What will happen at the 2029 General Election?

Five scenarios explored using a fragmentation model

What will happen at the next General Election?

Honestly? No-one knows.1 In 2010, after Cameron had failed to win a majority, few would have thought we were heading for 14 years of Tory rule. In October 2021, Boris Johnson was still ‘squatting like a gigantic toad’ across British politics, supreme and unassailable. He was out of office within a year, and the Conservatives out in their worst ever defeat within three.

But while predicting the future is hard, we can explore what might happen. Scenarios allow to do this - offering not predictions, but possibilities, and helping us to think about what would need to happen to bring each one about. In this piece we’ll be using a simple fragmentation model to examine five scenarios showing what might happen at the next general election2:

Labour Hegemony

Starmer Scrapes By

Tories Triumphant

The Centre Cannot Hold

Rise of the Right

But first, what happened this July?

Several things happened at the General Election held on 4 July:

Labour won a very large majority (174 seats). This majority was won on a relatively small proportion of the vote (33.7%; compared to the 43.2% won by Tony Blair in 1997, for a similar sized majority).

The Conservative vote share utterly collapsed, from 43.6% to 23.7%. They were reduced to 123 seats, their worse election result in modern history.

The Liberal Democrats, Greens and Reforms all surged.

Voter turnout collapsed from 67% to 60%.

Other relevant things included the SNP collapsing in Scotland, and four independents, plus Jeremy Corbyn, winning seats on pro-Gaza platforms.

While the scale and significance Labour’s victory cannot be denied, it is fair to say that it was more of a vote against the incumbent Conservative Government - and that many voters declared ‘a plague on both your houses’ by staying at home or voting for parties outside the big two3.

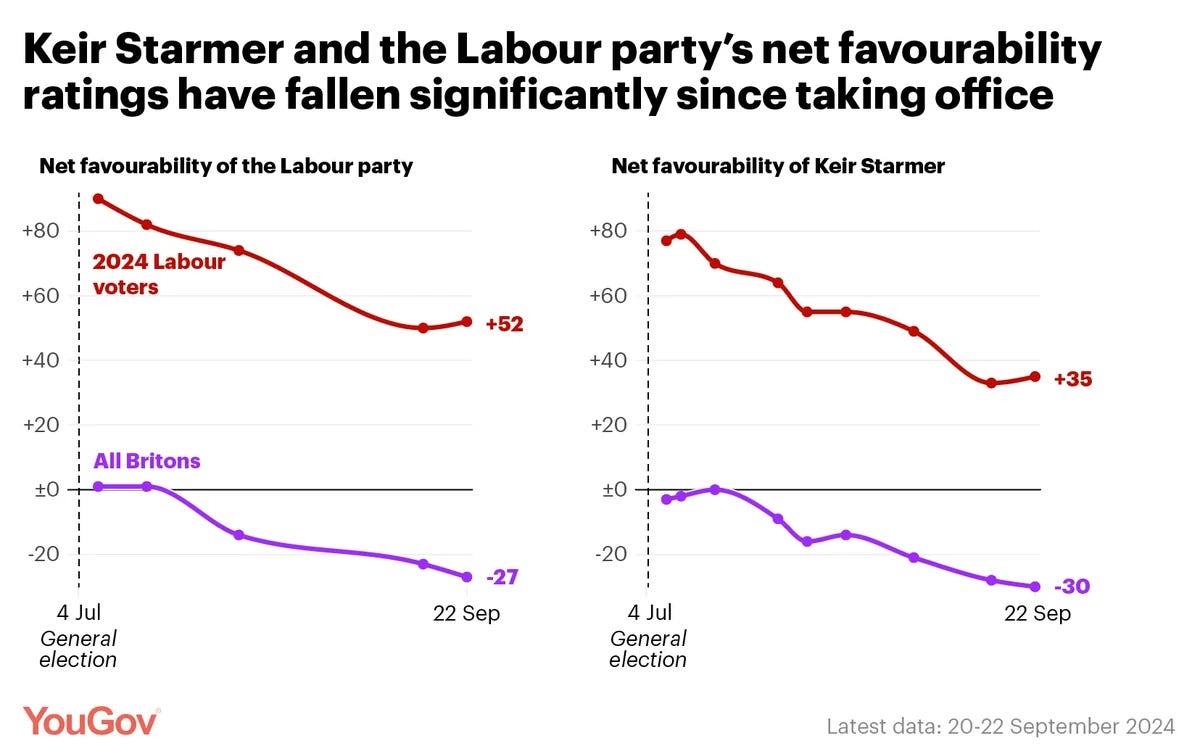

Since the election, Labour has had a challenging summer, marred with stories about senior members of the Government accepting gifts from donors, infighting in No. 10 and controversy over the decision to means-test winter fuel payments. Both Starmer and the Labour party have seen their opinion ratings drop dramatically - at a level much faster than is common for a new Government.

