We too, are elves

Reflections on falling birthrates and 'the Little Golden Age'

This post is the quarterly ‘long-read’ voted for by paid subscribers. To vote quarterly on a topic that I should write about, become a paid subscriber. ‘Founding’ subscribers are also able to nominate topics for the quarterly vote. A big thank you, as always, to all readers and subscribers.

Kings made tombs more splendid than houses of the living, and counted old names in the rolls of their descent dearer than the names of sons. Childless lords sat in aged halls musing on heraldry; in secret chambers withered men compounded strong elixirs, or in high cold towers asked questions of the stars. And the last king of the line of Anarion had no heir.

Faramir of Gondor, The Two Towers, by J. R. R. Tolkien

Fantasy is replete with dying civilisations. Reading them, I always felt them slightly unrealistic. Why did the elves, who were immortal, immune to disease and appeared to want for nothing not have enough children to reproduce themselves? It didn’t seem to be the case that they couldn’t have children1 - they just didn’t. But why?

Tolkien’s elves have many imitators, some of which draw from older sources too, such as Tad Williams’ Sithi. In Michael Scott Rohan’s Winter of the World series it is the duergar - in this case, literal neanderthals - who are dying, the fading remnants of their more advanced civilisation still lingering in caverns underground.2 In the Wheel of Time humanity as a whole is in retreat, with whole nations having vanished and regions that once were settled farmland now abandoned.3

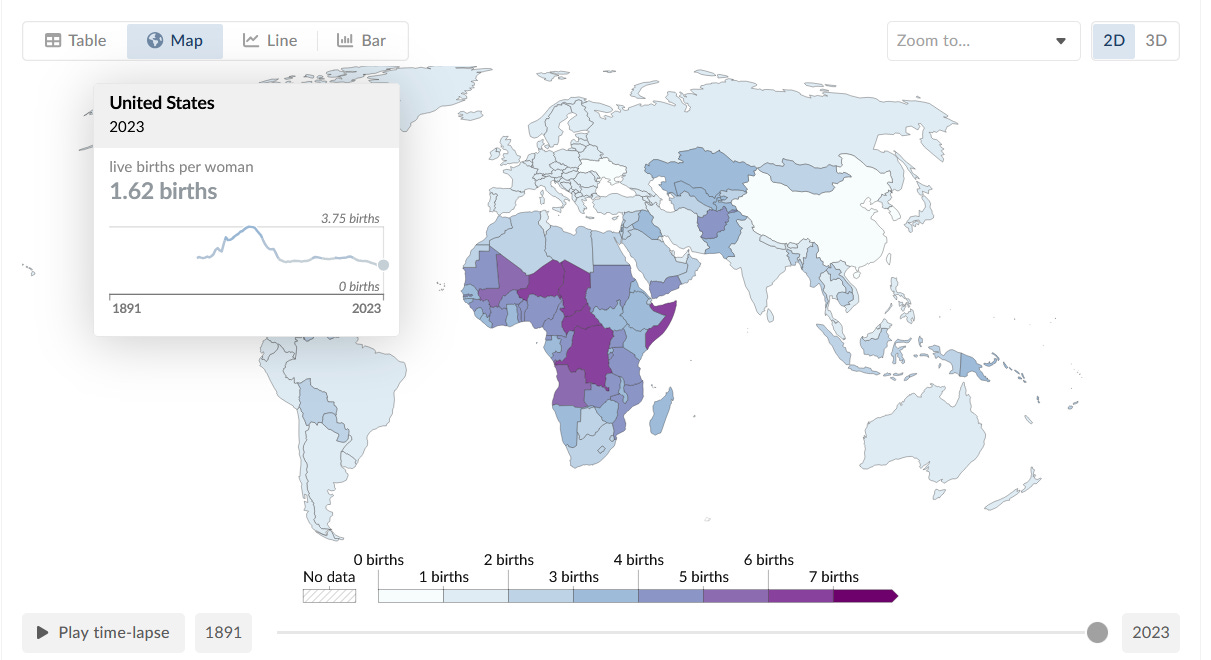

But now we, too, have become elves. At current birthrates, every 100 South Koreans will have 13 grandchildren. This is a nation vanishing before our eyes, in the space of a single human lifespan.

