Fair and/or Progressive?

A canter through inheritance tax, student loans and the 2012 Olympics to look at what's fair - and when fairness and progressiveness come into conflict.

There's a classic logic puzzle involving how to fairly pay for water. It goes like this:

Three men were travelling on a train through a desert. One of them, foolishly, had forgotten to bring any water; fortunately, the other two more prepared travellers offered to share theirs with him. One had brought three bottles of water, the other had brought five and all three shared the water equally.

At the end of the journey, the first man brought out eight gold coins and gave them to his two companions saying, 'Here, share these fairly between you.' How should the two men most fairly share the coins?

We'll answer that in a moment, so if you want to try and work it out for yourself, don't scroll down. We'll then go on to look at other aspects of fairness and, in particular, where what is 'progressive' clashes with most people's ideas of fairness, including considering some specific examples such as student loans and inheritance tax.

But before we do so, if you're a regular reader here, why not sign up to receive an update every time I blog by entering your email address into the subscription form below? You can also help by sharing what I write (I rely on word of mouth for my audience).

Given this is a logic puzzle, I'm sure you won't be surprised to know that the 'correct' answer is not to split them 5:3, as one would imagine. It is, in fact, to split them 7:1 - 7 to the person who contributed five bottles and 1 to the person who contributed three.

To understand this, let's imagine that one can get three glasses from each bottle. There are therefore 24 glasses in all, of which 15 came from Person A and 9 from Person B. Each person drinks 8 glasses of water. Therefore Person A drinks 8 glasses himself, giving 7 to Person C (the person who had brought no water) while Person B similarly drinks 8 glasses, leaving only 1 of his 9 to go to Person C. So, as Person A contributed 7 glasses and Person B only 1 glass, the 'fairest' ratio in which to split the coins is 7:1.

If the person with five bottles were to suggest this, I am very confident that in most cases he would receive an angry rebuttal - and a demand from his companion that they split the coins 5:3, in proportion to the total number of bottles each had contributed. Though it's a fun puzzle, it's a better illustration of the fact that perceived fairness doesn't always follow strict mathematic rules - and that, in truth, fairness is in the eye of the beholder.

The 2012 Olympics

The organisers of the 2012 Olympics had a difficult task: how to distribute tickets fairly. For most sporting or musical events, we're content to allow them to be sold on the basis of price - or, in some cases, a combination of price and whoever can click 'refresh' on the site fast enough after it opens. Our sole concession to fairness is to ban ticket resales, seeing it as unfair that some traders should profiteer on the back of 'honest fans'.

For the Olympics, the organisers rightly realised that this wouldn't be satisfactory. The Olympics were, for many people in Britain, a once in a lifetime event, with literally millions wishing to attend. Some events were vastly more popular than others. Furthermore, the organisers were under a steep obligation to raise money, so some form of price differentiation was essential, ruling out a straightforward lottery, in the way that places at, for example, the Coronation Concert are distributed.

They came up with a clever system that combined straight purchasing and a lottery. The most popular events (the 100m final or Opening Ceremony) cost as much as £1000, but there were far more tickets to less popular events that were much more affordable, some as low as £20. People could apply for as many tickets as they wished, but if more people applied for an event than there were tickets then the successful buyers would be chosen by chance. There was a 'second round' to mop up tickets that had gone unsold in the first round.

It was slightly complex, but it worked. The ticketing was widely perceived as fair (based on the majority of the media coverage at the time). Of course, it couldn't avoid the fact that those near London had an advantage (not having to pay travel costs), nor the fact that people who were fans of niche sports were able to get to see these more easily - and, of course, only the rich were in the running for the most sought out events. But most people who wished to go got to go see SOMETHING - and a lucky few got to see something special, with millions becoming part of Britain's Olympic moment(1).

Fair vs Progressive

While fairness is subjective, whether or not something is progressive - in the economic sense(3) - means that the poor benefit more than the rich; or, to be more precise, the poorer you are, the more you benefit.

A benefit that is given to poor people but not rich ones is progressive. A tax is progressive if the rich pay more than the poor. Income tax, where everyone pays a fixed percentage of their income (rather than everyone paying the same amount) is perhaps the quintessential example of a progressive tax. In fact, in many countries, including Britain, we make income tax even more progressive by having higher rates of tax for higher earners, meaning they pay not just more money but a higher proportion of their money.

