Whatever happened to my Physics Olympiad cohort?

And what does this say about the role of intelligence in life success?

A follow-up post to Whatever Happened to My Faststream Cohort?

Twenty-two years ago, in my final year of secondary school, I was one of 15 finalists1 in the British Physics Olympiad (BPhO). After four days at a training camp just outside Oxford, we took some more mega-hard tests - one theory, one practical - and the top five were selected to represent the UK in the International Physics Olympiad (IPhO) held that year, in - of all places - Bali2.

For those unfamiliar with the Physics Olympiad, it strongly resembles its better known cousin, the Maths Olympiad, which begins with the Maths Challenges set in schools3. One takes an initial paper in school, on which one can get a Bronze, Silver or Gold4. Those who get a high Gold are invited to take another, significantly more difficult paper, also at school. Then the top 14-15 are invited to the training camp and final test for the International Olympiad. Think of Young Musician of the Year, although significantly less watchable5.

So 22 years on, where did we all end up?

First, a bit more about us. Twelve of us were in Year 13, with three having qualified at a younger age: two in Year 12 and one in Year 116. My particular claim to fame was to be the only one of us who reached the final without taking Further Maths.

For those interested in such things, in a complete opposite of my Faststream cohort, which was balanced by sex but almost entirely white, we were fairly ethnically diverse7, but almost all boys - though it’s worth noting that the single girl was one of those from the year below and did qualify for the IPhO team.

We all went to Cambridge or Oxford8, to do a mixture of maths, physics/natural sciences9 and engineering (one person). Following this, eleven of us went on to do PhDs, while four of us (myself included) did not. And this is where we are now:

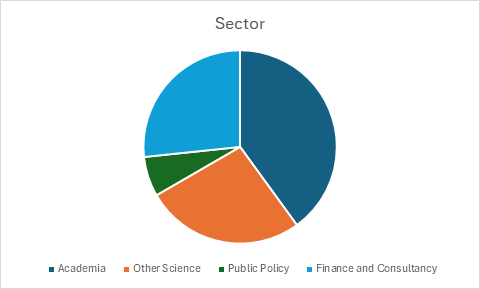

Two thirds have stayed in science - six in academia and four in industry - while four are working in finance and consultancy. One (me) has moved into public policy10.

Eleven of us still live in the UK, four of us abroad, two in the US and two in Europe11.

I wanted next to look at how senior people were, but - unlike in the Faststream post, where nearly 80% had remained in the civil service or wider public sector - found it fairly difficult to assess whether an Associate Professor is more or less senior than a Senior Research Engineer. So instead, and especially as there’s a much greater diversity of roles, I’ll just say what everyone is doing.12

In no particular order, the roles we currently hold:

Senior technical role at a public/private research institute (following 15 years in industry).

Post-doctoral researcher at a Max Planck Institute.

Portfolio manager at a major hedge-fund (after having reached a senior level at a young age at UBS).

Manager at one of the ‘Big 4’ professional services firms.

Director at a major biotech firm in Switzerland.

Associate Professor at the University of Chicago.

Senior Research Associate at the University of Oxford.

Senior Research Engineer at a major tech company.

Associate Director at one of the ‘Big 4’ professional services firms.

Associate Professor at UCL (after a period living ultra-sustainably and chairing a small environmental charity).

Director of Research at a think tank.

Head of Strategic Finance at an insurance company.

Academic at the University of Cambridge and co-founder of a start-up.

In a technical role in a STEM start-up (having previously worked in a maths-heavy role in Government for some years).

Associate Professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

There are three things I notice about this list of jobs.

They’re pretty varied. I half expected most of us to be in academia - and perhaps that’s where most of us thought we were heading at 18, too. But actually only 40% are in academia, another chunk in industry, and a third in public policy, finance and consultancy. Even within academia there’s a wide diversity of fields including genetics, decision-making and planetary science, not just physics. Clearly physics and maths really do underpin the other fields!

They’re all pretty good jobs. They look interesting and meaningful, as if the person has made an active choice to end up there. Almost all of us are probably higher rate taxpayers13 and a number are likely earning over six figures. They’re the sort of jobs that, if you’re a parent and were told your kid would end up there at 40, you’d be pretty pleased. Or, to put it another way, if a country wanted to give every BPhO finalist a visa, aiming to pursue Neil O'Brien’s ‘Grammar School of the Western World’ immigration strategy, this would be a pretty good bet.

