Parenting Survey: Results

What do my readers really think about bringing up children?

Firstly, a little follow-up from recent posts. I was delighted by the reception that Seven Public Policy Rules of Thumb received, and particularly pleased when it was featured in the Financial Times by the inimitable Stephen Bush. We’ll be returning to say a bit more about Rule 21 - on which I got the most push back from both left and right - in the next post.

Secondly, I’m also pleased that my preferred candidate, Lord Smith of Finsbury, was elected Chancellor of Cambridge. To everyone who read my post here and voted as recommended - thank you, we did our bit!

But now on to parenting! Thank you to the 321 of you who completed my Parenting Survey - my highest response to a survey yet! And particular thanks to everyone who shared it outside the core subscriber readership list.

The results are below - plus there’s an annex at the end about how I tried to use AI to analyse the results and it failed miserably at it.2

First, this was a self-selected survey, not a representative sample of the population, and should not be quoted or referenced as if it were. Respondents were:

57% male, 41% female.3

68% left-wingers, 23% right-wingers, continuing my theme of getting a disproportionately left-wing respondents.4

23% attended religious worship at least once a month, 76% didn’t.

Almost half (48%) had their first child in the 2010s or 2020s, 30% in the 1990s or 2000s, 4% in the 1980s or earlier, and 17% didn’t have children.5

Part A: Hopes and Fears

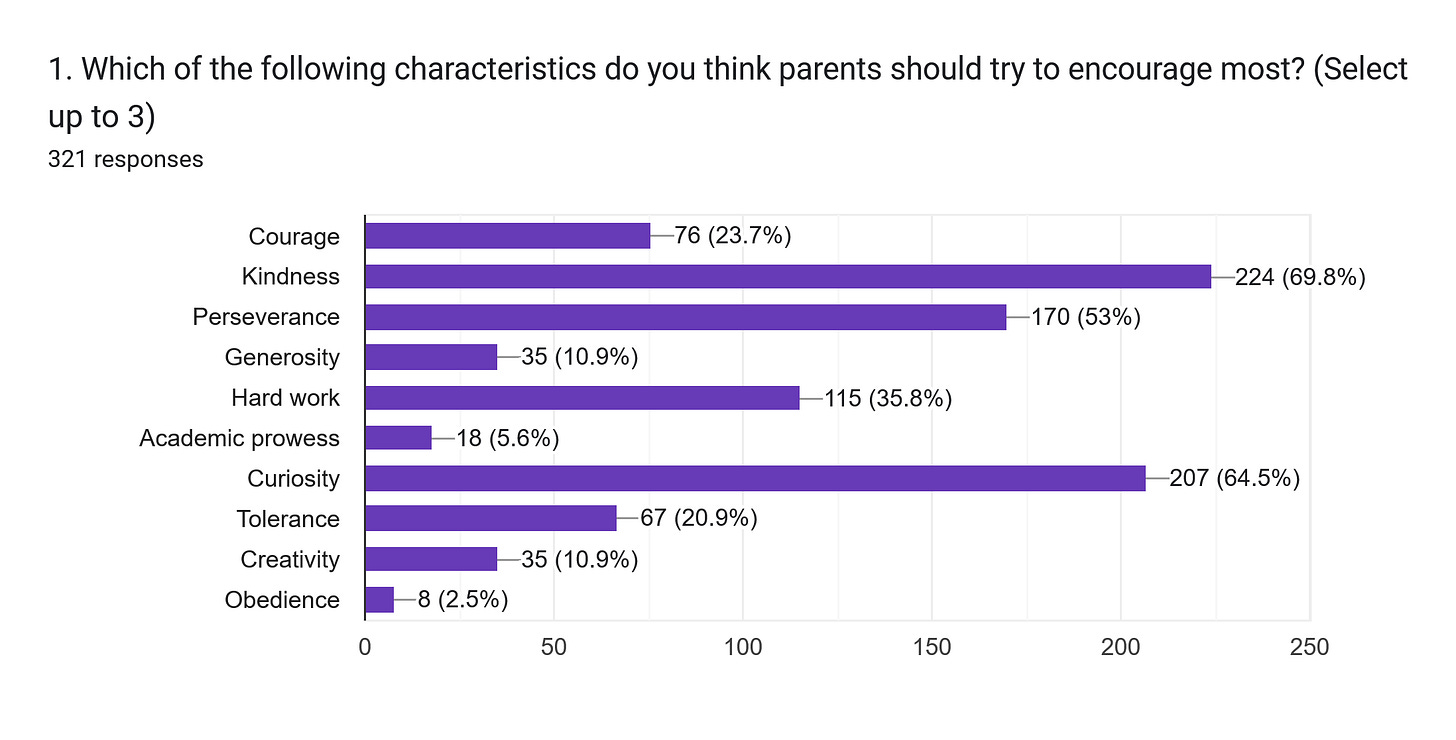

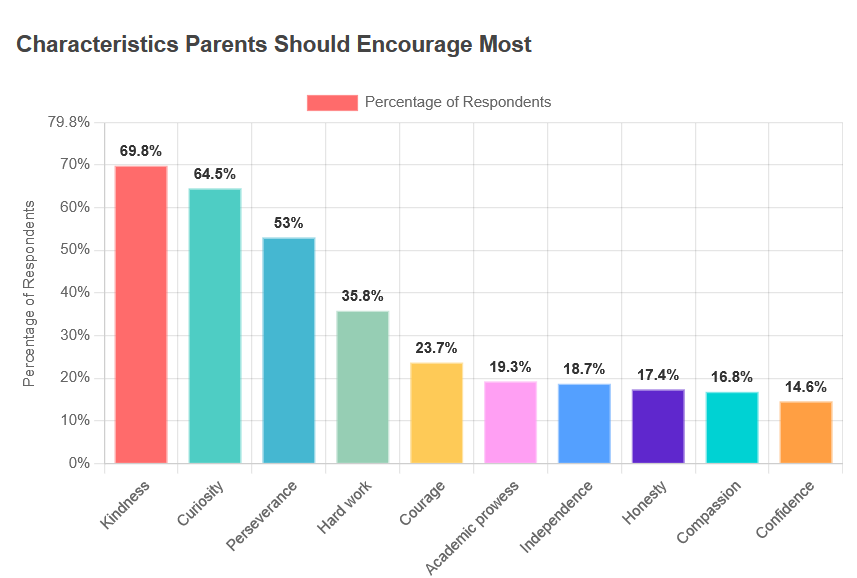

Kindness, curiosity and perseverance are the clear winners.

