Rage, rage against the growing of the debt

It's past time to abolish real interest rates for Plan 2 Student Loans

Over 5 million people who began university between 2012 and 2023 have a Plan 2 Student Loan.1 Borrowing to cover fees of £9,000 or £9,250 a year, plus maintenance, they will have typically graduated with close to £50,000 of student debt - although some, such as medical students, will owe much more.2

9% of everything they earn over £28,470 a year is deducted from their income to pay down that debt3 - and any that remains thirty years after the April in which they were first due to repay is written off.

It is the interest rates, however, which are the most invidious element of the Plan 2 loan. During study, the loans accrued interest not at inflation, but at RPI + 3% - and, after study, the interest rate is pegged to the graduate’s earning, on a sliding scale from RPI (if earning £28,470 or below) to RPI + 3% (for those earning £51,245 or more).4 Between August 2023 and August 2024, all Plan 2 graduates were accruing interest at at least 7%, regardless of income.

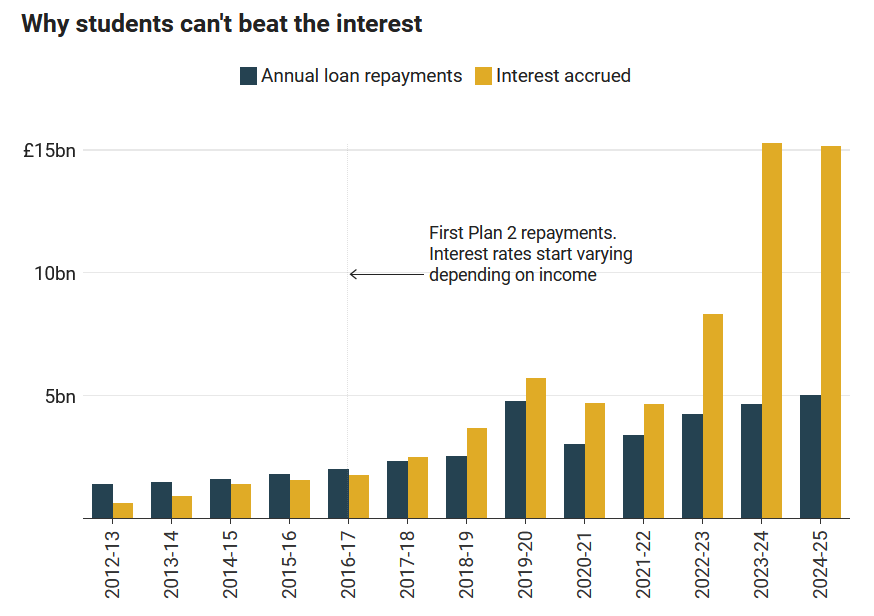

As a result, the total volume of money owed by Plan 2 students is increasing year-on-year - even though no new loans are being taken out.

At an individual level, the interest rate is brutal - with the IfS calculating the typical Plan 2 Graduate needs to earn £66,000 a year just to keep pace with the interest.5 The Times recently reported on a graduate who borrowed £49,000 but now owes £67,000 and rising - a debt that is likely to hang over her for the next 20 years.