Similarly, every 100 Taiwanese can expect 19 grandchildren between them4; every 100 Puerto Ricans 22 grandchildren and every 100 Italians just 36 grandchildren. This is not a ‘white’ problem, a ‘Western’ problem, or a ‘developed country’ problem - this is a whole world problem. Thailand is a nation where GDP / capita is just $7,300, and yet every 100 Thai can expect just 37 grandchildren - only a fraction more than Italy. There are many countries that will get old before they get rich.5

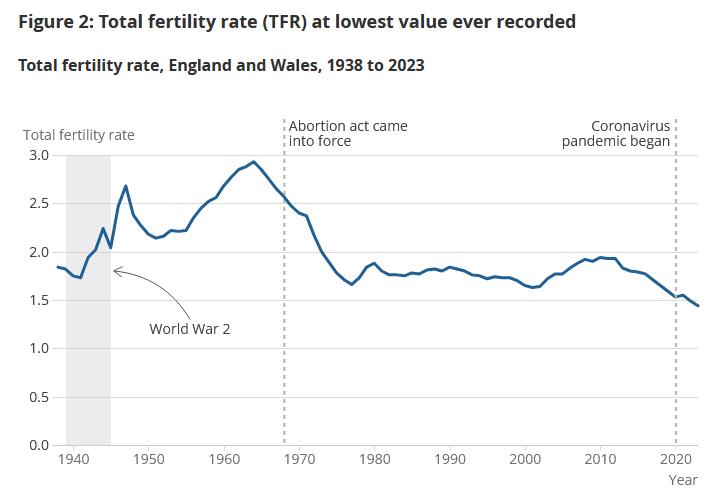

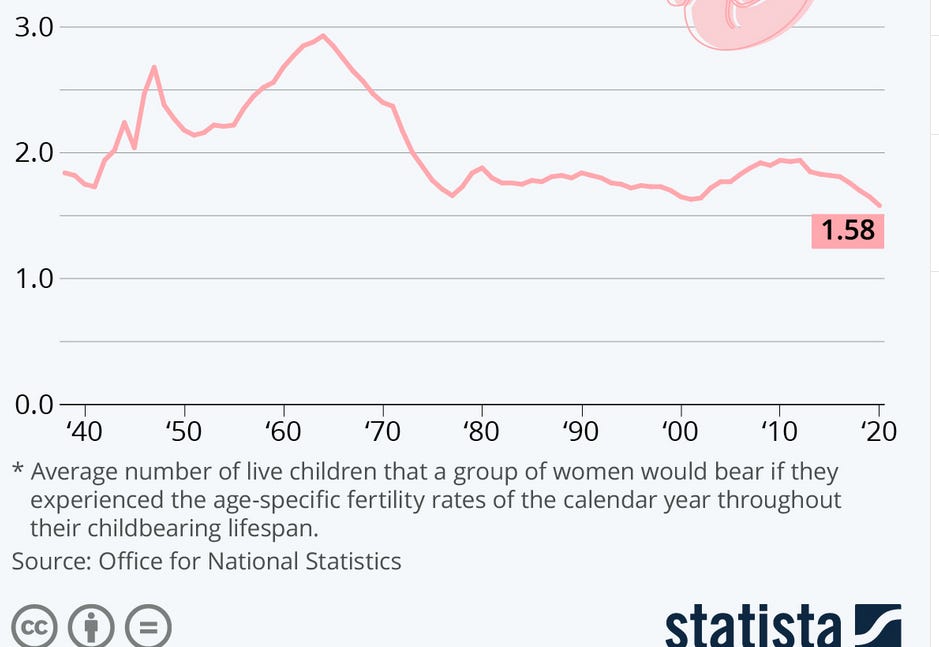

In England and Wales, TFR fluctuated between 1.6 and 2.0 from the 1970s onwards, but in the last ten years has been plummeting, most recently hitting 1.44 - the lowest on record - a number which means that every hundred Britons today can expect to have just 52 grandchildren. A decade ago these rates would have put us amongst the lowest in the world; now it is practically mid-table.6

The Little Golden Age

I came of age7 in the ‘Little Golden Age’ (1992 - 2008)8, at the ‘end of history, a period where one could be confident things were getting better: economically, socially and geopolitically.

The economy was growing and household incomes were rising. Budget airlines transformed travel to Europe and eating out become far more affordable. Eastern Europe was integrating into the world and Russia seemed like it might be next. China was lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and the standard view was that growing prosperity would force it to liberalise and democratise.