Similarly, a recent opinion poll by More in Common, one of the most accurate pollsters in the recent election, showed Labour falling to below 30% - though the Tories are not yet benefiting from this.

At one level, opinion polls are pretty meaningless this far away from a General Election - a lot can happen between now and 2029. But the combination of a large but shallow majority, three challenger parties to the main two and increased electoral volatility creates a high degree of unpredictability. Forty years ago, we’d have said that a party winning a majority the size of Boris’s in 2019 - let alone Starmer’s this year - would be in for at least two terms. But now, anything could happen4.

The Fragmentation Index

We’re going to take two of the major things5 that happened in the recent election to construct two indices. We’ll then use this tool firstly to look at past elections and then, more interestingly, to explore five scenarios for 2029.

The two indices are:

The Lab/Con Index. This measures the relative strength of the Labour and Conservative vote shares. It is equal to zero when the Labour and Conservative vote share is identical, 1 when the Labour vote share is 0 and -1 when the Conservative vote share is 0. It can be thought of how well Labour does compared to the Conservatives, or vice-versa6.

The Fragmentation Index. This measures what proportion of the vote share that Labour and Conservative party, combined, get. It is constructed so that it equals 1 (fully consolidated) when Labour and the Conservatives combined get 100% of the vote, and -1 (fully fragmented) when Labour and the Conservatives combined get 40% of the vote7. It equals 0 when Labour and the Conservatives get 2/3 of the total vote, or twice as much as all the other parties combined8.

Let’s use these to look at some recent general elections, as well as the historic Attlee and Thatcher wins of 1945 and 1979:9

We can clearly see which party won each election - with bigger wins being further from the central axis, as we’d expect.

There is also a clear, though not monotonic, trend in increasing fragmentation. The two historic elections (1945 and 1979) are much more consolidated than most recent ones. Some more modern elections - notably 201710 - are quite consolidated, but in general more recent elections see more fragmentation, with 2024 the most fragmented election at all. Interestingly, looking at only Labour victories, we find that each election is more fragmented than the one before.

So what might happen in 2029?

One can think of potential reasons why any of the parties could do well:

Labour: Between 2010 and 2019, the Conservatives increased their vote share at each successive election - despite being initially elected on a relatively low share at a time of financial difficulties. If Labour do well, and people feel the country is on the right trajectory, there is no reason why they shouldn’t do the same.

Conservatives: In both 2017 and 2019 the Conservatives won over 40% of the vote. This year many people voted against the Conservative Party, out of anger at Partygate or more broadly feeling it was time for a change. As anger fades, and Labour has to make difficult decisions, many of those voters might return.

Liberal Democrats: The Lib Dems have 72MPs, a strong presence in local government and - as they are not in power - no need to make unpopular decisions. This feels like a strong position to build from11.

Reform: Reform won 14.3% of the vote but only 5 seats. It is now professionalising and turning into a proper party. They are second in 98 seats, 89 of them Labour - including many working class, post-industrial seats. These votes may be unlikely to vote Tory again in the near future - but they might vote for an anti-immigration, party that takes populist economic stances - such as Reform.

The Greens: The Greens tripled their vote share and showed they could win both progressive city seats and rural Tory ones. They are second in 40 seats and their local presence is growing. Polls consistently show that more people would vote Green if they thought they had a chance at winning - this year’s breakthrough could be the moment that persuades many more to do so.

All sound plausible, right? But a moment’s reflection will tell us that not all of them can come true.

That is the purpose of scenarios: not to predict the future, but to give us a lens for contemplating it. Each distinct scenario gives us a framework to think how, and under what circumstances, it might come about - and therefore how to either help it happen, or to prevent it12.

How did I calculate each scenario?

For each a scenario I defined a value for each index. I then used these to calculate a vote share for each of the two major parties, and then adjusted the vote share of each of the other parties up or down accordingly, so the total vote share summed to 100%. Following this, I used Professor Ben Ansell’s 2029 General Election Predictor App to turn these vote shares into seat predictions13.

I made a number of simplifying assumptions:

I assumed that each minor party gained or lost vote share proportionally to its current vote share. I.e. all minor parties gained or all minor parties lost.

I used a proportional swing to turn vote shares into seats.

I assumed the vote share of the Northern Irish parties, Plaid Cymru, minor parties and Independent candidates stayed constant at 7.2%14.