The opposite of progressive is regressive; i.e. that the poor pay more than the rich. Housing is a good example of something that is often regressive: someone who can afford to get on the housing ladder and pay down their mortgage may end up paying very little for housing, whereas someone stuck renting may end up pay significantly more, for a house or flat of the same size, over the course of their life.

In most cases people agree that what is progressive is also what is fair. There is an intuitive sense in which we can all see that taking £1,000 from someone on minimum wage is a much bigger deal than taking £1,000 from a millionaire. The fancy term for this is that the marginal utility of money diminishes with increasing wealth. If you earn £1,000 a month, an extra £100 a month is a big deal; if you earn £10,000 a month, an extra £100 a month matters a lot less. A paper published a couple of years ago suggests that it is roughly a log scale; i.e. to go up one 'happiness unit' you need to double your income, wherever you are on the scale(3).

Whether or not it's quite as neat as that in reality, the basic concepts hold. The richer you are, the more you can afford to pay - and the less support you need from government. It's why poll taxes have so often led to riots.

Now, that doesn't mean you can just make everything as progressive as possible. At some point people's sense of fairness kicks in: even if they're not personally paying a tax, they don't think people should pay, say, a marginal tax rate of 99%. That puts a limit on the top rate of taxation, which in the last three decades or so in the UK has been about 50%(5). We also want some benefits to be available on a universal basis, either for practical reasons, for community cohesion - or simply a sense of fairness. I don't think many people would like a world where people had to have their income checked and some pay to use a child's playground; similarly, the concept that the NHS should be free at the point of use to everyone is of totemic importance to many.

This occasionally results in some people complaining that libraries, or some other public amenity, are regressive because the middle class use them more than the poor. While technically true, there are some pretty basic arguments against this not being actually a problem:

From a community cohesion point of view, we have some services we want to be free to everyone.

From a pragmatic perspective, services that are only for the poor tend to become underfunded and poor quality. Having libraries available for everyone ensures broad based support and better funding.

If we stopped funding libraries, the middle class would suffer a little bit because they'd have to spend their own money on the books. The poor would suffer a lot more because they wouldn't be able to afford the books.

The last point for me is the most compelling: maybe the middle class use the libraries more, but their existence matters vastly more to the poor who use them.

So services can get messy. But when it comes to tax and benefits, we all agree that what's progressive is fair, right?

Right?

Well, not quite.

Student Loans

One of the best examples of where progressiveness contradicts people's innate sense of fairness is student loans - and, in particular, the interest rates.

Back in the New Labour years, student loans were offered on an inflation-only interest basis: your interest rate was the inflation rate. This meant that, in real terms, no-one paid back more than they paid in (and many, of course, paid less, if they never earned enough to pay back the full loan).

But then, when fees were increased to £9,000 under the Coalition Government, higher interest rates were also imposed. Higher earners were charged interest at up to 3 percentage points above inflation - and all borrowers, while they were studying, had to pay this higher rate of inflation + 3%. This was a progressive move: more interest means more debt to pay back. For low earners, who've never pay back the original sum anyway it would make no difference, but higher earners would end up paying more(6). A table from a 2017 report sets this out:

The trouble is, people hated it. Eye-wateringly high interest rates were regularly criticised in the media, by papers of all political stances. When I've been canvassing door to door they were the most commonly cited complaint about student loans - and they're the only part of the student finance system I've ever overheard people complaining about on the train. When I was a SpAd in Government, high interest rates were the only part of the student finance system to result in the Department for Education coming under serious pressure from No. 10 to do something.

The worst part was, it got people coming and going. When interest rates and inflation was low, people were outraged students were being charged 5% or more in interest when you could get an unsecured bank loan - never mind a mortgage - for less than this. And when inflation shot up, potential interest rates of over 10% hit the headlines. Polling for the Government in 2019 showed that the headline fee rate and the interest rate were the single two most important elements to most people, that they wanted to see reduced and were not willing to trade off for other priorities(7).

