Contra Ansell on Bloc Politics

Reminder: The Edrith Christmas Quiz is available here, with answers available from Epiphany.

There’s a lot of talk at the moment about how our politics is arranging itself into two ‘blocs’, one on the right (Conservative + Reform) and one on the left (Labour + Lib Dem + Green)1, and that argues:

Most shifts in headline voting intention are caused by voters moving within blocs (or to ‘don’t know’), with comparatively few voters moving from one bloc to the other.

Within each bloc, most voters will consider voting for the other party(ies) in that bloc much more readily than they will consider voting for parties in the other bloc.

Therefore, political parties should focus on taking voters off the other parties in their bloc, not attacking the other bloc. In particular, that Labour should focus on reclaiming votes lost to the Lib Dems and the Greens, and also that the Conservatives should focus on attacking Reform.

One of the fullest expositions of this new ‘bloc politics’ is outlined by Ben Ansell in this piece; it is also referred to here by Stephen Bush, amongst others.

I will now proceed to disagree with Ben in a specific and limited way.2

At this point, I believe, I am supposed to performatively trash Ben’s piece by saying that it is the worst article written since Baldric’s treatise, Root Vegetables I Have Known, was rejected by the East Anglian Journal of Turnip Studies. I will, however, inexplicable fail to do this, as it, and its predecessors, are actually very good pieces, filled with all kind of interesting data.

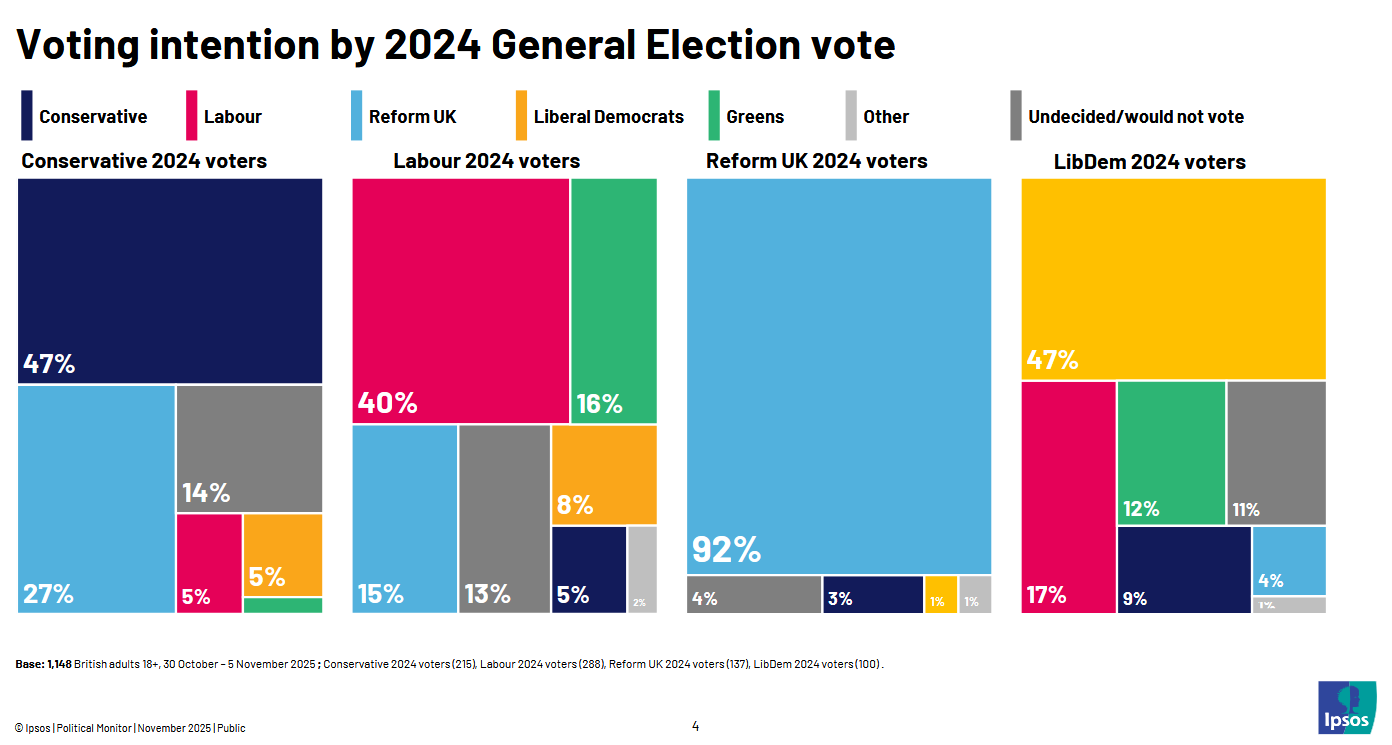

In particular, it is true as the chart below shows, that Labour has lost more votes to left-wing parties than it has to Reform, and that the reverse is true for the Conservatives. (Labour has also lost a bunch to Don’t Know).