These are almost certainly overly simplistic.15 one can imagine all sorts of circumstances where they are not true:16 perhaps one of the parties gets enmeshed in scandal, or a thermostatic effect due to Labour being in power whereby Reform gains while the Lib Dems and Greens fall back. Reform and the Greens will almost certainly target their efforts in specific seats, rather than aim for proportionate growth everywhere.

But nevertheless, even with these simplifications, the model provides us with a powerful tool with which to begin examining possibilities for GE2029.

Are we at the scenarios yet?

Yes! Here we go:

Labour Hegemony

Starmer Scrapes By

Tories Triumphant

The Centre Cannot Hold

Rise of the Right

And here’s how they look on the scatterplot:

Let’s examine them one by one. For those who prefer not to read it off the chart, the current situation is Con/Lab index -0.17; Fragmentation Index -0.32; Labour majority 17417.

Labour Hegemony

(Con/Lab Index: -0.18; Fragmentation Index: -0.1, Labour majority 196)

After a rocky start, Labour moves into delivery mode, taking a series of tough decisions. For two years things are tough, with them falling to record lows in the polls - but by 2027, the hard choices begin to pay off and people start to feel their lives are getting better. Growth accelerates, household incomes begin to rise and the cost of living crisis is a distant memory.

As people begin to see visible signs of improvement in public services, the Labour vote begins to return. Some former Tories who had ‘lent’ their vote to the Lib Dems and Greens decide that this time they trust Labour enough to vote for them. Labour relentless hammer home the message that the country’s challenges were due to ‘14 years of Tory misrule’ - and it sticks. Against this backdrop the Conservatives struggle to rebuild. They claim a few votes back from Reform, and a few from the Lib Dems, but not enough - and Labour romps home with an even larger majority than before.

Conservative 26.1 Labour 37.6 Lib Dem 10.0 Green 5.3 Reform 11.7 SNP 2.118

Starmer Scrapes By

(Con/Lab Index: -0.08; Fragmentation Index: -0.3; Labour majority 50)

At the October Budget Labour makes a number of tough decisions, hoping to get the bad news out of the early and lay the seeds of better things to come. But despite the sacrifices, growth stubbornly fails to come, held back by the UK’s high debt and a global economic environment that appears to be one shock after another. There’s no disaster, but jam always seems one more year away.

Despite this, the Conservatives fail to capitalise on this unpopularity. Their new leader fails to make the impact they had hoped for; in desperation, they choose a new leader in 2026, but it’s too little too late. They pick up some seats from Reform and the Lib Dems; meanwhile, Reform makes gains against Labour in the midlands and north - though not by enough to break through. Labour limps into the election only barely above 30% in the polls - but against a lacklustre Tory party, it’s enough to secure a victory.

Conservative 26.7 Labour 31.4 Lib Dem 12.0 Green 6.3 Reform 14.0 SNP 2.5

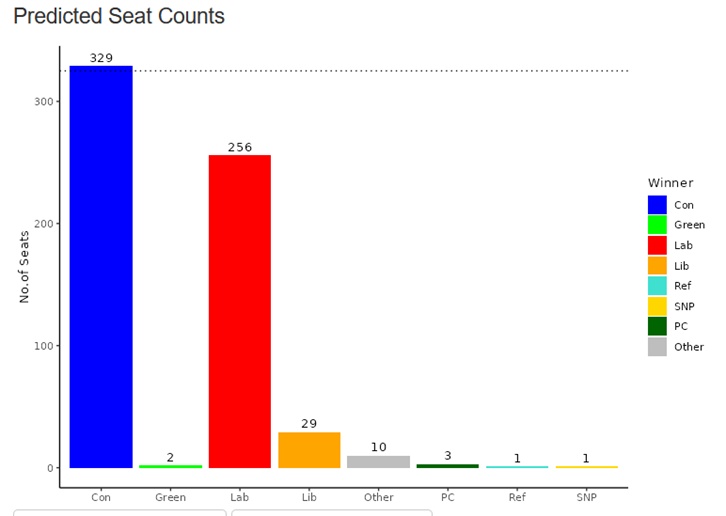

Tories Triumphant

(Con/Lab Index: 0.1; Fragmentation Index: 0; Conservative majority 819)

Labour’s rocky start continues, with a slew of unpopular decisions sending their popularity plunging. The new Tory leader capitalises on this effectively, connecting with the public in a way which Labour never fully recovers from. As voters abandon Laboutr, the Conservatives consolidate their former vote, picking up about 5 percentage from Reform, and another 5 percent from the Lib Dems - and even a few from Labour itself, as tax rises and low growth begin to bite.