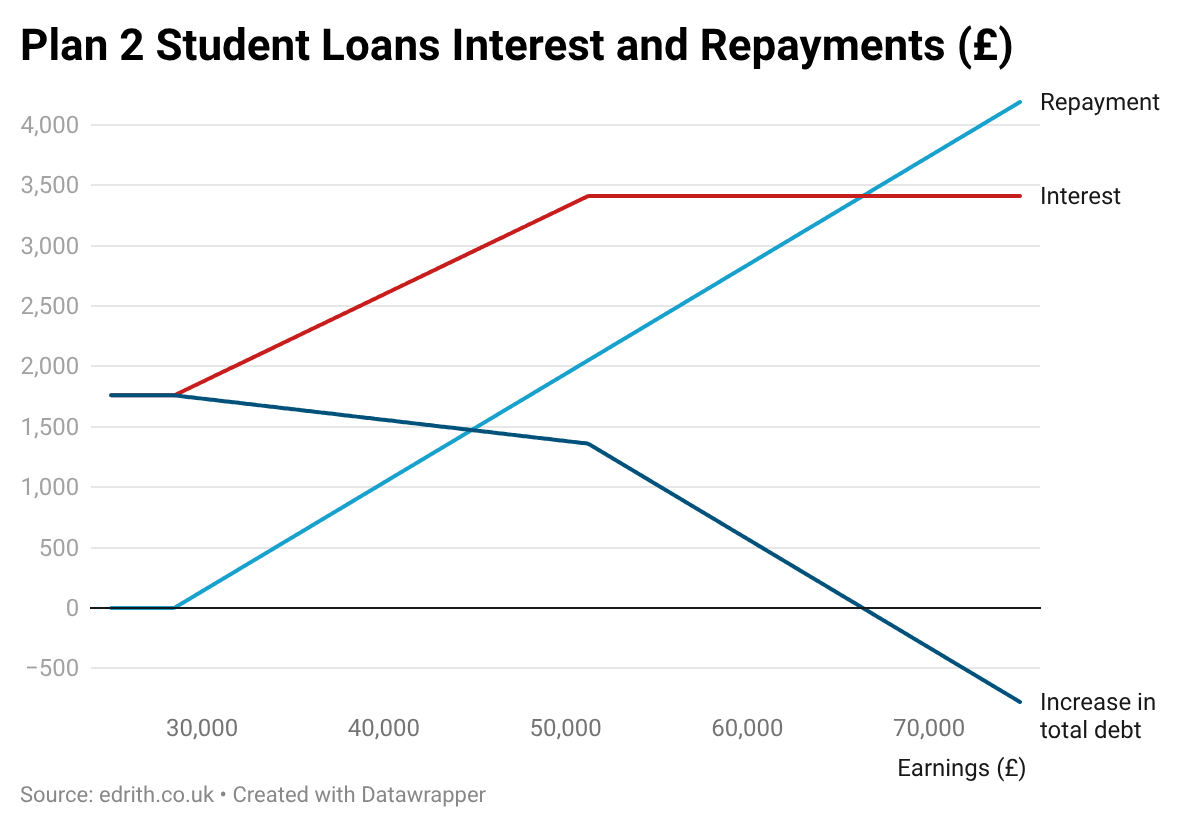

The variable interest gives the scheme a Sisyphean character. For a graduate with a typical Plan 2 loan, between the lower and upper interest rate threshold, for every additional £100 a graduate earns they repay an extra £9 - but their debt also accrues an additional £7.20 in interest, thanks to the rising interest rate.

Astonishingly, a Plan 2 graduate with £69,000 or more of debt actually sees their debt increase faster as earnings and repayments increase, because the interest effect outweighs the repayment effect.

Now, it was always understood that some people would not pay off their loan - but it was originally optimistically calculated that more than 80% would, whereas the current predictions are that it will be more like 1 in 4. The write-off provisions were understood and sold as a safety net, for those who fell on hard times, or chose low paid provisions in charities, the church or social work.

Borrowers were not led to expect that those on good salaries, earning £50,000 or £60,000 a year would still be stuck in the debt trap, their repayments failing to even keep pace with inflation. Many will end up paying far more, after accounting for inflation, than they borrowed. A recent calculation suggested that a Plan 2 graduate who moved into a good graduate job paying £36,000, moved up to £50,000 within five years and whose earnings then followed a typical trajectory, would end up paying £87,000 in real terms.

The swingeing interest rates are sometimes justified as ‘progressive’. But as progressiveness goes, it’s weak sauce. Those with parents rich enough to pay the fees up front don’t pay. High earners who didn’t go to university don’t pay. And even for those with debt, those who rapidly move on to high salaries - such as investment bankers - pay far less (in both absolute terms and as a proportion of income) than middle earners who spend the first half of their career trying to keep up with the interest, and only pay down the debt in their 30s and 40s.

The 11 years’ worth of unfortunate individuals who took out Plan 2 loans are the only cohorts who face this punishment beating. Those who went before 2012, and after 2023, have their interest pegged to inflation, so that no-one ever pays back, in real terms, more than they borrow.6 If there must be fees and loans, this is the only fair way to do it.