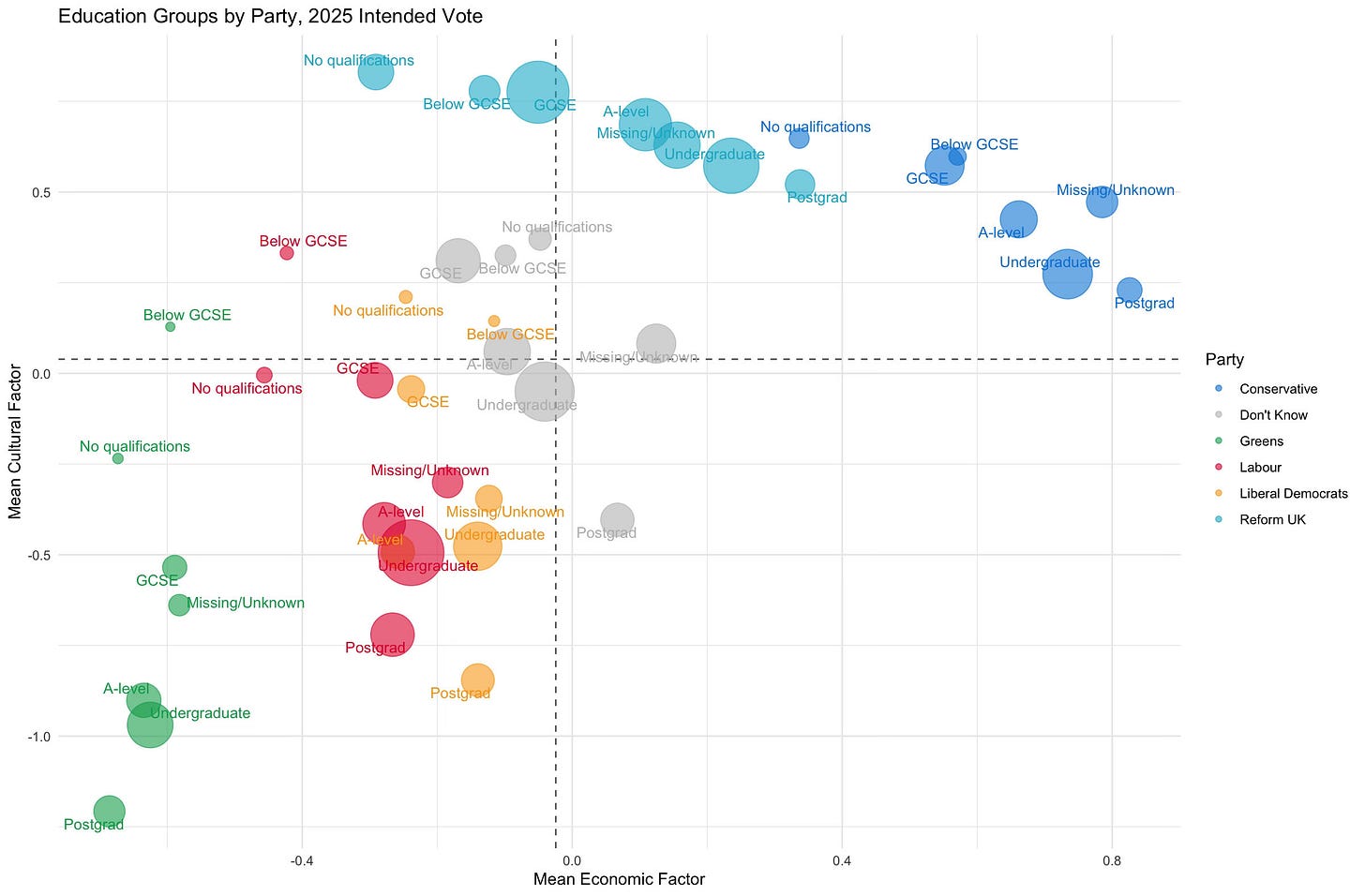

As Ben’s famous bubble plot shows, it is also true that the average voter views of the left-wing and right-wing parties do appear to fall, more or less, into two blocs, with Don’t Knows looking more like left-wing voters.