The economic situation does improve, a little, and Labour is able to recover from its nadir, aided by the fact that some voters still do not want to see the Tories back in power. The smaller parties are squeezed - but on the day the Conservatives squeak over the line, seventy seats ahead of Labour.

Conservative 36.7 Labour 30.0 Lib Dem 9.0 Green 4.7 Reform 10.6 SNP 1.8

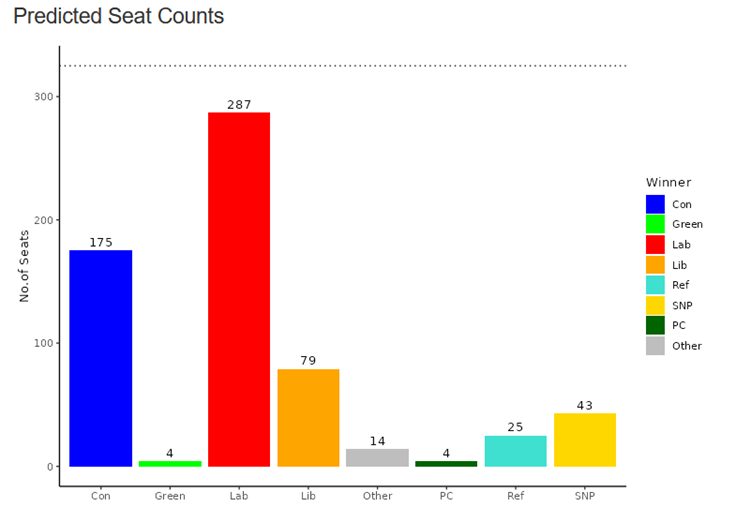

The Centre Cannot Hold

(Con/Lab Index: -0.05; Fragmentation Index: -0.7, Orange Coalition with combined 62 majority)

Labour takes all the tough decisions - but the good news never comes. The promised growth never comes, living standards continue to fall - and immigrants continue to come across the Channel. Every winter sees another NHS crisis; every budget another round of tax rises and spending cuts. Labour’s opinion ratings fall, and keep on falling, as they experience the ruthlessness of the electorate towards the incumbent.

But if Labour is hated, the Tories are hardly less so. Memories of Partygate and the Minibudget die hard with no recovery - and repeated Labour scandals mean the public see the major parties as two bad peas in a pod. Reform surge in Labour’s northern heartlands, the Lib Dems tighten their hold on the Blue Wall and the Greens pick off vulnerable seats here and there20. Though the final vote shares are tight, Labour’s vote continues to more efficiently distributed and when the dust settles it is the largest party - though well short of a majority. With trepidatious memories of 2010 but telling themselves that this time it will be different21, the Lib Dems agree to join them in Coalition.

Conservative 22.5 Labour 24.9 Lib Dem 15.6 Green 8.2 Reform 18.3 SNP 3.2

Rise of the Right

(Con/Lab Index: 0.15; Fragmentation Index: -0.6, Conservative-Reform confidence and supply agreement22)

Buffeted by scandal, Starmer’s ‘Government of Service’ never gains traction with the public - particularly after a wave of tax rises and spending cuts in the October Budget. Even more damaging, however, to Labour’s reputation are increasing waves of immigration, with Channel crossings up and legal migration - after an initial fall - steadily creeping up, in an aim to create the growth that never seems to come.

Seeing an advantage, the Conservatives campaign heavily on the matter, winning back some former supporters, as well as others who had sat at home. Reform is equally active, however, and even as they lose voters back to the Tories in the south, they surge forward in the seats in which they are second to Labour, combining anti-immigration rhetoric with populist opposition to spending cuts. The SNP regain their dominance in the north while the Lib Dems sit tight in their new-found strongholds, their voters equally repelled by both Labour and the Conservatives. After the election, the Conservatives have done well, though still short of a majority. Though he refuses to join a coalition, Nigel Farage agrees to support the Conservatives in a confidence and supply agreement, meaning the Tories reenter Downing Street.

Conservative 28.8 Labour 21.3 Lib Dem 14.8 Green 7.7 Reform 17.3 SNP 3.0

So what does all this mean?

As I have said, these are scenarios, not predictions. Perhaps some are more likely than others but all, to my mind, are plausible - none see the Conservatives recover to above their 2017 or 2019 vote shares, nor see Labour fall as fast or as hard as the Tories did between 2019 and 2024. There are further scenarios we could explore - including ones where we see a renewed consolidation of the vote back to 1997 or 2017 levels23 - or of course ones where Reforms gain and the Lib Dems and Greens shrink - or vice-versa. We live in an age of increasing volatility and unpredictability.