There’s no substantive male/female divide, but when we sort by political opinion, most values are very similar, including the order of the first three (though right-wingers marginally prioritise curiosity and left-wingers kindness), but courage is much more important for right-wingers: 43% vs 18%, and tolerance for left-wingers: 28% vs 3%.6

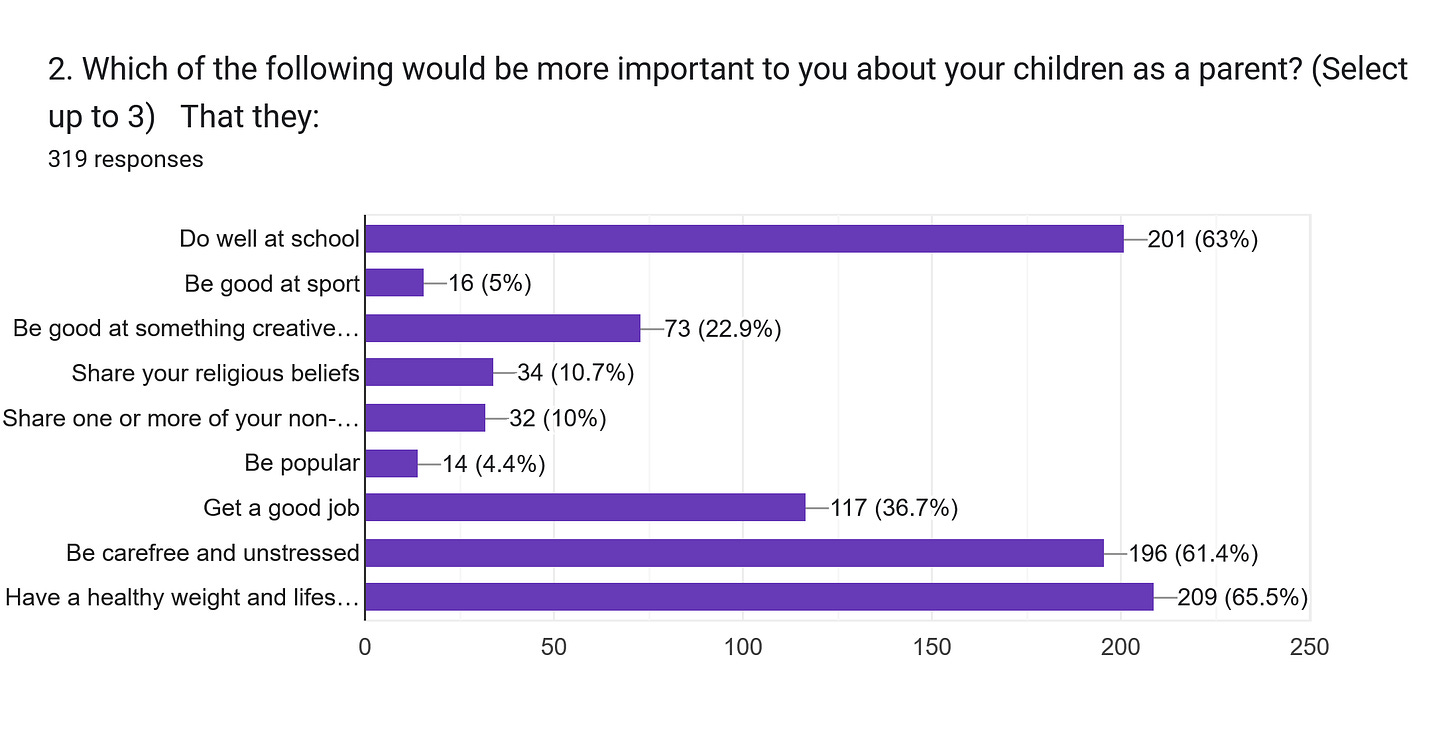

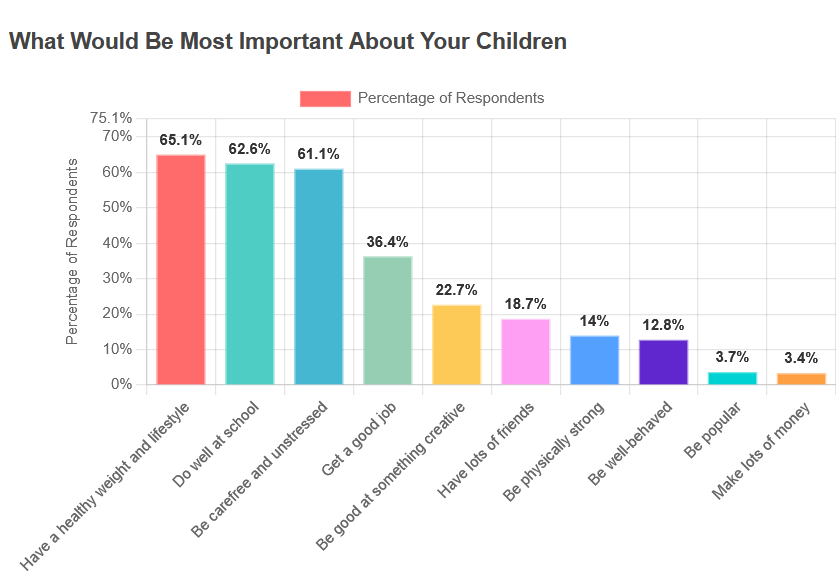

A very high importance is placed upon being healthy, carefree and unstressed. Interestingly, although in ‘traits’ academic prowess came near the bottom, ‘do well at school’ was selected by two-thirds of people, suggesting that it’s all in how you ask the question!

Unsurprisingly, people who attended religious worship at least once a month put a much higher priority on their children sharing their religious beliefs, with just over half putting this as a top priority.