There’s a case that given that most graduates benefit financially from their degrees that they should make a contribution towards them.7 There’s much less of a case that they should be charged the full cost, as has been the case for most students since 2012. And there’s no case at all that they should be trapped into a stealth redistributive pseudo-tax, with punitive interest rates that see them paying back far, far more than they ever borrowed.

The great mis-selling scandal of our age

The increase of fees to £9,000 in 2012 was explicitly justified - as were previous fee increases - as necessary to fund university expansion and to shift the cost of university from general taxation to those who stood to directly benefit from it. The removal of number caps two years later was only possible because the Government would no longer be footing the bill.

By shifting to a high-fee, debt-fuelled model, with the costs kept off-balance sheet, the architects of the system - and the universities that supported it - avoided a discussion over how many people should be going to university. They knew the taxpayer would never stand for the tax rises required to send the numbers they wanted to send, if it was debated openly and honestly.

By outsourcing the decision to 18 year olds paying on the never-never, pushed by heavy pressure from schools and Government, bombarded by university advertising and pulled by their own understandable aspiration, they achieved the end they desired. And over a decade later, with those 18 year olds now in a debt trap that looks very much like a tax, paying 9% higher effective marginal tax rates. We’ve moved to a high-tax, mass HE society by stealth.

Telling an 18 year old who has failed their A-Levels, who has shown no sign of academic temperament or achievement, that yes, they to can go to university, and don’t worry about the 50 grand of debt, is not ‘kind’ or ‘progressive’ - any more than it is to give them a platinum credit card and telling them to go wild in Westgate.

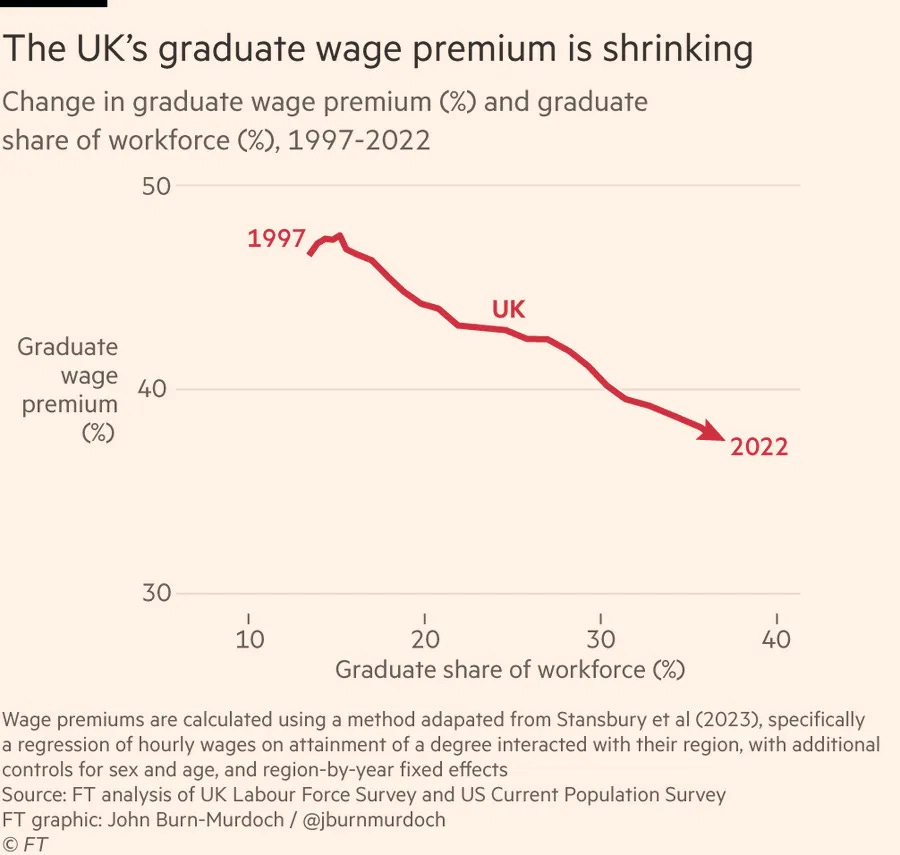

Because the ugly truth is that most of the university expansion over the last two decades has been entirely worthless - even economically harmful.8

As I’ve written before, estimates by varying methodologies find that a third of graduates are not in graduate jobs - and this is despite the ‘upgrading’ of many jobs that never used to require a degree.