Science was advancing and the forces of religion and superstition falling back before it. We laughed at the Victorians for their supposed sensitivity on covering up table legs and Bowdler for censoring Shakespeare. We were - obviously - on the side of Salman Rushdie, of Lady Chatterly’s Lover and of Life of Brian.

A mark of the times was that people frequently complained that the main political parties were ‘too similar’ to each other.9 Tony Blair, for all his faults, was both capable and popular. Society was liberalising on issues of race and homosexuality, and while of course there were arguments about how far and how fast, they rarely seemed to leave deep or lasting divisions.

Of course, the Dot Com crisis, 9/11 and the War on Terror were a major blip - but life rapidly got back on track. Millions marched against Iraq - but the concerns were ethical, not existential: it was a war of choice that never threatened our own quality of life.10 There was nothing in the period that had the direct impact on most people’s lives that the COVID-19 pandemic or the financial crisis did.

With hindsight, we can see that many of the seeds of our future problems were sown in this period, whether the overly lax regulation of the banks, or the constitutional settlements that have hamstrung future governments.11 Is it not thus in any Golden Age?12 But at the time, life felt good, and we knew it.

The revolution that ate itself13

In the Little Golden Age, both social and economic liberalism appeared to have won the argument hands-down. Individual liberty had won - why shouldn’t people live as they wished, love who they wished and do as they wish? Fuddy-duddies might object, but they did so pointing to millennia-old books, or making unconvincing arguments about eudaimonia. Hedonism might be in some ways shallow, but it was delivering what it had promised: a better, happier, more optimistic life.

Today, this is much less obviously true. Society has become unmoored from its foundations, with radical movements and conspiracy theories proliferating on both left and right.14 The left has retained the strength of its compassion, but large;y abandoned broader Enlightenment principles. What was once steadfast support for science has become replaced by ‘your truth’, ‘lived experience’, culminating in the Orwellian position that the state would announce that a man was a woman, and you would have to believe it. Support for free speech has given way to support for censorship in the name of ‘preventing emotional harm’. And equality and race-blindness have fallen before the new tenets of ‘antiracism’ and critical race theory which argues, in the words of Ibram X Kendi, “The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination.”

The right has also failed to cover itself in glory. Partygate and the Truss minibudget were, deservedly bodyblows for the right’s credibly, and across the Pond, even those who support Trump can hardly pretend he is a paragon of conservative virtue. Too much of right has spent money like water, unquestioningly accepted progressive frameworks (both legal and moral) and failed to recognise that words and hyperbole must be followed by actions. A disturbingly high minority are openly flirting with racism, including by advancing the peculiar and unpleasant view - shared by fewer than one in seven of the UK population - that you have to be white to be English or British.

But it is the modern progressive positions that have become mainstream across almost all of our public institutions, the large NGOs and significant parts of the larger corporate sector. It is they that are taught in schools and enforced by HR departments. Much of this was done in the name of the Public Sector Equality Duty which requires public institutions to, “foster good relations between people who share protected characteristics [like race, or sex] and those who don't.” Based on the results - a society increasingly polarised on political, identity and cultural matters - by focusing on what divides rather than what unites us, our institutions have done the complete opposite of what they intended.15