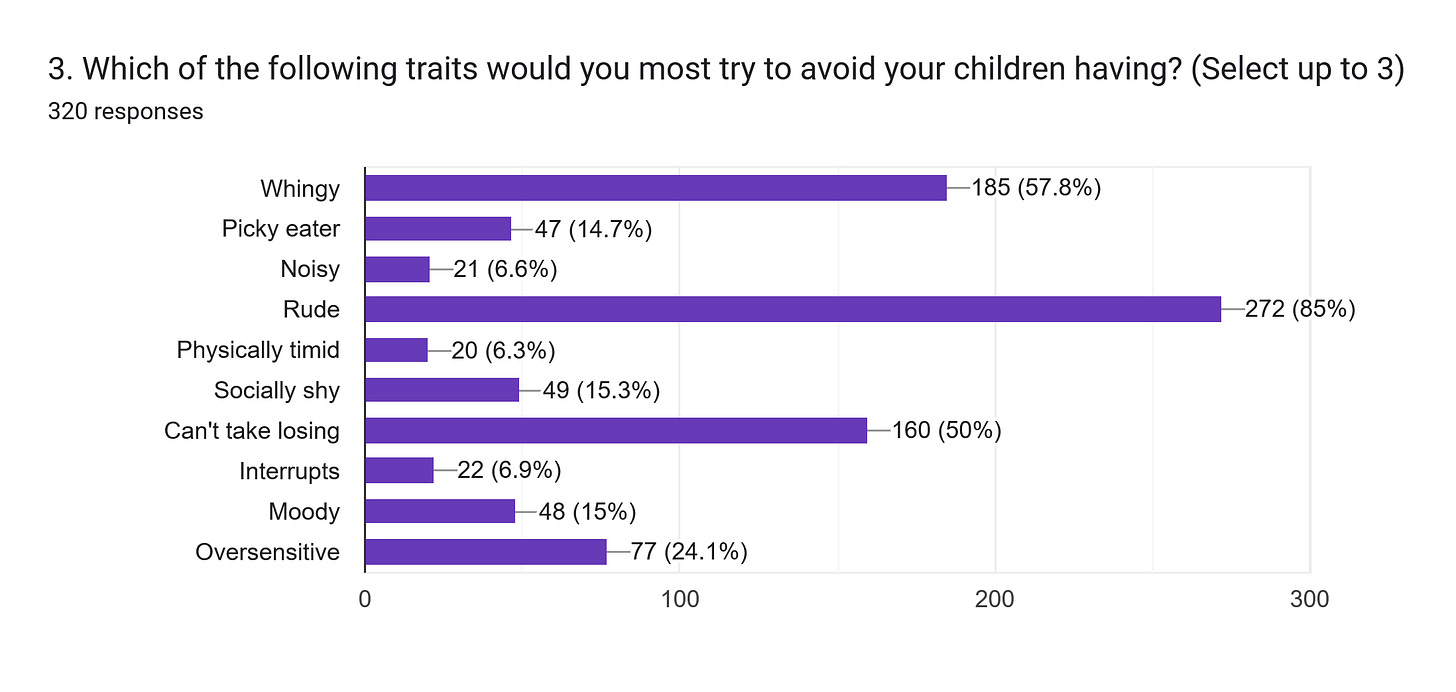

I am fully with the respondents here, as whingy and can’t take losing were two of my selections, though I also chose my personal bugbear of ‘picky eater’.7