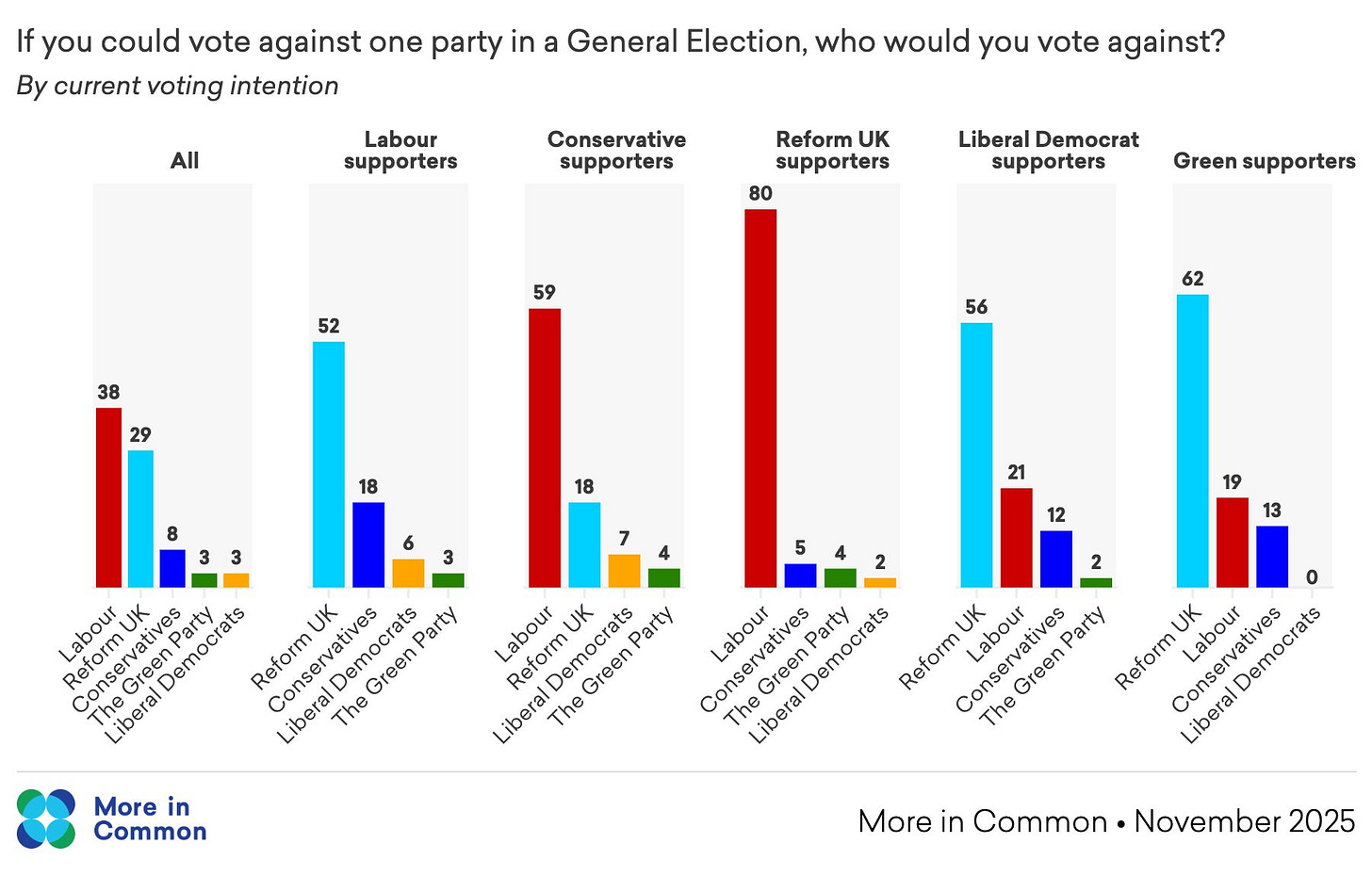

And if we look at who people would vote again, this again looks pretty like we are getting bloc behaviour.

So, where’s the disagreement?