This is greatly frustrating to many wonks in the higher education system, who saw the high interest rates as an elegant solution to make the system more progressive - or who became frustrated at the focus on the headline rate. But perceived fairness doesn't always neatly follow what's progressive. And high interest rates made an unpopular policy even more toxic - particularly when they led to young people on good salaries seeing their loan balance go up every year, as the interest was more than they were paying back.

While I was in Government, the Government carried out a set of reforms which abolished real interest rates for all new borrowers, starting with those who started this year, in September 2023. From now on - at least until the system is changed again - students will be charged no more than inflation on their loan balance, meaning that no-one will ever pay back, in real terms, than they've borrowed. This has been welcomed by some, but criticised by others, who complain that the change is not 'progressive' in a formal sense. They are correct, in that it has ended a system in which the richest graduates were being gouged the most by the previous system, that the new system is less, technically speaking, progressive. But it's likely to be seen as fairer.

To be clear, the system is still progressive. University is still free at the point of entry, loans are only repaid as a proportion of salary above a threshold (£25,000) and those who don't pay back their full loan after 40 years have the balance written off. It's just not as progressive as it was.

Now, a lot of the people who work in and around universities are left-wing to a greater or lesser extent, so it makes sense that they'd want to make anything they can, including the university finance system, as progressive as possible. The trouble is, when the mechanism of doing so is as unpopular as high interest rates are, the price of making the system more progressive is to make it significantly more toxic. And what happens when you make tuition fees more toxic? Well, we can see that quite clearly: over the last decade, tuition fees have only gone up once - meaning that the money universities receive per student from fees is now worth less than £7,000 in 2012 prices(8). The more toxic the system, the less likely politicians - of any party - are to put more money into it by raising fees.

The fact is, we already have a very effective method of progressive taxation - it's called income tax. There are some progressive elements of the student finance system that are widely supported and serve valuable purposes - such as the fact that fees are not paid upfront making university available based on merit, rather than wealth, or the way that repayments are contingent on income. Rather than toxifying the university funding system to make it even more progressive, those on the left would be better advised to simply support higher rates of income tax(9).

Inheritance Tax

If the interest rate on student loans is a sector preoccupation, attitudes to inheritance tax are the bete noire of progressive advocates. Why is a highly progressive tax, that only 6% of people will pay - and even then, only when they're dead - so heartily disliked? There's a lot of cope in this space, with people suggesting that people don't realise how unlikely they are to pay it, but recent polling shows this isn't the case.

Now, popular opinion about what's fair isn't the only thing we should take into account when thinking about tax - and now is how progressive it is. We should definitely be thinking about deadweight loss: how much useful economic activity will be lost if something is taxed more (or that we might gain if we tax it less). We should think about whether what we are taxing is something we want to encourage (like R&D) or discourage (like CO2 emissions) and try to tax the latter more than the former. We should consider whether it is inflationary. We should think about how much it might raise - and how easily it can be collected and evaded. But particularly when thinking about personal taxes, perceived fairness is a relevant factor.

And inheritance tax really is seen as unfair:

Recent polling by the Tax Policy Associates sought to probe whether this changed when you told people how few were going to pay it. They divided their panel into two statistically balanced groups, the first of whom were asked the questions straight, the second of whom were told, “For most married couples, inheritance tax is only charged where their net assets exceed £1m. The rate is 40%. Do you think IHT is fair currently?“

The first group, unsurprisingly and consistent with other polling, thought it was unfair:

But the second group also thought it was unfair:

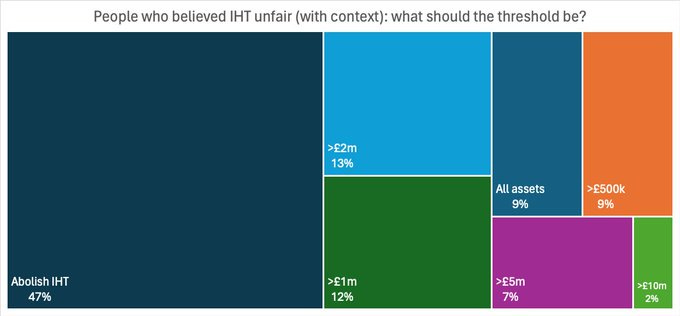

It made a difference, but not enough - a clear majority (c. 60:40) of all voters continued to think it was unfair. And when they probed whether people just thought it should be charged at a higher rate, almost half opted for abolition - and nearly all the rest for significantly higher thresholds.