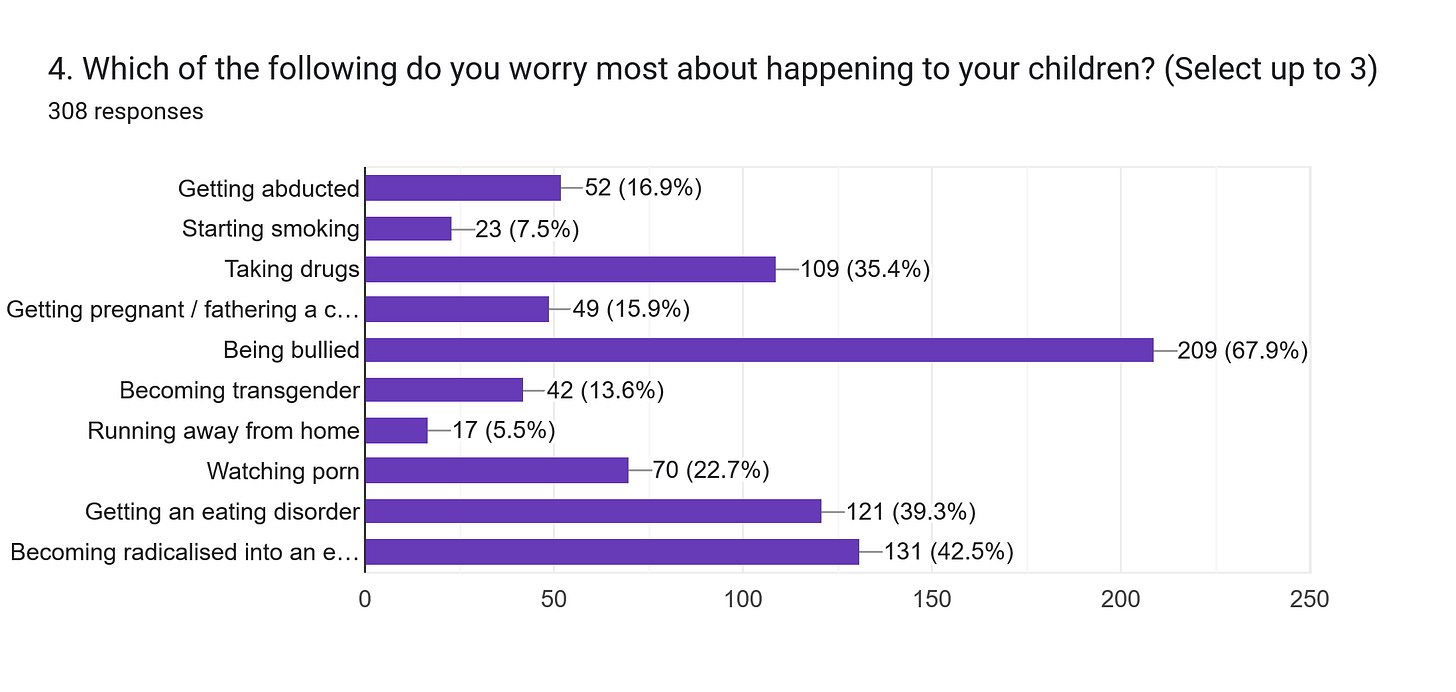

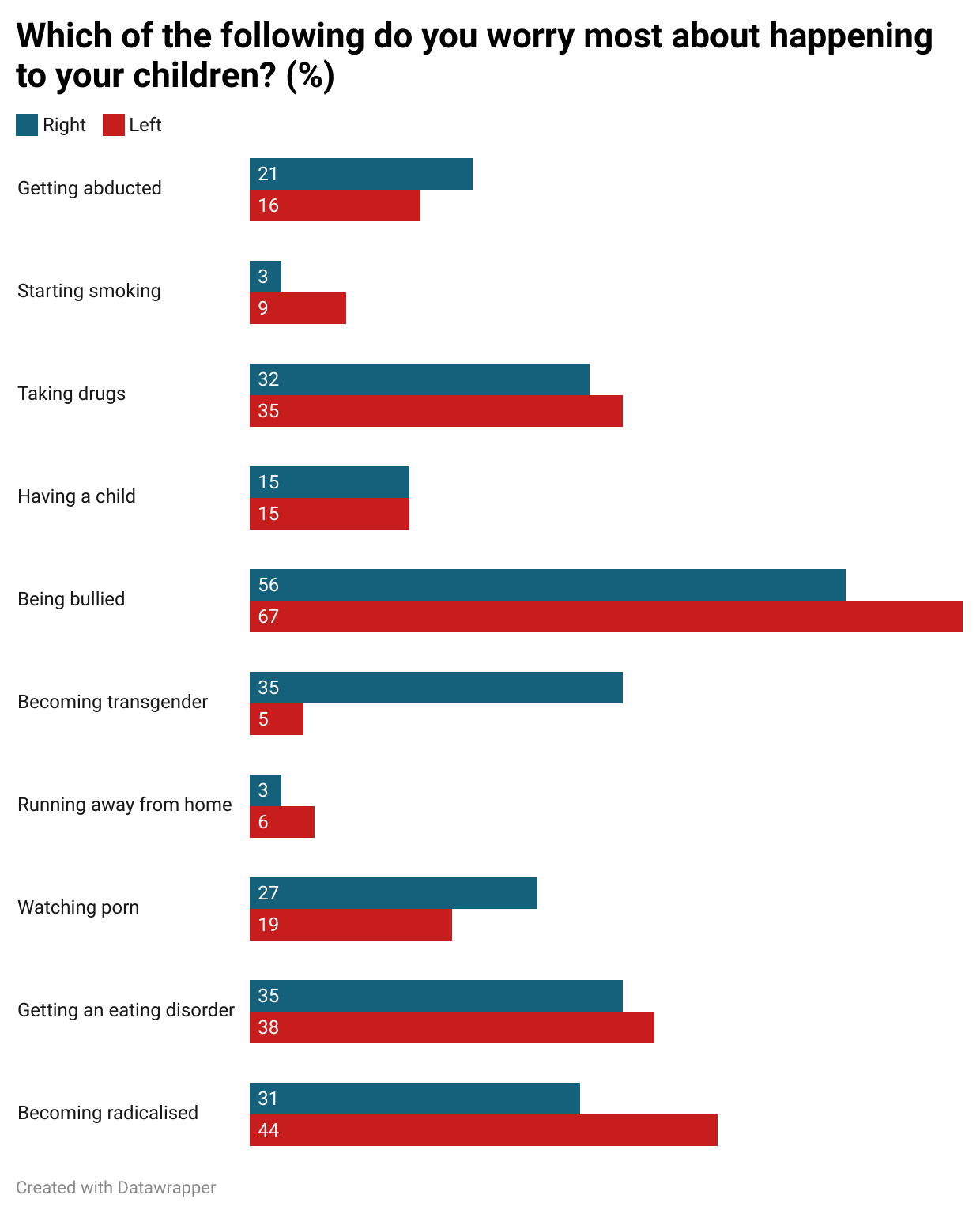

This is pretty encouraging in that I have a readership who can assess both severity and likelihood when evaluating risks, as shown by ‘being bullied’ coming out top! I do wonder if smoking would have been higher a generation ago - it has declined so much.

There are some interesting cross-breaks here. Women are almost twice as likely as men to worry about their kids watching porn8 but, interestingly, less likely to worry about them getting an eating disorder, which I wouldn’t have predicted.

The big difference, though, comes with the left-right split

Drugs, eating disorders, parenting a child (interestingly!) and abduction are pretty similar, and both have bullying as their biggest worry. But over a third of right-wingers (vs just 1 in 20 left-wingers) worry about their child becoming transgender - which should put some perspective on the debates about RSHE and other teaching in schools: for many on the right, schools are simply not