The IfS has estimated that at least 20% of those who go to university are no better off, or even worse off, over their lifetime than if they had never gone - and if we consider the amount spend by the state as well, those for whom it was not worth it rises to 30%. This figure will be propped up by ‘signalling’ effects, the phenomemon whereby some employers will prefer to employ graduates, even if the degree did not give them any useful skills, simply because the degree is a signal of something they find useful.9

But the reality is that this is almost certainly a massive underestimate. The study was carried out on the cohort that began university in the mid 2000s - but the graduate wage premium has plummeted since then. Only 59% of graduates are in full time employment 15 months after graduation and the latest DfE figures show that five years after graduation, the median real time earnings for a graduate from a first degree has dropped to just £25,400 - effectively identical to minimum wage.

And as higher education has inexorably expanded, the pressure on the limited government funding we still put into the system has led to the repeated cutting of other good things - from the adult further education budget to bursaries for students from poorer backgrounds.

You are not angry enough.10

Since 2012, the combination of high fees and university expansion has led to a million or more young people being lured into degrees they did not need and were not equipped to benefit from - and charged them tens of thousands of pounds for the privilege. For millions more on Plan 2, the hidden cost of the system has plunged them into a lifetime of debt that - other than for the highest earners - they can never hope to repay.

We have created a tax on aspiration, hitting young people with effective marginal tax rates we used to only levy on millionaires: 37% for those on £30k, 51% for higher rate taxpayers, and rates in the 70-80% for graduate parents caught by withdrawal of child benefit. The impact is felt precisely at the time these people, who have done exactly what society and the state told them was the right, responsible thing to, would be hoping to buy a home, settle down or start a family.

It is the great mis-selling scandal of our time.

The best that can be said in its defence is that those who implemented it genuinely believed they were doing the right thing - but then, the same can be said about those who took us into Iraq.

The Politics of Abolishing Real Interest Rates

Some say altering Plan 2 would be tinkering, and that our higher education system needs broader reform. I agree: I would have much lower fees, fewer people going and a restoration of high academic standards. You may have your own, different, views on how things should change. But we should not allow our grand plans for tomorrow forestall us from righting the injustices of today.

There’s a total of £200 billion of unpaid Plan 2 Student Loans. Full debt forgiveness would be unaffordable - not to mention unfair to those who have already repaid (or overpaid) in good faith. But what can and should be done is to stop it getting worse - by abolishing real interest rates and making future interest the same as inflation.11

This would mean no-one on a Plan 2 loan would see their debt get any bigger in real terms. It would place them on a similar footing to those who went to university before or afterwards, and would dramatically decrease the number of graduates who see their debt pile get bigger each year, despite repaying thousands of pounds.

As to the politics, one might think that raising the repayment threshold would have more impact, as that affects how much money people take home each month. But Theresa May tried that in 2017, raising the threshold by a whopping £4,000 - and almost no-one noticed or cared. But in reality, high interest rates repeatedly come up in polling, focus groups and the national conversation as the most hated part of the system. People have a strong sense of unfairness - there is something visceral about seeing your debt go up when you are repaying thousands that people understandably detest.

Both the Conservatives and Reform are now rightly sceptical of university expansion. The Conservatives have pledged to cut university places by 100,000 a year and fund apprenticeships for young people instead, while Reform’s manifesto said they would, ‘Restrict undergraduate numbers well below current levels.’12

These are the right policies - but, taken in isolation, can give the appearance that they dislike aspiration, and young people in general. They need a positive offer as well, which this would provide.

For the Conservatives, it would be a tangible break with the past, demonstrating they recognise mistakes were made - and that they now are determined to put them right.13 For Reform, it would be another signal of how they are not the Tories.

For the Lib Dems, abolishing real interest rates would be a partial atonement for the original sin of breaking their tuition fees pledge, and collaborating in bringing in the vile system in the first place.

