For the 98%

A government should stand for the central majority

There’s a well known slogan, ‘For the 99%’, that argues for focusing on the needs of the majority, not the wealthy 1% at the top.

The top 1% make more of a contribution than many realise - not least, by paying 29% of income tax - but, nevertheless, the sloganeers have a point. While we shouldn’t demonise or persecute the wealthiest, it’s probably right that most of government’s efforts shouldn’t be focused on organising society for their benefit.1

But what about the bottom 1%? How much should society be focusing its efforts on this group, at the expense of the 98% in the middle?

A study in Sweden found that 1% of the population commit 63% of all violent crime. In the UK, prolific offenders - a group comprising around 550,000 people, or just under 1% of the population - received half of all convictions between 2000 and 2021. Of course, for young offenders, or those on their first time offence, we should do all we can do create an environment that supports rehabilitation. But for the hardened criminals, for how long should we keep up such expensive efforts? When individuals such as the Manchester Arena bomber, or Axel Rudakubana, the Southport murderer, assault prison guards - because their ‘human rights’ say they must have access to kettles, and hot boiling oil - how much must we spend indulging such antics? How many more must die for Axel?

Walk into any state secondary school today - and more than a few primary schools - and you will find multiple children who are assigned a permanent, exclusive, teaching assistant for their support. Why do these children deserve 1:1 tuition, when the majority are taught in classes of 31 or 32?2 Why should our extreme reluctance to expel the worst behaved lead to children having to sit in the same classroom as a child who has drawn a knife on - or sexually assaulted - them?3

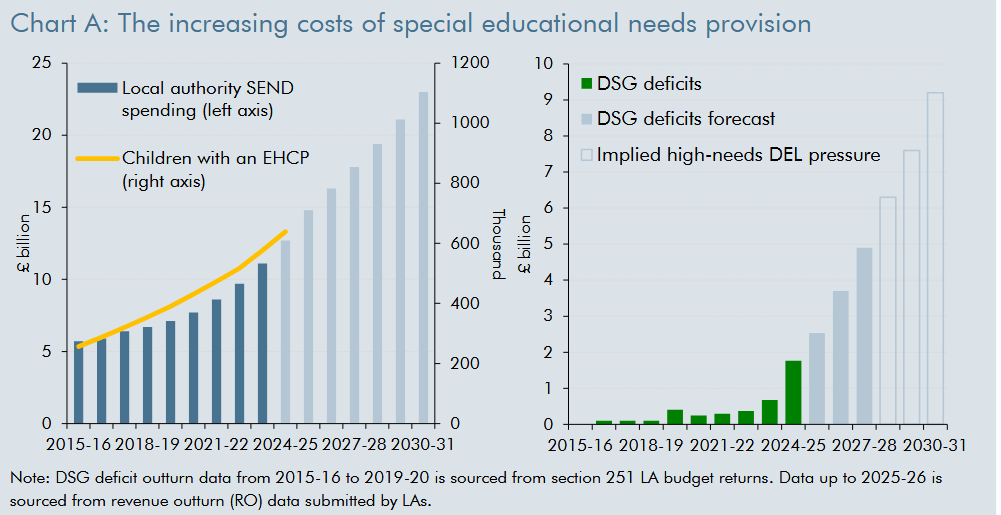

As I’ve written before, the proportion of students diagnosed with SEND, or issued with EHCPs, is sky-rocketing - with spending doubling over the last ten years. And yet educational outcomes for SEND have not improved.4

The average cost of a placement in an independent SEND school is £61,000 - or around seven times more than it would cost in an ordinary state school. Of course, no child should be written off - we should spent at least the same on the most vulnerable child as on the average, and probably more, maybe even 2 or 3 times as much. But 7 times as much, or more?5 I know of multiple cases where well over £100,000 is being spent on a single child - a sum of money that, if spent on a music and a PE teacher at a local comprehensive, could provide enrichment opportunities for over 1000 children a week.6

And remember, when schools increase their class sizes, or cut back their music and drama departments because of ever-increasing spend upon the 1%, it is not the wealthy who suffer most - their can afford private music tuition, or extra tutoring. It is those children who depend upon the state for their education who really lose out.

Similarly, it is right that we seek to support the homeless. But when someone has repeatedly turned down society’s support, rejected shelters and rehabilitation again and again, should we spend an unlimited amount to keep trying to reach them? Why should recovering drug addicts or the unemployed houses in social housing in central London, when ordinary workers have been priced out, and must spend an hour or more commuting in? Why are asylum seekers who have illegally entered our country housed in the hotels which were once the special locations in which communities celebrated weddings or anniversaries?

There are two ways in which an undue focus upon the bottom 1% can harm the broader majority.

The first is by directly degrading the common realm: the badly behaved child who disrupts the learning of 30 others; the shoplifters, operating with impunity, that result in steaks being security tagged and shops driven out of an area; the drug addicted vagrants permitted to take up occupancy in parks and common areas.