safe spaces for their children, but rather the authorities a source of danger. Conversely, left-wingers worry significantly more about their children being radicalised.

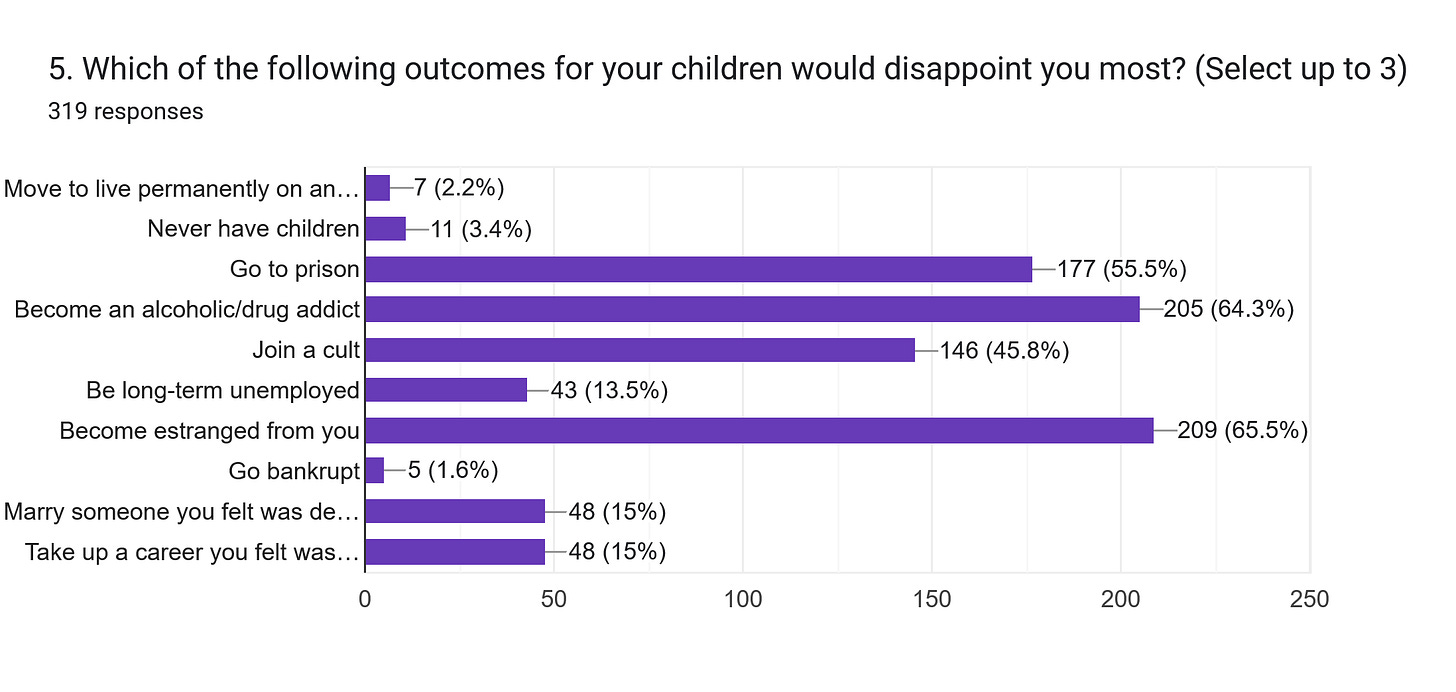

Finally in this section, we looked at what would disappoint people most9:

Becoming estranged is the biggest worry, with those that most harm your life - addiction and prison - next. I was surprised to see bankruptcy so low, as well as ‘never have children’ - but perhaps the desire for grandchildren starts later!

Part B: Judgy, judgy!

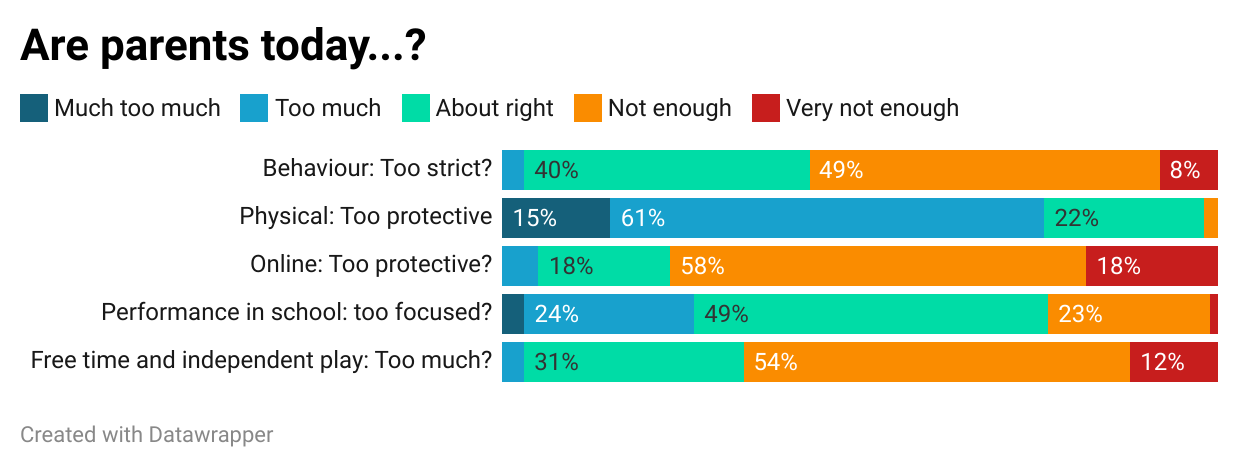

Here I asked respondents to think of the typical parent today, and to judge their behaviour:

Here, we meet expectations: in general, people think parents today are not strict enough, too protective in the physical world, not protective enough online and don’t give their children enough independent play, and are probably about right in terms of how focused they are in school performance (or at least, half do, with even breaks either side).