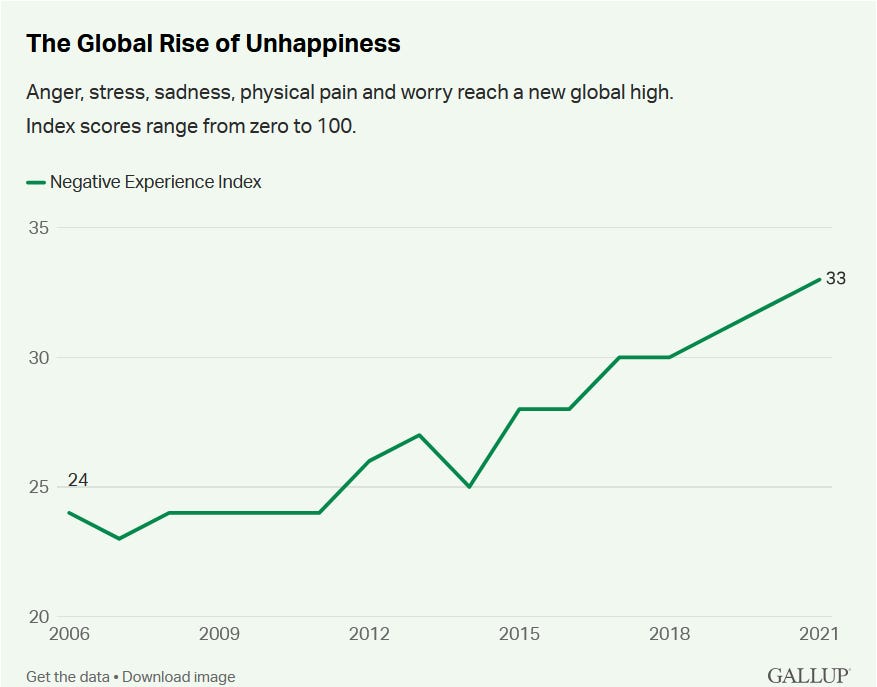

But even more importantly, progressivism is failing on its own terms. If the modern, progressive, liberal movement from the ‘60s onwards is for anything, it is surely for making people happier, freer and more fulfilled, able to live their own lives as they wish and express their identity free from oppression.

For about half a century it appeared to be achieving this. But modern society is no longer making people happy, more connected or more fulfilled.16

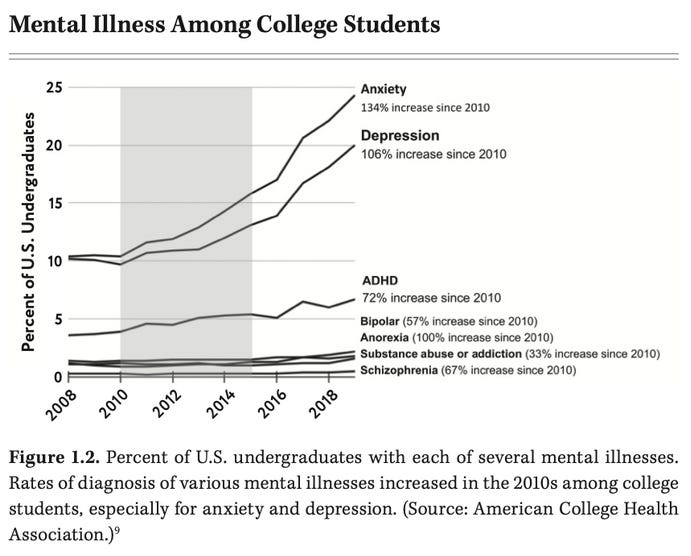

I’ve written before about the rising levels of mental unhealth amongst young people, well-documented by Haidt and others

Loneliness is on the rise - as it has been now for decades - and, repeated studies, whether on numbers of friends, or how often people socialise show the same trends.

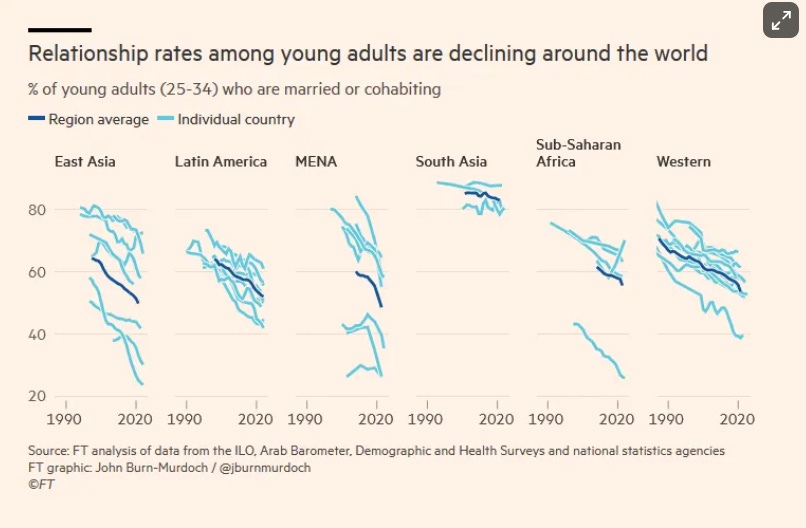

In a 2023 poll from the Survey Center on American Life, 56 percent of Gen Z adults said they’d been in a romantic relationship at any point in their teen years, compared with 76 percent of Gen Xers and 78 percent of Baby Boomers. And the General Social Survey, a long-running poll of about 3,000 Americans, found in 2021 that 54 percent of participants ages 18 to 34 reported not having a “steady” partner; in 2004, only 33 percent said the same.