This is surprising, but also consistent with polling for Ipsos Mori this year that shows it's seen as the most unfair tax. People really, genuinely, don't like the concept of taxing what someone passes on to their family after death.

So, what's a good progressive to do?

The answer, surprisingly, is not to worry. Because even though people think income tax is fair and inheritance tax is unfair, when asked what they'd prioritise cutting they choose...income tax.

Although counter-intuitive, this shouldn't actually be that surprising. If we think of our daily lives, we can all think of particular bugbears that we feel are deeply unfair - but that don't actually make much difference to us. While there may be other things which make a much bigger difference to us that we'd prioritise.

To give a tangible example, personally I feel it's unfair I have to pay extra to get garden waste collected - it should be a standard service. It annoys me every year when I fill out the green bin form. On the other hand, I feel my council tax is pretty fair: I live in a nice house, can afford to pay, the Council does a pretty good job and there are a lot of services that need paying for. But while I may moan about the green bin charge more, give me a choice of abolishing the green bin charge or a 10% cut in my council tax, I'd choose the latter in an instant!

The public aren't fools. They know there's only a certain amount of money available for tax cuts - and when given the choice, they prioritise those that affect the most people, and the lower paid. It suggests the Government got it right by choosing to cut National Insurance(8), not Inheritance Tax in the recent Autumn State - and not just on progressive, utilitarian grounds, but on popular support, too.

Rather than flogging the dead horse of trying to persuade people that inheritance tax is unfair, progressives would be better to roll with the punch and lean in to the fact that, when push comes to shove, most people have higher priorities.

And finally

There's a danger with this sort of post that by focusing on the exceptions one can give the wrong impression. Don't get the wrong idea: in most cases, when dealing with tax, benefits and other fiscal measures, what's progressive is seen as fair. It's a great starting point - but it's also important to remember it doesn't always work.

If people don't see a policy measure as fair but it's nevertheless important, then one must make the case for it. Corporation tax is not a 'costless tax' even if it is often perceived as such - we all pay in the long term in terms of reduced business investment, reduced growth and worse jobs. The case for lowering corporation tax is not based on public opinion, but on long-term impact.

But when one is trying to make a system fair - listen to people if they tell you it's not. Don't keep insisting a technically progressive measure is fair, if people don't think it is - nine times out of ten you'll achieve nothing but to make your overall system less popular. Most of our fiscal system is progressive; not every part of it has to be. Ultimately, a progressive income tax and benefits are the optimal way to debate the level of redistribution we want - for everything else, functionality and fairness are the priority.

If you enjoyed this post, you can help by sharing what I write (I rely on word of mouth for my audience). You can also ensure you never miss a post, by entering your email address into the subscription form below.

(1) I went to see hockey and one of the athletics heats sessions, a highlight of which was seeing Mo Farah(2) qualify for the 5000m.

(2) I initially wrote that I had seen Mo Mowlam qualify for the 5000m, which would have been even more spectacular.

(3) We are not using progressive here as a synonym for 'left wing' or 'socially forward looking' but in its more technical sense.

(5) In practice there are numerous parts of the income scale which have marginal tax rates significantly higher than this due to withdrawal of benefits, student loan payments or removal of personal thresholds; however, the 50% headline figure appears to be have a symbolic element to it.

(6) It actually had an unfortunate horseshoe effect, whereas those in the middle, who earned enough to pay it back at some point, but only after 20-30 years, would pay the most while those at the very top - investment bankers, for example - who could pay it back in just 5-10 years would pay less. But overall it was progressive.

(7) Attitudes towards the Student Finance System (2019)

(8) This may also have occurred due to the removal of number controls, meaning almost all the extra funding that has gone into HE has gone to increasing the number of places, with each place funded less well. But the fact that no major party will even contemplate raising fees is telling - and suggests that detoxifying the system should be a priority for the university sector.

(9) Or a wealth tax, if that's your poison. After all, as Tony Benn said, we should tax people because they are rich, not because they are educated.

(10) Cutting NI is largely equivalent to cutting the base rate of income tax, with the exception that NI is only paid by working people, not pensioners - as such, the tax cut benefits working people more.