I think all these things too, so I would like to congratulate survey respondents for having the best opinions! Please keep reading this blog, so I can keep having readers readers like you who agree with me. :-)

Cross-breaks here generally conform directionally to stereotypes. Lefties are more likely than righties to think parents are about right on behaviour (but half still think they are more lenient and almost none think parents are too strict), men very slightly are more likely than women to think parents are overprotective - but none of this is enough to shift the overall patterns.

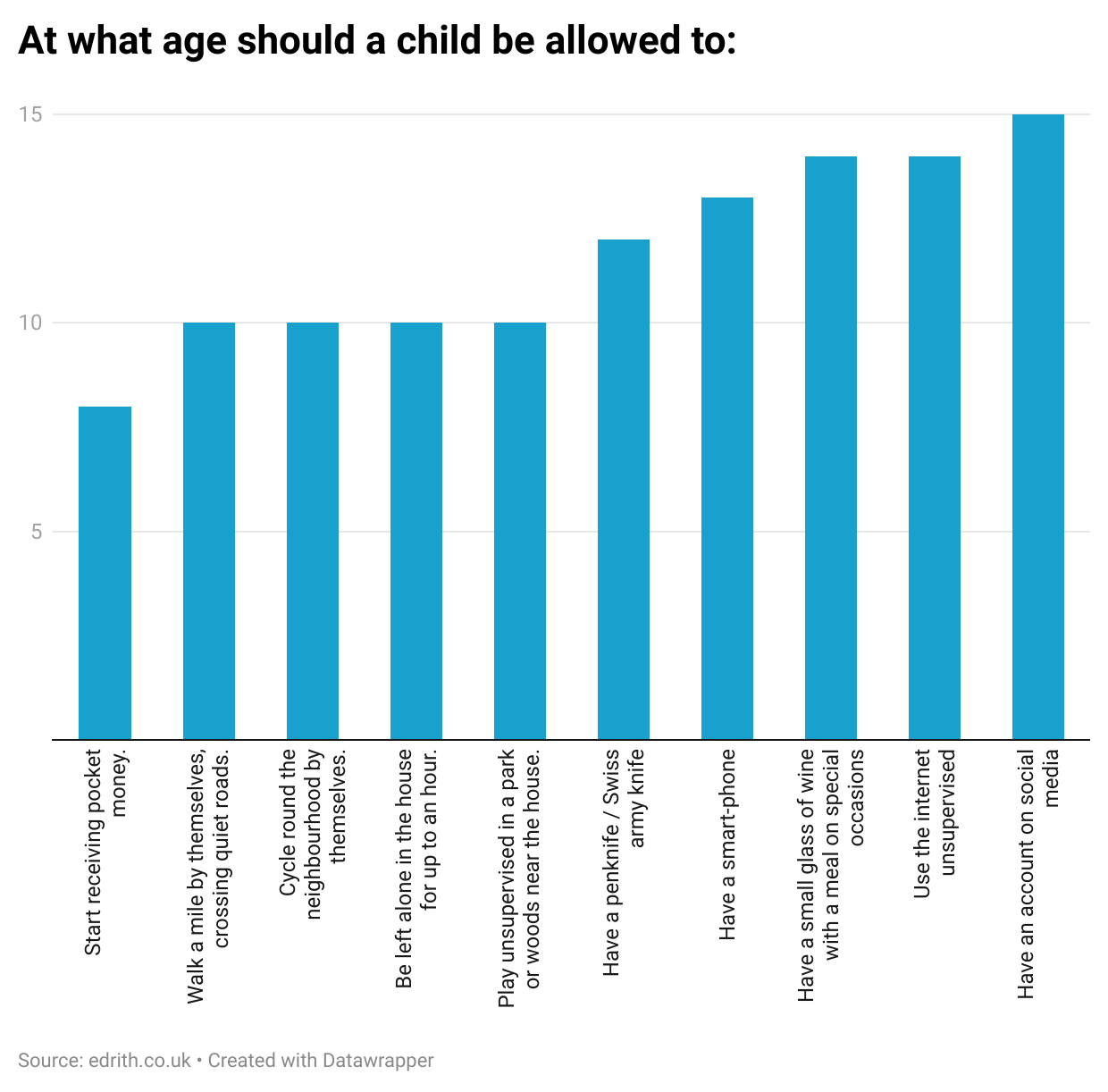

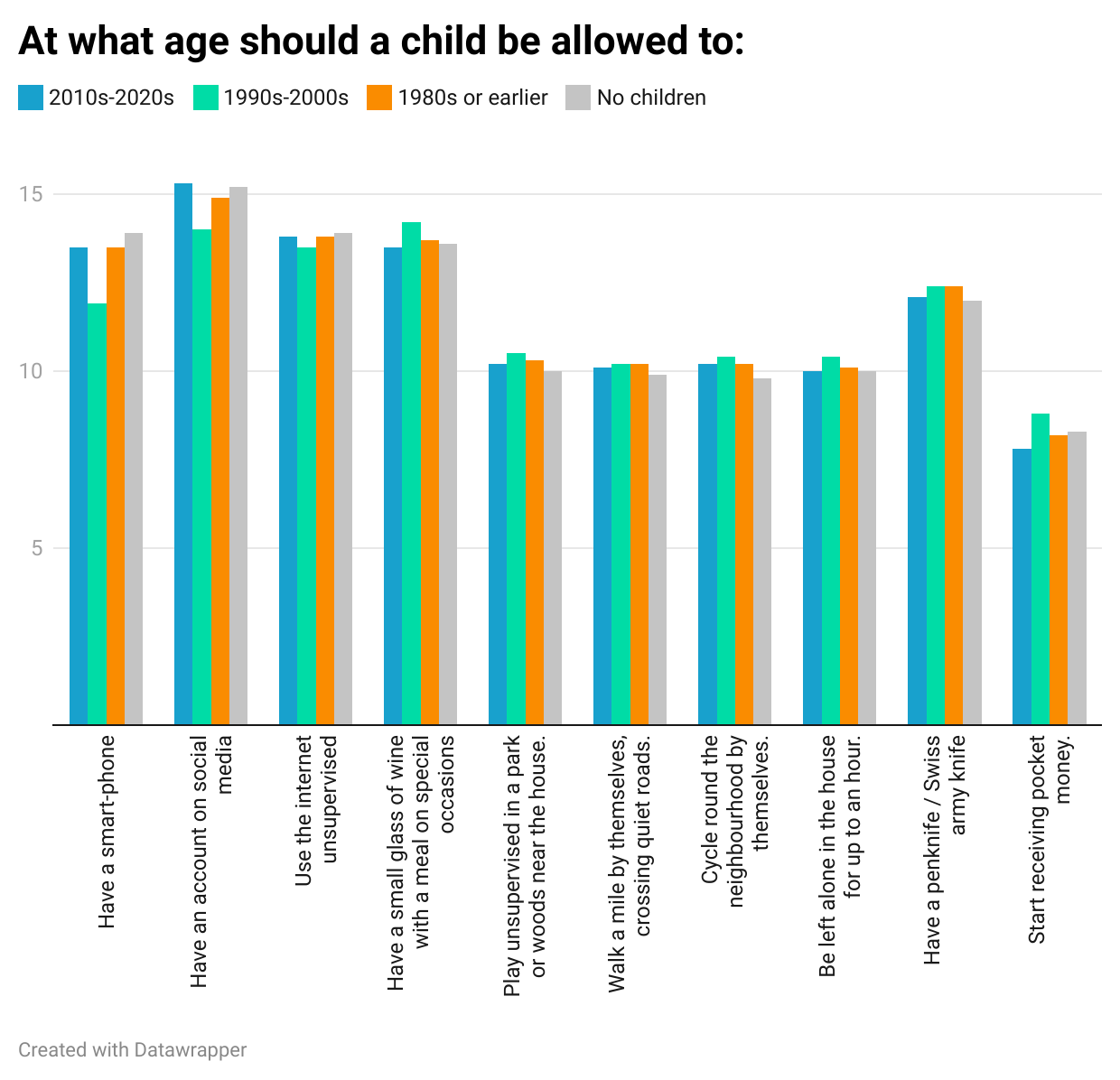

Part C: Age Limits

I was particularly interested in if there would be generational changes here, or between parents and non-parents, but we don’t really see that. The one trend of note is that 1990s - 2000s parents appear to be a little more permissive on digital things, and (very) slightly more cautious in the real world - perhaps reflecting the less ubiquitous internet of that period.

Part D: Helpful or Harmful?

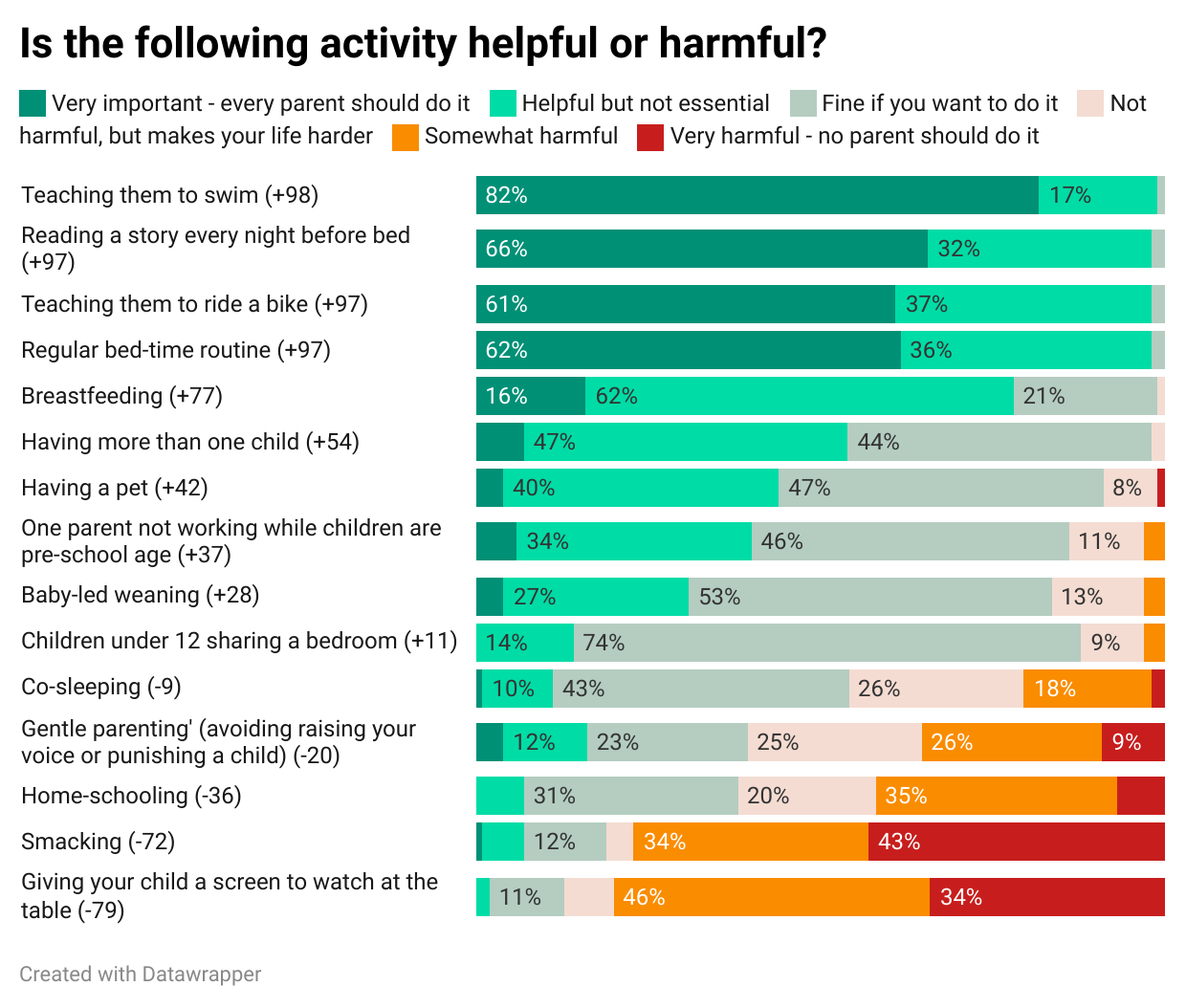

Here I was curious as to whether people thought certain activities - from the controversial to the mundane - were helpful or harmful.10

No surprise that people think it’s good to read to your kid and bad to give them a screen to watch at the table. I would be fascinated to see how the extremely high importance given to riding a bike and learning to swim translates across to other developed countries: I mean, we also have made sure our kids can do these things, but it definitely feels more culturally dependent than, say, ‘helping them learn to read’.