The Greens regularly inveigh against debt-funded education, so this should be easy for them, though they might well want to go further.

As for Labour, while their manifesto was silent in the matter, in Opposition they said a lot on tuition fees, from Starmer’s original pledge to abolish fees, to current Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson writing in the Times, ‘Graduates, you will pay less under a Labour Government’. With them now leaching votes to the Lib Dems, Greens and Reform, this would be an opportunity to make good on at least part of that promise.

Is it enough? Any policy is only part of a broader platform.

But for any party, there is value to saying, ‘You were wronged, we hear you, what was done to you was a gross injustice - and we are going to put it right.’

There are five million graduates out there - and their parents, and grandparents - waiting to hear that message.

Some reports are saying 5.7 million; however, my understanding is this is the total number of eligible students who started - and only around 90% take out a student loan.

This should be irrelevant, but for the sake of transparency, I do not have a Plan 2 Student Loan. I was fortunate enough to go to university in the £1,000 tuition fee era - though we did not think it fortunate then! - and paid off my maintenance loan some time ago. I do not therefore stand to benefit from any of the changes I advocate for here.

Technically, student loan repayments are calculated based on monthly, not yearly, income.

And let’s not even get into the fact that RPI is a bad measure of inflation, rightly abandoned by government for most other purposes, such as pensions and benefit increases.

This makes the typical loan debt per person around £55,000.

One of my proudest achievements in Government was helping to get through the Plan 5 reforms - which abolished real interest rates. At first we thought we might only be able to abolish the high interest rates for students studying - by we ended up being able to get the whole thing. Students still graduate with a lot more debt than I’d like, but at least the brutal interest rates are gone.

As I’ve written before, I’m a Bennite on this one: we should tax people because they are rich, not because they are educated. We don’t use this logic for healthcare, or schools, or any other major public service - and those who go on to earn more will pay more anyway, because we have a progressive income tax system. Still, ideals aside I wouldn’t find a modest contribution of £1k - £3k a year outrageous.

Particularly when one takes into account (a) the opportunity cost of taking students out of the workforce for three years; (b) the opportunity cost of the human capital employed in bottom-tier universities, objectively capable people doing the intellectual equivalent of digging ditches and filling them in again; (c) the drag of debt on graduates - effectively equivalent to a higher tax rate - and its impact on consumer spending and saving; (d) the impact on the government deficit and therefore borrowing.

Such as showing they can stick at something for three years.

For the avoidance of doubt, I mean angry in the sense of ‘mobilise and take political action’, not in the sense of ‘burn down the universities’.

Some ask why taxpayers should be on the hook for this. But there is a strong precedent of general taxation being used to rectify gross injustices by the State - think of the Horizon Post Office compensation scheme.

The Plan 2 scheme is immoral. Plan 2 recipients should never have been charged these usurious interest rates, and should not be charged them now. As Disney might put it, the policy ‘was wrong then and it is wrong now’. By moving to inflationary interest, graduates will still pay back what they borrowed - they will just not be gouged for more - and if the taxpayer has to pick up the tab, so be it.

As to the actual cost, it is impossible to say without modelling - particularly as much of the interest would have been written off anyway, and this largely impacts payments received by government towards the end of the term of the loans. We can say that (a) it would not materially impact the deficit, or borrowing required, over the next 5-10 years and (b) that it would cause a one-off increase to official measures of debt, due to a devaluing of the loan debt. In terms of actual cash flow, my very hand-wavy and unscientific estimate is that it might reduce revenues from loan repayments by about £1-2 billion a year each year in the 2040s and 2050s.

As with everything in the 2024 manifesto, it is unclear whether this is still Reform party policy, but I have not seen anything that would point in a different direction.

They might draw comparisons with immigration or wokery.

Here's an idea.

Make the university liable for student debt not repaid because the Mickey Mouse degree they supplied did not enable its holder to increase their earnings sufficiently.

Or just close down the useless ones. There will probably be some agreement on which the 50% worst performing institutions are.

The second graph doesn't seem to match the text around it. You appear to have a graph for someone with a debt that always accrues slower as their income rises, when your text describes someone with such a high debt that their debt goes faster for a period.