But at the same time, none of them are really top jobs. No-one’s won a Nobel Prize. Perhaps more realistically, no-one’s a Fellow of the Royal Society, or a full professor, or a partner at the Big 4, or a Government Minister, or a director-general in the civil service, or a KC14, or on the C-suite of a FTSE250 company, or founded and sold a highly successful spinout. These are all things that people can absolutely achieve by 40.

So why is this?

We were all fairly bright. We obviously weren’t the cleverest 15 people in the country: plenty of subjects exist other than physics15. We weren’t even the best 15 people in the country at physics, because, sadly, not every school does the Physics Olympiad16 - just the best 15 the organisers could find. Aside from Olympiad considerations, in terms of wider markers of what people might consider markers of intelligence, we all went to Oxbridge to do a STEM subject and all or almost all got a First. One of us17 got the highest score in physics that year at Cambridge in Part 3 Physics (i.e. fourth and final year of the course). Most of us were just ‘normal’ clever, but three in particular were really exceptional18, each of these three having qualified for BPhO one or two years early and simultaneously qualified for other Olympiads.

So why has this translated - for all of us - into good, but not exceptional, life success?

This is a classic example of how ‘The tails come apart’, a concept written about by a guy called Thrasymachus19 (all diagrams are from his article) but that I first encountered on Scott Alexander’s blog.20

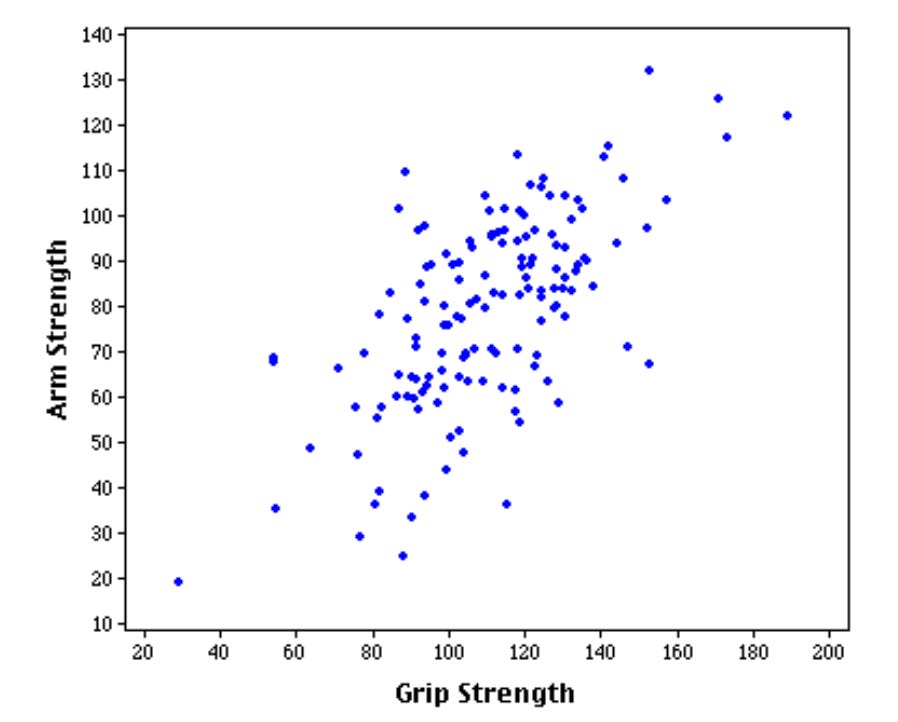

Essentially, when you get two quantities that are highly correlated - height and basketball ability; reading and writing scores in the US SAT; chess ability and maths ability - then, even if there’s a very good correlation overall, the best person at one is unlikely to be the best at the other.

Here’s an example below showing grip strength and arm strength, two highly correlated functions of what we might casually call ‘strength’. Now, if you pick out a big beefy guy, bulging with muscles, and compare him to a 5’ 7” thin weedy guy, then you can predict pretty well that the first person is going to be ‘stronger’, and have better arm and grip strength. But you can also find plenty of people where one has stronger grip and the other stronger arms. And, crucially for this purpose, it’s very unlikely that the person with the strongest grip strength is also going to be the person with the strongest arm strength.

That’s what we see here. Intelligence21 is definitely a help in life success. We see this in all kinds of careers from politics to finance to science and even in things which seem very unconnected, such as sport.22 It can open doors, give you choices and make life easier whatever career you're in - as can be seen, all of us have done pretty well. It's definitely something you'd rather have than not.

But at the same time, in real life, lots of other things are also important. People skills, from management ability to networking. Creativity. Ambition, drive and resilience. Risk-taking appetite. Sometimes just the willingness to put in 70 hour weeks year after year, or to uproot your life and move across the country for that next step up..