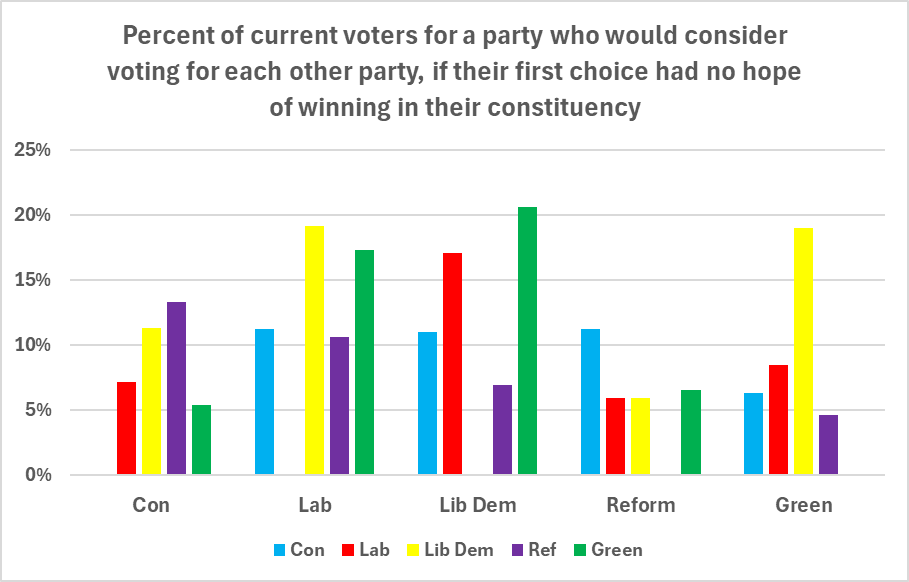

Well, bloc politics isn’t perfect. It’s hard to say for certain which other parties someone might switch to, but Opinium did a poll earlier this month where they asked which other parties people would consider voting for if they lived in a constituency where their first choice had no chance of winning.3

If we look at the results, we can certainly see people are more likely to vote for a party within the same bloc, but we also see a fair number of cross-bloc voters, particularly between the Conservatives and Lib Dems, but even some Green/Reform swingers.4

More importantly, however, is the fact that the size of the blocs are far from fixed.

Using polling averages from the UK Election Data Vault, at the last general election, just 18 months ago, the left bloc enjoyed a 14 point lead over the right bloc.5 Since then, the right bloc gained rapidly as Labour became unpopular, taking the lead and peaking at over 5 points ahead in September. This then fell as the Tories lost popularity (despite Reform cannibalising much of this support), before gradually gaining again and finishing the year at about 3 points ahead.6