People were pretty relaxed either way by a good chunk of items, including co-sleeping,11 baby-led weaning and bedroom sharing. I was surprised at how many people thought having a pet was helpful.12 I assume that the couple of people who think it is ‘very harmful’ are going on some kind of safety or allergy issue, though presumably there is a difference here between a rottweiler and a gerbil.13

I was also, more substantially, surprised - particularly given the mainly left-wing respondent base - by the strong net support for one parent not working while children were pre-school age. Again, this is something I also agree with, but it is strongly counter-cultural, flies in the face of the cross-party consensus on Government policy and is the sort of thing that politicians or celebrities would get yelled at if they said it. A great example of a case in which public policy and the Overton window is dominated by an unrepresentative group of ‘Anywheres’ against public opinion.14

Unsurprisingly, a lot of people oppose smacking and home-schooling, though people are less intolerant of the latter than the former. I was surprised to see significant net opposition to ‘gentle parenting’, given it’s one of those things (like baby-led weaning) I hear promoted endlessly. There were also some active supporters of these, in all three cases.

Crossbreaks were as one would expect: people on the right were much less anti-smacking than those on the left (-20 vs -81); those on the right are also much more opposed to gentle parenting: (-48, vs -7 for those on the left). Those who attended religious worship were less likely to be opposed to home-schooling (-12, vs -42 for those who didn’t). Men were a little more likely to be pro breast feeding15 and anti cosleeping,16 but not by a huge extent.

A Final Word: Shared Priorities and Inconsistencies

As we all know, it’s safer to weigh in on Israel and Palestine or the Trans debate than it is to criticise another person’s parenting decisions, so I’m going to be cautious here. I’m very grateful for everybody sharing their views, and I genuinely believe that almost all parents are trying to do the very best by their children, that this is a tricky area, and that - particularly as society and culture changes around us, and every child is different - there is a great degree of uncertainty in many areas about what the right thing is to do.

However, there were a couple of areas of inconsistencies, as well as some areas of common ground, I wanted to comment on.

Firstly, there were quite a few people who thought that parents today were too lenient when it came to behaviour, but who also said that they thought ‘gentle parenting’ was very important or helpful.17 I checked to make sure this wasn’t a weird statistical artefact and yes, a non-trivial number of people had answered this way. Again, no shade on those who genuinely believe we should all be much less strict on parenting and follows through on this to its logical conclusion. But if you are someone who believes that parents today are typically too lenient, then I would very gently suggest that you may wish to reconsider your support for ‘gentle parenting’ and similar approaches.

Secondly, there were a chunk of people who felt parents were generally ‘about right’ in terms of how protective they were online, but then put ages 14-16 for when children should be allowed a smartphone, allowed unsupervised internet access or be allowed on social media. I think this may be a case of people not realising how prevalent some of these things have got: Ofcom says a quarter of 5-7 year olds have a smartphone and that most acquire one between 9 and 11, while other reports show large numbers of children on social media, using the internet unsupervised or being exposed to porn at surprisingly young ages.

Still on this subject, but moving on to areas of consensus, over three-quarters of us worry parents are not protective enough online - and, if we have children ourselves, this is presumably something that we worry about ourselves.18 As Jonathan Haidt says, this is about norms as much as laws, and there is a real collective action problem: if all of your child’s friends have smartphones at 11, it’s much harder to say ‘no’ to them, not just because of peer pressure, but because there is a real consequence that they may be left out of groups and messages where friendships develop and offline activities are planned.19

There is a lot that can be done here to build phone-free communities and shared norms. There are alternatives - ‘brick phones’, for example, or we have something called a Karri (essentially a glorified walky-talky) - for those who want to keep in touch with their children without giving them access to the internet or social media. Smartphone Free Childhood has brilliant resources and guides, both for use in your own life and to help talk to organisations such as schools. Already, in our own communities and neighbourhoods we can feel things shifting compared to just five years ago, with ‘not giving your child a phone as they start secondary school’ now feeling like a ‘normal’ minority position, rather than something that marks you out as very odd20: several parents on our street are not doing this, most primary schools in our town are going phone-free, and phones are strictly banned on things such as Scout camps.

And finally, in terms of the physical world, over three quarters of us think that parents are too protective and don’t give their children enough independence.21Cartoons Hate Her has written brilliantly about how this ‘safetyism arms-race’ occurs:

Basically, the arms race has four (maybe five) phases:

Phase 1: the most neurotic, safety-conscious parents are worried about something. They might even have legitimate reasons to consider an activity risky, but they’re not balancing the risk with the reward, or considering the overall implications. For example, no child has ever died because they couldn’t go to a sleepover. Therefore, banning sleepovers makes sense given that bad things sometimes happen at sleepovers.

Phase 2: the safety-conscious but generally reasonable parents start catching on. They hear about people who are more concerned about their children than they are, and they hate the idea of being the idiot who lets something horrible happen out of convenience. They wonder if the crazies know something they don’t know. They start wondering if perhaps it makes sense to ban sleepovers too, because maybe the ultra-uptight parents aren’t so crazy after all (or maybe they’re overstating the risks, but is the benefit strong enough?)

Phase 3: The general public buys in. Once a good 20% of people are banning something, it starts looking reckless to take part, especially if the activity doesn’t carry enough benefit to seem “worth it.” Some parents quietly allow the activity, but many parents decide that maybe the activity just needs to die. For example: no more sleepovers, it’s enough to just have an evening playdate.

Phase 4: The activity isn’t fully criminalized, but we’ve gotten to a point where a minority of parents are doing it. Parents will judge you for doing it, and they might even call CPS. Even if CPS has no legal authority to do anything about it (and finds the call to be a time-wasting nuisance,) a call to CPS is enough to terrify parents. Even if you’re a parent who thinks it’s fine, you go along with the majority opinion because you don’t want any drama.

Phase 5: The activity is made illegal, or at the very least, nebulously included under the umbrella of child neglect.

But here there’s an additional factor beyond the peer pressure and the social stigma - it’s that it’s scary! As a parent, it’s hard to let your child out of your sight, or to watch them climbing a tree up to some hair-raising height, and so on. I can remember the first time we let our son cycle a mile (on the pavement, and crossing quiet roads) To Tesco and back by himself - he was 7 at the time - I was counting the minutes to when he ‘should’ be home and had to stop myself from going down to the end of the road to watch him - he was fine of course. But it’s hard. And, of course, if they are playing physically, there’s a decent chance that at some point they will fall out of a tree and break their arm and similar, and it’s difficult not to overreact to this.

For me, as a parent, there are three principles I’ve found helpful in overcoming my instincts, that hopefully may be for others in similar situations.

Do enough that it’s uncomfortable. When discussing Christian giving, C. S. Lewis said there is no fixed amount to give, but it has to be enough that it is uncomfortable.22 I believe that in today’s world, with its culture of safetyism,, a very similar principle applies to children’s independence. Unless you are giving children enough independence and freedom and risk that you, as a parent, in some areas feel uncomfortable, and can feel that clutch in your stomach over whether they will be OK, you are probably not giving enough.

Don’t overreact to accidents. If you are letting children climb trees, ride bikes and play in the woods by themselves then they will have accidents. They will cut their knees, break their arms or get lost. You knew the risks before hand and they have not changed afterwards.23 It is very easy to overreact to that activity and say ‘ah, they must never climb *that* tree again’ or ‘never play in *that* area of the woods’ or ‘never do *that* activity again’. Occasionally this is justified - but far more often, it’s just the availability heuristic leading you to faulty conclusions.

