. Depending on your politics, you may be more sympathetic to one of them and the other. But both ignore the fact that if we stigmatised taking drugs less, more people would take drugs, and if we stigmatised racism less, more people would be racist. And these are both bad things.17

You know the drill by now: the right amount of stigmatisation is a trade-off, balancing the harm that comes from stigmatising, with the harm that would be done by not stigmatising. Anyone who won’t acknowledge the trade-offs isn’t arguing seriously.

Very occasionally, we get to do an end-run around the whole problem and to have our cake and eat it.18 A great example of this is teenage pregnancy, where we figured out that having good sex education and providing contraception reduces the prevalency enough that the previous dynamic was no longer relevant.19 But usually, it’s trade-offs all the way down.

Claims which require heroic assumptions are probably false

If someone claims something, consider what it would actually take for it to be true. If that requires heroic assumptions, then the claim probably isn’t true after all.

Let’s consider three commonly made assumptions

Private schools provide no better education than state schools.

Sending people to prison doesn’t reduce crime.

Men and women are equally attractive.

Let’s look at these in turn.

In 2022-23, private school fees, after deducting bursaries and scholarships, were almost double the cost of the funding per pupil that state schools receive (£15,200 vs £8,000). Now, I’m sure that private schools are spending some of that money on pointless but impressive looking facilities that don’t make much difference to education - and money spent isn’t the biggest driver of education - but seriously, you’d have to try pretty hard to spend £7,000 per pupil per year and not have it improve education in any way.

When people are in prison, they are not committing crimes.20 In fact, a relatively small number of hyper-prolific criminals commit a very large proportion of crimes. If it was true that prison didn’t reduce crime, we would have to assume that, when we sent people to prison, the rest of the population started committing crimes at exactly the same rate to account for the difference.21 Given that’s probably not happening, the claim is probably false.

Women, on average, spend a lot more time and a lot more money trying to make themselves look attractive than men do. Now, maybe some of this time and money is wasted buying weird ugly clothes that fashion editors said are ‘in this season’ or doing strange things to their eyebrows that only other women who care about fashion notice or care about.22 But to believe that men and women are equally attractive, we’d have to believe that ALL this time and ALL this money was wasted, which seems pretty unlikely.

People often resist obviously true statements because they get them mixed up with cognitively adjacent statements that may not be true, because they worry they imply a normative claim, or because it offends some sacred value. But none of these make the first statement false.

Some people may believe strongly that teachers at state schools have a tougher job, or use better teaching techniques, than those in private schools. Others - from both directions - may worry about what a claim that the education is better in private schools implies about university admissions. And still others may think that private schools are unfair or immoral. All these points are valid. But none actually contradict the first proposition.

Some people may think that even if prison cuts crime, it’s not cost effective. Or that it needs to do better at rehabilitation, or that it is not humane. Again, all valid perspectives - but none mean that criminals behind bars aren’t committing fewer crimes.

Some people may feel that any observation of differences between the sexes contravenes the sacred value of equality, or seems sexist or patriarchal, or might imply that people should act in a certain way they disagree with. All valid, once again - but none that should make us doubt that if one group of people (on average) spend much more time and money trying to do something than another, the first group are likely to get better results.

We shouldn’t let the true statements smuggle in the secondary statements or normative positions without scrutiny. But neither should disagreeing with cognitively near statements make us reject true propositions.

Loopholes will be exploited

Love always finds a way, water always flows downhill - and people always, always, find ways to exploit loopholes.

Whether it’s men going to the trouble of training as priests or scoutmasters to abuse children, or big companies setting up the double Swiss Dutch variant Irish sandwich23 to avoid tax, to a whole host of more innocuous examples, people will find and use loopholes.

Culture can protect you a bit here: most people obey the law, and some things may just be ‘not done’. But the clue here is ‘most people’ - and if something is actually legal (or if there is no means of enforcement or checking) then, sure as certainty, someone’s going to make use of that sooner - or later.

Beware the person who says, confidently, ‘but no-one would ever do that’. Or even worst, ‘no-one [of a certain sort of person] would ever do that.’ Maybe they wouldn’t do that. But some people would.

As with many of these guidelines, there’s room for a discussion about how many people would, what the consequences are and whether the enforcement is worth the candle. But if there’s a loophole, someone will take it.

And a reminder, if you’ve not yet taken my Parenting Survey, take it now - open for responses until Sunday evening.

And no, I promise, they’re not all just restatements of the laws of supply and demand.

And I will give some examples of the times they’re not.

Yes, random blog writers are allowed to set rules for debates, that is how the world works, just like how if you’re really really really good at anonymous blogging you get elected to be world president.

I said not all of them were going to be the laws of supply and demand, not that none of them would be, OK?

At least if the price is capped at levels such as in the UK.

Maybe one and a half of them are about supply and demand?

The two exceptions I’m aware of are a poll tax, because people don’t kill themselves to avoid tax, and a true Georgist land tax, because you can’t change the amount of land there is. But the first is generally seen as inequitable and the second is very difficult to apply.

To give a specific, if niche, example: one thing that deters me from making this a paid substack is the amount of tax I’d pay. I value both money and readers, and tax means the amount I’d have to earn to make up for the lower readership on some articles is considerably higher.

I think that both beard taxes and window taxes would actually promote economic activity, as people got themselves shaved and paid people to block up their windows.

The Government’s treatment of non-doms, for example, may be such a case.

I realise to anyone who’s not been following polls since the general election that the ‘normal’ numbers look a bit odd here but yes, voter intentions are that extraordinary at the moment

.

In most cases, people respond more to the likelihood of getting caught than the severity of the punishment.

Even murder, with strong moral prohibitions against it and steep punishments, still happens.

Again, as with the previous rule, a confounder is that many of those who argue for destigmatising something don’t actually believe it is bad in the first place.

There’s a strong argument that by destigmatising mental illness - something that sounds unequivocally good - we’ve dramatically increased its prevalence, in a way which is very very bad. It may well be that as a society we’ve not found the right balance on this yet. See for example here, here or here.

And to both have, and eat, two metaphors for the price of one.

This is one of the rare social problems that we have effectively solved between the time when I was in school and now.

Other than crimes against other prisoners.

In some very specific cases, if you take out some criminals, others may take their place - for example, if you took out a Mafia gang, other gangs might move into their territory. I imagine drugs might work quite like this. But most crime is not like this.

At this point you may notice I know less about fashion than I do about policy and economics.

OK, I made this one up.

The only point I would add to your notes is to include a mention of David Friedman's "Hidden Order: The economics of everyday life". As a physicist, I found it really useful for understanding economics, perhaps because Friedman also has a background in Physics and so he explains it in a way that makes sense to me.

Number 7 is a particular annoyance to me and is a red flag in a conversation, indicating that the person I’m speaking with doesn’t really understand their fellow humans.