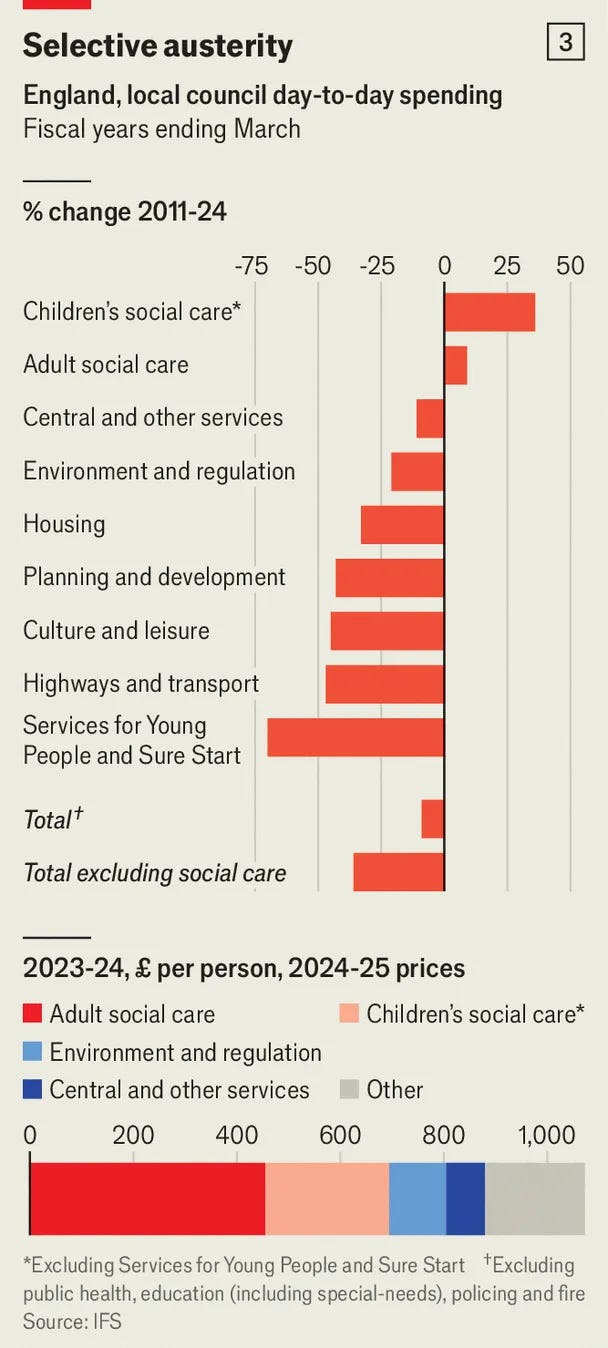

The second is by absorbing a disproportionate amount of money, such that funding begins to be stripped from services for the general public.7 This is less obvious - but over time can have a disproportionate impact.

In today’s Britain, through a combination of well-meaning policies, statutory obligations and human rights committments, we have created categories of people who are automatically jumped to the front of the queue, and upon whom arbitrarily large amounts of money must be spent to meet their perceived ‘needs’ - regardless of how much there is in the budget, or the needs of the majority. The result is an increasing strain upon the working majority, whether in the form of higher taxes, reduced household incomes or the steady degradation of the public realm.8

It’s more like ‘for the 80-90%’

Those who use the slogan ‘for the 99%’ are frequently in favour of policies that target a broader definition of the rich, such as taxing private schools.9 And in the same way, ‘for the 98%’ should be interpreted, in some cases, as being for the central 80-90%.

In 21st century Britain, two people on the 10th and the 90th percentile have more in common than ways in which they differ. They both use state schools and the NHS. They are not criminals, but nor can they shield themselves away from crime in gated communities with private security. They depend on work for their principal source of income, not inherited wealth or benefits.10 They will shop, at least some of the time, in Tesco and WH Smiths11, they will use public transport and drive on the same roads, their children will play in the same parks and playgrounds.

Of course, I am not saying that money does not matter, or that it is not better to be on the 90th percentile than on the 10th. But the commonalities are extensive.

This is not an inevitability. It was not such for most of British history. It is still not the case in many developing countries. In the Philippines, where I lived for almost three years, those on the 10th and 90th percentiles live in separate worlds - meeting only if it is in a service arrangement. They certainly would not drink in the same pubs, use the same public amenities or have their children attend the same schools.

There is a saying a society should be judged on how it treats the most disadvantaged. Like many such sayings,12 it sounds noble, but is deeply flawed in practice. Some of the most disadvantaged are there as a result of their own wilful and unrepentant actions. Even when deserving, some of the most disadvantaged are effectively utility sinks, upon which arbitrarily large sums of money can be spent without seeing meaningful improvement.13

Instead, we should judge our society on how it treats the ordinary man, woman or child.