Don’t create a culture where safety is all important. If you always emphasise safety and risk, your child will too. Of course, teach them to take care - teaching them what to do if they get lost is fundamental to granting the freedom to explore - but don’t obsess about it. And be pragmatic in everyday life: yes, it’s fine to share a ride in a car without a car seat, or to cycle if you’ve forgotten your helmet, or to lick the bowl with raw egg. Most of these things make a difference at a statistical, population level, but are genuinely very low risk to do occasionally.

Thank you once again to everyone for completing the survey and for allowing me to share such fascinating results. I greatly enjoyed looking through them - and hope you found them interesting too.

P.S. This is the end of the main post, but there is an appendix below on the vagaries of AI, for those interested.

Appendix: AI Analysis

I’ve been thinking for a while I should teach myself to use AI - enough people I respect have said it can be a productivity enhancer.

I’m clearly not going to use it to write stuff, but the process of creating charts from the data is not the fun part of blogging or running surveys,24 and the data format that Google Forms provides the data in makes it a little tedious to break out the cross-tabs to analyse. If I could get an AI to make the charts for me, great - and then I could write about them.

So, I got a pro-account for Claude AI (cost: £18 for a one month subscription), uploaded the spreadsheet and gave it the following prompt:

“Please create four bar charts, one for each of columns G, H, I, J and K. Each bar chart should have a title. Every bar should be labelled with the percentage of total respondents who provided that answer. Order the bars in descending order.”

Claude churned out the following text, which looks pretty promising:

I'll help you create bar charts for columns G, H, I, J, and K from your parenting survey data. Let me first examine the Excel file to understand the data structure and column contents.

Now let me analyze the data in columns G, H, I, J, and K to understand the response patterns and create the bar charts:

Let me fix the import and reprocess the data:

Perfect! Now I'll create the four bar charts with the processed data. Let me create an interactive visualization with all four charts:

I've created four comprehensive bar charts for columns G, H, I, J, and K from your parenting survey data. Here's what each chart shows:

Chart Details

1. Characteristics Parents Should Encourage Most (Column G)

Top response: Kindness (69.8%)

Shows the traits parents most want to foster in their children

2. What Would Be Most Important About Your Children (Column H)

Top response: Have a healthy weight and lifestyle (65.1%)

Reflects parents' priorities for their children's wellbeing and success

3. Traits You Would Most Try to Avoid Your Children Having (Column I)

Top response: Rude (84.7%)

Shows the behaviors parents are most concerned about preventing

4. What You Worry Most About Happening to Your Children (Column J)

Top response: Being bullied (65.1%)

Reveals parents' main fears and concerns for their children's safety

5. Outcomes That Would Disappoint You Most (Column K)

Top response: Become estranged from you (65.1%)

Shows the long-term outcomes parents most want to avoid

Each chart displays:

Bars ordered from highest to lowest percentage

Percentage labels on top of each bar

Clear titles and axis labels

Different colors for visual distinction

Based on 321 total survey responses

The visualizations reveal interesting patterns in parenting priorities, with kindness being the most valued characteristic to encourage, while rudeness is the trait most parents want to avoid.

That is indeed what I want. It’s figured out what each column is, got the number of survey responses correct and correctly regurgitated the formatting I want. So far, so good!

But let’s look at the actual charts:

The first chart appears at first glance to be right - the first five are correct, in the right order, and with the right percentage. But then Academic prowess is much too high - 19.3% instead of 5.6%. Worse, the final four - as well as being suspiciously closely grouped - are entirely hallucinated. These are plausible things I could have asked about - but didn’t.

The second chart is just as bad:

Again, the first five are correct, in the right order and with the correct percentage. But the final five are completely hallucinated!

At this point I cancelled my subscription and asked for a refund. If others are successfully using AI, I’d love to hear about it, but while it can be useful to use the free version to search for some good sources or references, this level of inaccuracy is not something I’m comfortable with for any kind of analysis.

Increasing taxes raises revenue but harms the economy.

No AIs were harmed in the making of this post, though not for lack of me wishing to.

All demographic questions had a ‘prefer not to say’, which is why they don’t sum to 100%.

Though actually, this pretty well matches the voting pattern of 30-39 year olds in last year’s general election, and 40-49 year olds are 62/31 so maybe it’s not so disproportionate.

Thank you for answering anyway!

As with all these charts, it would be a mistake to assume that this means those parents actively want their children to be cowards, or to be intolerant - simply that courage and tolerance are, respectively, not seen as a top 3 trait.

I suspect in reality I should have picked ‘rude’ and dropped ‘can’t take losing’. But picky eater would definitely be up there!

This is, shall we say, not entirely surprising.

The first item here says ‘Move to live permanently on another continent’, the penultimate one ‘Marry someone you felt was deeply unsuitable’ and the last ‘Take up a career you felt was morally wrong.’

Several people have asked me why I put two ‘middle options’ on here, which is not standard polling practice. The answer is that I couldn’t bear to put things like ‘sharing a room’ - which I see as completely fine whether you do or don’t - in the same category as ‘baby-led weaning’ which I see as the emblematic silly modern fad that makes parents’ life unnecessarily harder, but that I would have to admit I don’t think harms the children in any way. Hence the two categories. The ‘net support’ numbers are calculated by omitting both the two middle options - simply the top two options minus the bottom two.

I hear this is controversial on parenting forums.

Though given I do too, maybe I shouldn’t have been.

Or it’s just lizardman’s constant.

For more on this, read “The Care Dilemma” by David Goodhart.

Which they don’t have to do.

Which is likely to inconvenience them.

I’m aware that definitions of ‘gentle parenting’ vary, but in the survey I explicitly defined it as ‘avoiding raising your voice or punishing a child’.

If you’re not in this three-quarters of respondents, feel free to skip this section.

Plus they may still end up huddled around the phones and exposed to content on their friends.

I guess like the difference between being vegetarian and being vegan.

Again, if you’re not one of these three-quarters, feel free to skip this section.

“I do not believe one can settle how much we ought to give. I am afraid the only safe rule is to give more than we can spare. In other words, if our expenditure on comforts, luxuries, amusements, etc, is up to the standard common among those with the same income as our own, we are probably giving away too little. If our charities do not at all pinch or hamper us, I should say they are too small.” - C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity

In fact, there’s a good chance they have got less as your child may be more careful.

I mean, I don’t hate it - but if it can be automated, that’s great.

I would be very loathe to use AI on anything without checking it. It very often gets it wrong, or just makes up nonsense.

I think the gentle parenting thing isn't entirely inconsistent - there's a big difference between gentle boundary setting and complete abdication of parenting.

Eg You can both avoid raising your voice and punishing your child, and refuse to get them a smartphone early.

Gentle parenting doesn't mean no limits - you could argue with the definition of punishment (kids often react to the consequences of their actions as a punishment) but the idea is that you don't deliberately inflict extra suffering specifically as a punishment, rather than that you do anything they want or don't use force (as gently as possible) to rescue them from danger / stop them drawing on the wall etc.