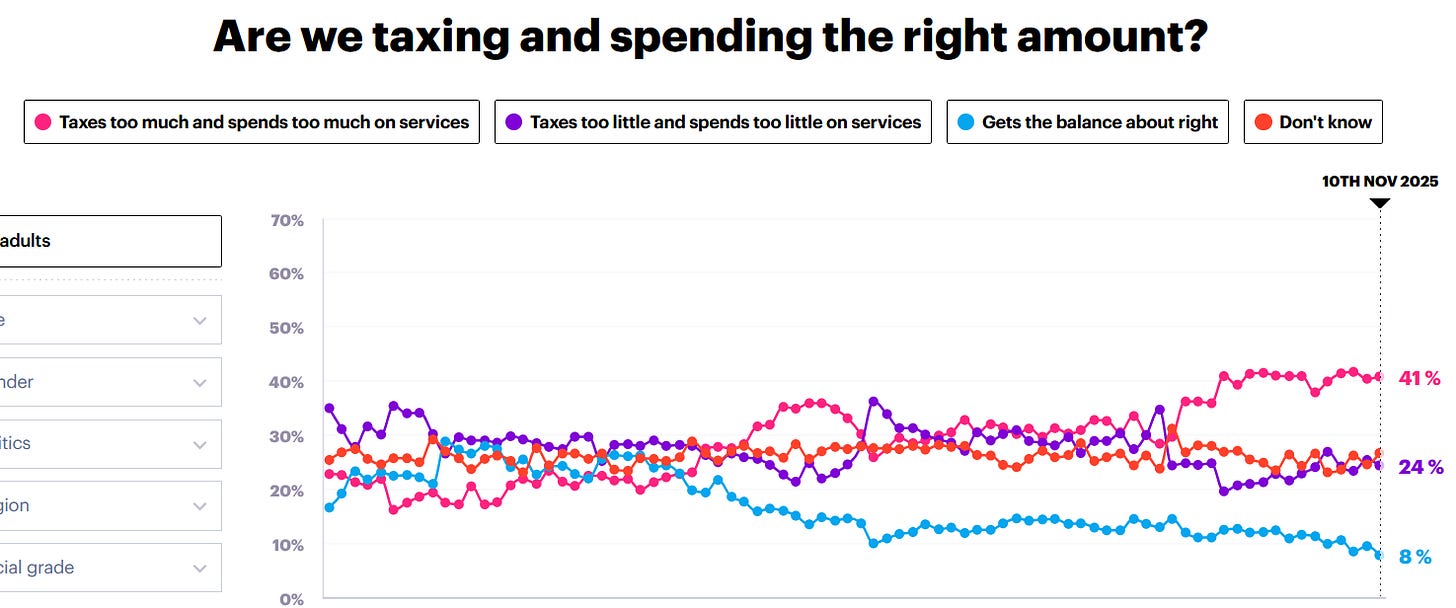

This is an 8.5 point swing from left to right since the election. Two reasons for this include anti-incumbency voters shifting from opposing the Conservatives to opposing Labour, and a broader shift away from supporting more tax and spend to supporting lower taxes, which favours the right bloc.7

It would be folly to extrapolate that over the next three years - but it does show that people do move between blocs, and to a significant extent.8 Similarly, between 2010 and 2015, the right bloc’s lead went from -12.89 to +7.5 - enough for Cameron to extend his plurality to a majority, despite UKIP taking a significant number of Conservative votes.

The difference between a right bloc on 55 and a left bloc on 40, or a left bloc on 55 and a right bloc on 40 - both of which are entirely plausible - is clearly significant.

But isn’t it still easier to move voters within a bloc, than between them?

So far we’ve failed to refute the thesis: sure, it’s possible to move people between blocs, but if intra-bloc movement is easier, shouldn’t parties still focus their efforts there?10

To answer this, we need to recognise that politicians - and journalists, activists and others engaged in politics more broadly - want a number of different things. In particular, I will be making the bold claim that most politicians actually care about changing the country in some way, as that’s why they went into politics in the first place.

I propose that those actively engaged in politics want four things:

Most importantly, they want their preferred party to win.

If their preferred party doesn’t win, they want their party to have a role in influencing the government, for example in a coalition, as a king-maker, or as part of a confidence and supply arrangement.

If neither of these occur, they want the party they like second best to win over parties that they would less like to see in government.

Regardless of which party wins, they want policies they support enacted, and policies they oppose not enacted.11

Consider a hypothetical right bloc individual whose preferences go Conservative>Reform>Labour>Lib Dem>Green.12 Or a left bloc individual whose preferences go Labour>Lib Dem>Green>Conservative>Reform. Or other examples, where the first preference is Reform, or Lib Dem, or Green, but the votes remain ordered.

And yes, this doesn’t describe everyone;13 indeed, I would wager that readers of this blog include a higher than average proportion of cross-bloc preference voters. But the evidence suggests it does describe a decent number of people. And my hunch would be that MPs, activists and ‘the parties in the media’ are likely, in general, to be more consistent ‘bloc voters’ than the general public.

For such individuals, actions which target intra-bloc voters certainly increase the probability of (1). But they do nothing to help (2). In a left-bloc victory, where, say, Labour get 300 seats, the Greens and Lib Dems have a strong chance of being part of a coalition; similarly, if either the Tories or Reform get the most seats but fall short of a majority, the other party is the natural ally. In today’s polarised politics, it is almost inconceivable to see any left bloc party taking a junior role to one of the two right bloc parties, or vice-versa.

Furthermore, targeting intra-bloc voters actively harms (3). Sure, it’s great if it pays off, but if it doesn’t, you’ve reduced the chance of victory from your own bloc - your second or third choice party - in favour of a party from the other side, that you would be much less happy to see in government. Intra-bloc feuding may actually damage the bloc as a whole, to the extent that it discredits ideas, concepts or policies that both parties believe in.

Finally, on (4), to the extent that a bloc increases in size, and its values and policies gain popularity amongst voters, this places pressure upon the other bloc to adopt some of these policies - and makes it easier for you to implement them if you win. A good example is the way in which Labour has significantly curbed legal migration. On most policies, the differences between parties within each bloc is a matter of degree, not of direction or fundamental difference, so intra-bloc feuding may damage the popularity and credibility of these ideas - whereas winning over voters to what you believe, gaining greater support for your blocs ideals, fundamentally increases the chance of getting what you believe in adopted.

In contrast to targeting voters in your own bloc, effectively14 targeting interbloc switchers and enlarging your bloc helps with all four of these objectives.