We need a Government that focuses relentlessly on improving the lives of the central 80-90%. That doesn’t mean demonising or persecuting the top - and nor does it mean writing off the bottom. But it does mean putting the welfare of the central majority first, and not constantly subsuming them to the needs or interests of the top and bottom.

There is something deeply unhealthy about a society which guarantees free dental care to illegal immigrants while half of its own citizens - including many children - are unable to see an NHS dentist.

I want an economy that is run for the hard-working majority, giving good jobs to those will work, and where those who are out of luck get support - not run for the benefit of long-term benefits claimants. I want employment rules that ensure hard-working employees are treated fairly, not that shield malingerers and trouble-makers.

I want money for public services poured into schools and other public services in a way that will benefit the majority, not increasingly diverted to the high cost needs of the fewer than 5% who can claim high-cost SEND. I want classes to be run for the benefit of the majority, not the 2-3 serial disruptors who ruin it for others.

In maintaining the public realm, I want the police, government and local authorities to prioritise the needs of the law-abiding majority, not drug addicts, criminals and vagrants. Hotels should be for residents, not asylum seekers, who should be housed well away from residential communities.14 Parks should be safe places, libraries and playgrounds maintained, bin collections regular and shop-lifting punished.

Britain is not as rich as it would like to be. We see the mass dissatisfaction with the status quo in the deep unpopularity of Starmer and Sunak before him. We can continue to devote ever-increasing efforts towards the ‘hardest to reach’ and the ‘most disadvantaged. Or we can give these people their fare share and return to the task that we should never have abandoned: the improvement of the common weal and the restoration of the public realm.

Society should not be focused around the interests of those at the very bottom, any more than it should be around those at the very top.

See also:

Though yes, we do want to be attractive to entrepreneurs, to make Britain a good place to do business, and to not drive the wealthy away.

Eldest is in a class of 32.

With both prisons and schools, tolerating this sort of behaviour from the 1% in schools makes it harder to recruit and retain good staff.

Given that we are now classifying a much larger and more able cohort as SEND, this means that in practice they have in fact deteriorated.

You may ask, do I not support some form of special programmes to look out for the top 1%, the most academically able? And yes, I do. But one of the most expensive interventions I’m aware of - the specialist maths sixth forms - receive around 20% more funding per pupil, around half the cost of an average state-school SEND placement and 1/6 that of an independent placement. Similarly, in a normal comprehensive, whatever science clubs or gifted and talented programmes exist pale in comparison to the cost of a 1:1 teaching assistant.

Many people in and around education seem to be attached to a belief that we are still in the 1950s, and worry that we will take all the funding away from the least advantaged and spend it all on the most able. As can be seen from the stats, this is approximately as justified as Mr. Bumble the Beadle’s concern that he might be feeding the orphans too rich a diet.

At least 20 lessons or extra-curricular activities, each with 30 children.

Or taxes have to be raised.

In many cases these policies, duties and obligations are fiercely defended by the most privileged in society, who are largely shielded from the consequences, in a form of How Elite Benevolence hurts the middle.

For the 94% just doesn’t have the same ring.

Of course, many in this middle majority will receive some benefits at some point - particularly if one includes benefits such as child benefit - just as many will receive some form of inheritance. But those who are long-term unemployed are only 1% of the population (with perhaps another 1-2% on long-term disability).

At least, before it closed.

‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’, for example.

No-one would deny that children in care have been dealt a rough hand in life and that they deserve our compassion and support. And indeed they do. However, Government persists in arguing that their outcomes should be the same as the average child - for example, worrying that they are less likely to go to university.

This is a group of people of whom 27% suffer from fetal alcohol syndrome, a condition that causes lifelong brain damage - not to mention the countless other problems of abuse and neglect. Of course they will be less likely to go university! They deserve our support - but when one sets up goals that are not based in reality, one justifies the spending of unlimitd money and warping of other policies in the service of reaching unattainable goals.

Or, indeed, deported.

Great post. I don't know whether you had John Rawls' difference principle in mind when writing this piece, but there's a clear link to his idea that inequalities should be arranged "to be to the greatest benefit to the least well off". He's the philosophical loadstar for many on the left, but as you rightly point out, in practice this comes at the expense of the median person's welfare.

Isn't the problem that we expanded the definition of SEND far beyond the 1% who are severely impaired? Currently, 1 in 5 children in England are classed as disabled, in the past it might have been closer to 1%.

Likewise, should we spend less healthcare on the '1% with severe chronic illnesses and more on the 98% with milder conditions? Should we spend less on the 1% with severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia and more on those with mild anxiety and depression?

In many ways the direction of travel is spending much more but on those with less need. Be careful what you wish for!