For those involved in the business of politics, they may provide something of a guide - not a marked trail, or an infallible path to follow, but perhaps a map of the terrain that lies ahead, waiting to be navigated.

Except Cassandra, and you wouldn’t believe her if she told you.

Which I’ve suggested will be in 2029, but of course it could be any time; 2028 is certainly a strong possibility if Labour think they are ahead.

This is itself an achievement for Labour in managing to appear moderate. In 2017 and 2019, when voters were more opposed to Jeremy Corbyn, voters were much less willing to vote for third parties. Many people who voted for the Liberal Democrats did so in the knowledge that they were comfortable with Keir Starmer becoming Prime Minister.

Well, within reason.

We’ll set aside voter turnout.

For those who like formulae, the Lab/Con index = (C-L)/(C+L), where C and L are respectively the Labour and Conservative vote share.

On the grounds that at this point - assuming there are three significant minor parties - there are effectively no ‘major’ parties any more, with the average of Labour + Conservative no more than the average of the other parties combined.

Let Av(Main) = (C+L)/2. Let Av(Other) = 100 - (C+L)/2. Then Fragmentation Index = (Av(Main) - Av(Other))/(Av(Main) + Av(Other)).

This is my first time using Datawrapper and I am now kicking myself for not having used it before.

Which saw both a polarising Labour leader in the form of Jeremy Corbyn, and the collapse of the major secondary party on the right, following the Brexit referendum.

One interesting point is that the Lib Dems performed extremely efficiently, winning a very similar proportion of seats as their vote share (ironic, given their long-term championing of PR). However this means that they are now second in only 27 seats - compared to 40 for the Greens and 98 for Reform. The latter two parties - who won only 5 seats each - will therefore potentially find it easy to grow that number.

Depending on your preference!

The size of Northern Ireland is not going to change, but this is perhaps more problematic for the pro-Gaza independents - this group might completely collapse (perhaps most likely) or grow even further.

Though not as simplistic as the mainstream commentary on election night which tends to focus overwhelmingly on ‘swing’.

The model is particularly weak in Scotland, where the assumption that the SNP move in lockstep with wider fragmentation is not really justified.

Right now it’s a bit less because they kicked out some members for rebelling against the King’s Speech. But it was 174 the day after the election.

Note that I am using UK vote shares, to be consistent with those I quoted above and used in historic elections. Prof. Ansell’s app omits Northern Ireland and the Speaker, so these vote shares need to be adjusted by a factor of 0.975 in order to get the seat totals shown in the chart.

The working majority would be higher, due to Sinn Fein and the Speaker. That’s true in the previous scenarios too, of course, but this was the first one where it seemed to matter!

I am unsure why the seat converter doesn’t model the Greens well - I suspect it is because of their ultra-targeted seat strategy. I’m pretty sure in this scenario they would gain a few seats, perhaps ending up on 10-15.

Because Labour under Keir Starmer would totally be less politically ruthless than the Tories, right?

Depending on how many seats Sinn Fein win, it’s likely the two parties together would have a very small majority - just.

I personally think this is unlikely - but admit it is not impossible.

Interesting and impressively ACX-esque piece of original research. Those indices are an illuminating way of categorising past and potential future elections.

I think turnout will matter more than you suggest. I think it will continue its downward trajectory and there will be even more of a "plague on both your houses" effect, as voters who resented the corruption and/or austerity under the Conservatives and thought Labour would solve it (especially those too young to have known any government but Conservative) realise it's business as usual on both counts and become disillusioned.

This, of course, makes it even more difficult to predict the outcome, as it depends on the views of the shrinking remnant who still vote, rather than of the whole country. I'm guessing it will help the three second-tier parties, as their platforms all have an element of "we represent genuine change" and they haven't had a chance to disprove that. (Although there will probably also be an effect where the remaining supporters of both of the big two parties are the most loyal and dedicated ones, with the more swing-y ones defecting to other parties and the more cynical ones defecting to "none" - which means that of those declaring Con or Lab support in the polls, a higher proportion than usual will actually vote that way.)

I also think Starmer won't last until 2029, with how early and how quickly his approval rating is plummeting and the various bribery scandals surrounding him. I think your "Starmer scrapes by" scenario will actually be "Labour scrapes by with some other leader". (Although you have much more insight than I do into what does or doesn't result in changes in party leadership, which can look a bit arbitrary from the outside, so ICBW.)

“The Fragmentation Index” - Bob Howard goes back to his roots as an IT guy and fixes some slow hard drives.