Whatever Happened to my Faststream Cohort?

Seventeen years ago I joined the Civil Service Fast Stream, in what was then the Department of Trade and Industry1(1). I was part of a cohort of 15 of us in the DTI, or about 300 across the whole civil service, all of us excited to join a programme that offered the opportunity to rise to senior levels within the civil service.

So how did that work out for us? With today's internet resources, I looked up the 15 of us in my cohort, and the 15 in the year above (with whom we were partnered in a development programme) to see what had become of us, in terms of where we were now working and how senior we had managed to become. The anonymised results are set out below.

The Fast Stream, when I joined, marketed itself as a graduate programme that offered a unique opportunity to set yourself on a path to join the Senior Civil Service, and, potentially, the most senior positions within it. I can't remember the exact wording it said then, but today it says:

"Fast streamers work across the Civil Service, typically gaining experience of working in different government departments, as they are developed to become our future leaders and managers. The programme offers unlimited career potential to reach the very highest levels of the organisation."

https://www.faststream.gov.uk/about-us/index.html

The cohort I was part of had people a range of ages on it. At 22, I was the second youngest, with most people being between 23 and 26. There was one individual who was 30, but that was unusual. So, 17 years on we're all about half-way through our careers, some a little less, others a little more.

For those interested in such matters, of the 30 of us in our year and the year above, we were exactly 50:50 split between male and female, and almost (though not quite) exclusively white2.

DTI was considered a middle-ranking department in terms of prestige; not one that stood out, such as FCO or Treasury, but nor one that was seen as less prestigious, and was also a heavily policy-focused department. I should add that this post only looks at those of us on the Generalist Fast Stream (including the Science and Technology sub-stream of that), not the Economist or other specialisms. Nowadays, there are many more specialist streams, and the structure of the Fast Stream has also changed, so this should not be treated as an indelible guide to what happens now - simply a snapshot at a moment in time.

I'm only still in touch with about half a dozen of us, but of the 30 of us in my cohort and the cohort above, I managed to track down 28 of us using LinkedIn and Google. The analysis below is based on this; if anyone has got promoted recently and failed to update their LinkedIn, on their head be it!

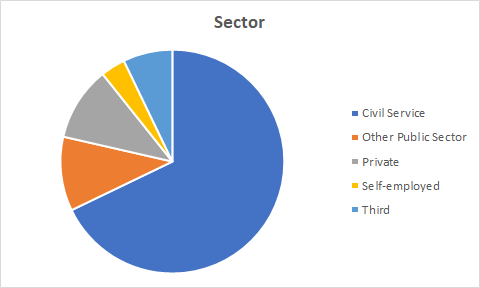

The first thing I was curious about was how many people had stayed in the Civil Service:

Surprisingly to me, about 2/3 of people had, though in a wide range of departments. This is a pretty impressive retention rate and speaks highly of the Civil Service - especially given we're talking here of a highly selected cohort, who would all have had other options. Only 10% have gone into the private sector and the same number into the wider public sector, as well as two into the third sector (both policy related: one into an industry body and another in a think-tank).

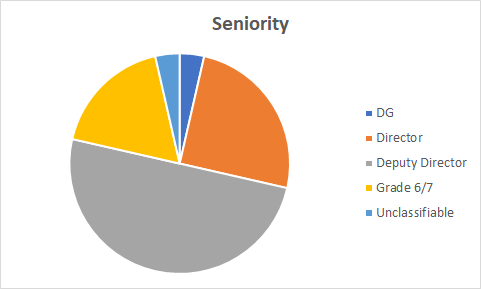

Seniority

What about seniority? It should be noted that when it comes to people working outside the civil service, I have had to make my best estimate of an equivalent seniority from the description of the role in LinkedIn3; it is, clearly, impossible to make perfect comparisons, but I do not think I am wildly wrong.

Both the median and modal result was Deputy Director, the first rung of the Senior Civil Service. Of course, it is possible, indeed likely, that many of these people could be promoted further over the next twenty years. One person has already made it to Director-General - pretty impressive for under twenty years, and they are no doubt in the pool of potential future Permanent Secretaries. Just over another 20% are at Director level or equivalent. Meanwhile 1 in 6 are at Grade 6 or 74.

Interestingly, those who've left the civil service are, on average, more senior than those who have remained. For example, five of the seven Director-equivalent roles are outside the civil service (though two of these are in the wider public sector, meaning four in total are civil service or public sector). This suggests that either (a) I'm overestimating the seniority of private sector roles5; or (b) that people who were willing to look at good options outside the civil service have been able to progress slightly quicker. This surprised me a little, because in my head I assumed that maybe people who felt their career was stalling would be more likely to move out and seek other options, but with hindsight the idea that people open to doing a wider variety of things would be able to move up faster also makes lots of sense.

Finally, the year above, on average, have done much better! They have the DG and the clear majority of the Directors - and I don't think the one year of seniority is making all that much difference. So, if any of you are reading this, hats off to you: you rule and we drool.

So what does this mean?

Overall, I think this speaks fairly highly of the Fast Stream, and the civil service more broadly. No graduate programme can select perfectly, and to have three quarters of starters reaching the Senior Civil Service within 17-18 years speaks very highly of a scheme that offers real opportunities to rise - particularly with more than 1 in 5 reaching higher grades, and one significantly higher.

The fact that two-thirds have chosen to stay in the civil service6 also speaks highly of the job satisfaction, engagement and other benefits that the career path offers - even in these days, when neither the senior salaries nor the pensions are what they were in 2006 - while also fitting people to seek senior roles elsewhere.

Despite being one of those that ultimately has chosen to leave, I know I greatly enjoyed and benefitted from my civil service career, finding it not just enjoyable and fulfilling, but something that imparted a wide-range of widely relevant skills. This analysis, snapshot as it is, suggests I'm not alone in that.

So if you know anyone thinking of the Fast Stream today - tell them to go for it!

This is the first in a series of slightly more personal posts, to mark turning forty. They will appear every couple of months over the next year, in between the more standard posts.

Subsequently BERR + DIUS, BIS, BEIS and now DBT. Though the bit of it where I began would now be in DSIT.

I remember the contrast with engineering companies I'd applied to, which were both far more male-dominated but also far more ethnically diverse.

The 'unclassifiable' person is the one who is self-employed.

It's worth noting that at least one or two of those appear to have chosen to put other things than their career first at some point (for example, following a spouse to a different country).

I don't think this is the case though, because (a) I'm pretty confident about the two in the wider public sector; (b) I can see what level these people had reached in the civil service first and it is consistent with this; and (c) a couple of these private sector roles look seriously impressive.

I don't think this is the case though, because (a) I'm pretty confident about the two in the wider public sector; (b) I can see what level these people had reached in the civil service first and it is consistent with this; and (c) a couple of these private sector roles look seriously impressive.