For the mpst senior jobs, it seems likely that these other factors are even more important. You want the CEO to be smart, but they're not usually literally the cleverest person in the company. Other factors predominate at that level. So while it's a safe bet that your BPhO finalists in any year will be successful, you might need to look a little wider for those who'll reach the very top.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like Whatever Happened to my Faststream Cohort? - and don't forget to share and subscribe, if you're not already signed up.

Technically, 16 of us were invited to attend this but one person couldn’t make it. When looking up the 16 of us, I was unable to find any information beyond 2008 about one individual. These two factors cancel each other out and I’ll refer to ‘15’ throughout the rest of this piece.

I was first reserve, which in the words of the second reserve, meant that I ‘had approximately zero chance of going, and he had approximately zero squared’. To make me feel better about just missing out, I actually came 7th, not 6th - but one of the top five had also qualified for another Olympiad which clashed with IPhO, and chose to do that one instead.

In Maths, at national level there are junior, intermediate and senior version of the Maths Challenge, that can be taken at various points throughout secondary school.

Or nothing.

Though the practical exam in the final would probably make entertaining television, given how badly some of us did at it (our final answers for - if I remember correctly - the temperature of a lightbulb filament ranged across several orders of magnitude).

I think. There were definitely three who were not in Year 13.

Over 25% ethnic minority, well above the national average for that cohort in 2002.

More to Cambridge

At Cambridge you can’t do just physics, though you can specialise in it from, effectively, the second year onwards.

Which I did immediately after graduating; hence the post on the Faststream.

Only one in the EU.

And, where it’s notably different, what they did before.

Not that this means what it used to.

OK, that one was probably never going to be that likely.

I hear stamp collecting is very popular.

At this point we must break for my regular rant about how the Department for Education has a strong aversion to anything that might support or stretch high ability pupils - Olympiads being one example. Each year they spend c. £3m to support the World Skills tournament (in carpentry, electricianing, etc.), but can rarely deign to even send out a tweet congratulating the UK IPhO/IMhO/etc team on their results. I don’t begrudge the skills guys their money - we absolutely should be doing more to support vocational skills - and nor do I think BPhO needs a fraction of this money. But would it kill them to write to every secondary school / 6th form college, making them aware of the Olympiads, and being clear that this is the sort of thing they expect schools to be entering their high ability pupils in?

Not me!

Again not me!

A pseudonym, I presume, or else his parents were really into Ancient Greece.

Where else?

And, obviously, a good education to bring it out. But even without that it’s often a help.

I know it might not always seem it, but the average intelligence of US senators - whether measured by SAT scores, IQ, or anything else you like - is noticeably higher than that of the average population.

Very interesting post, thank you. The slight comment I would add (in the context of professional academia and research) is also the role of luck (or right area, right time). I think no-one (with the possible exception of some areas of pure mathematics) gets to be an FRS before the age of 40 without the stars aligning in some way.

Also, in terms of research discoveries and the fact we don't know what nature will give us. One example is the Large Hadron Collider. We know now that the only new particle accessible to the LHC when it turned on was the Higgs boson of the Standard Model, but it was perfectly plausible that other stuff could also have been found (with consequent effects on careers).

I'm a year younger than you, I believe, and did the IMC maths camp in 2000, age 14 - which had about 25 us from that plus the Maths Olympiad team. I've only kept in contact with one person, and can't recall others' names, so it's interesting to see what your physics set went on to do.

'Good, but not exceptional, life success' is accurate for me too.

What's perhaps mildly interesting is that I didn't build a career in STEM at all, but rather studied social anthropology, wrote a book about environmental history & politics, and now work on the business side of journalism. Most people would say that qualitative and quantitative intelligences are quite separate abilities - but I managed to get the best final-year exam results in the LSE for much the same reasons I did well on the IMC maths exams: work ethic, study skills, very good prior education, structural privilege. (Actually, I didn't much work at the maths? Anyway.)

I find it curious that, on the one hand, there was that much skill transfer between subject domains. And yet I couldn't transfer it across to, say, getting shockingly good at office politics, strategic career planning, or general hustle.

My hunch is that just about everyone at maths or physics camp is heavily intrinsically motivated (by challenge, curiosity, autonomy etc) - whereas professional hyperachievers tend to have significant extrinsic drives (money, competition, recognition)? So your mathmos will do interesting things, and probably do them successfully - but there is by and large an ambition deficit.

Curious as to your take.

What drives Fields and Nobel medallists, I'm not sure :) Perhaps they're just intrinsically motivated deep workers who get very lucky? Or perhaps the recognition drive starts creeping back in, and they get strategic about what they work on and how.