A semi-cooperative board game

Imagine a semi-cooperative board game set in the Reconquista, in which each player controls either a Christian or Muslim kingdom in the Iberian peninsular.15

Players of the same faith are nominally allied, with all Christian players gaining ongoing bonuses - income, prestige, victory points - for the amount of Iberia under Christian control, and vice-versa. But anyone can attack anyone, and it is often easier to improve one’s position by nabbing a border fort off a co-religionist than by mounting an expensive and risky expedition against the infidels.

Towards the end of the game, we can expect every player to engage in a mad scramble for victory points, often at the expense of their own side. But overall, where do you think the winning player is most likely to be found: amongst the side who, at least to some extent, focused on pushing back the frontiers of Spain/Al-Andalus, or amongst the side who spent the whole game taking lumps out of each other?

Of course, parties have to pay some attention to their position within their bloc - or they will be left beind. If Nigel Farage makes a gaffe, Kemi Badenoch should clearly exploit it. Where there are genuine differences between parties in a bloc, or when one party is much stronger, this may also be sensibly emphasised. It helps the Conservatives more than Reform when the conversation is on tax and spend, so they should aim to keep it there; similarly, Labour might find benefits in highlighting the Green’s position on defence, NATO and Trident.

Intra-bloc voters may be easier to attract - but winning over inter-bloc voters offers deeper and more substantive benefits. It is hard to pin down an exact ratio, but at this stage of the electoral cycle, it would seem reasonable to value every vote won from the opposing bloc as worth 2 or 3 of those won from the same bloc.16

When the next election approaches this long game goes out of the window, as each party must then seek to maximise its own position as rapidly as possible - which inevitably will mean playing the easier, intra-bloc game. But that in itself is much likelier to lead to victory if the preceeding years have been spent making the bloc itself is as large as possible.

Plus SNP and Plaid in some formulations.

As the saying goes.

Lord Ashcroft also did a poll last week, in which he found that “Supporters of left-wing parties overwhelmingly say another party of the left would be their second choice. But one third of Reform voters would vote for a non-Tory if Reform weren’t standing, and more than half of current Conservatives name a party other than Reform as their second preference.” The poll got results quite out of line with the polling average on headline voting intention, including Reform on 25 and Conservatives on 22, 4 points ahead of Labour on 18 - so I’m not sure how reliable it is.

Note that the questions were not mutually exclusive - a Labour voter who would consider voting Lib Dem or Green could tick both options.

I am defining the right bloc as Conservative + Reform and the left bloc as Labour + Lib Dem + Green. There are arguments for and against including SNP and Plaid in the left bloc: they are left of centre, but not as clearly as the others (particularly in Scotland there are plenty of right-wing nationalists) and, as their voters are so concentrated, they impact the overall results in very different ways.

I have left them out; however, as the national share of votes going to SNP and Plaid varies very little, including them does not alter the overall trend other than to shift the line c. 3 percentage points down at all points.

The Election Maps poll of polls similarly puts the right bloc about 2.5 points ahead, while the Politico poll of polls puts them level, but hasn’t been updated for a week.

Not always directly. Someone may move from Labour to Don’t Know, and only 2 years later move out of Don’t Know to Conservative or Reform (or Green, Lib Dem or back to Labour).

I am, sadly, including the BNP in the ‘right bloc’ in 2010 as they got a vote share of 1.9%.

There are clearly a bunch of things that parties can do which boost their standing with voters for all other parties - increasing their perceived competence, or improved communication, or not committing gaffes. But there are also choices that parties make, where improved standing with some voters will hinder them with others - choices of policy, or language, or simply which topics to raise and talk about.

Though this is obviously not uncorrelated with their preferred party winning.

Who could this be?

This word is important. It is entirely fair to criticise Labour by observing that their current strategy does not seem particularly effective at winning back Reform switchers or enlarging the left bloc. It is more of a leap to say that this isn’t something they should even be trying to do.

Guess who has recently reread The Lions of Al-Rassan.

Again, as long as one doesn’t completely lose one’s position.

Your Board Game analogy sounds very similar to the Board Game 'Britannia' where the players are given counters to represent armies invading the Island from Julius Caesar to William the Conqueror. In the last few turns, there are Saxons, Normans, Norwegian Vikings, Scots, Welsh, Picts, Dubliners, and maybe the remnants of the Romano-Brits all piling in to gain what teritory and points they can on the final Turn

Merry Christmas and may you enjoy many Parsnips and root vegetables