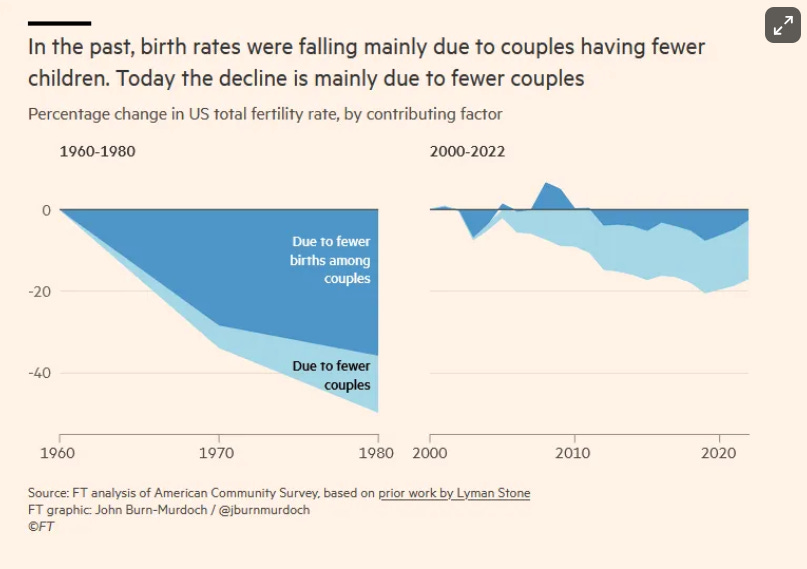

And young people are not just getting married or forming relationships later, they are having less sex. Whether or not you agree that it was a good thing that progressivism enabled people to ‘throw off the shackles of marriage’ in favour of ‘free love’, at least in the 20th century it did actually deliver the free love . The progressive society of the 2020s brings with it neither marriage, relationships nor sex - nor, of course, children:

Back to birth rates

There is always a danger that those suggesting how to increase the birthrate simply push the political agenda they had already. Make houses cheaper! More parental leave! More free childcare! Smash patriarchy! Stop women working! Abolish capitalism! Less regulation!

In some cases, these are worth doing anyway: it would be great if houses were more affordable and rents fell, whether or not it leads to more babies. But even if it may help on the margins, we should be cautious about believing that our own pet political project will save the day - simply because in every case there are so many counter-examples.17 As demographer Paul Morland documents in ‘No One Left’, birthrates are falling rapidly in countries with generous childcare and parental leave (Scandinavia), cheaper houses (parts of Europe, Latin America) and more traditional societies (Japan, South Korea). The few counter-examples - such as Israel - are highly sui generis and do not have lessons that can easily be adopted by other countries.

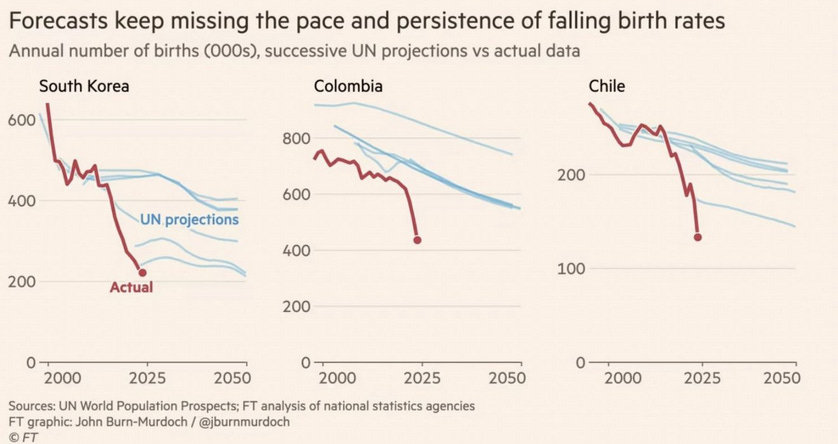

People rightly caution that demography is an area where long-term forecasting has a poor history, and that interventions can do more harm than good. Half a century ago, Western environmentalists such as Paul Ehrlich were enthusiastically cheering on as India forcibly sterilised its own population. Maybe in fifty years’ time, artificial wombs and robot nannies will have made our current concerns seem quaint.

We should certainly take care that our urge to fix this challenge does not lead us to embrace inhumane, cruel or unjust ‘solutions’. But ‘eh, it might fix itself’ seems also overly complacent.18 Birthrates are not just falling - but falling faster and further than predicted, even a few years ago.

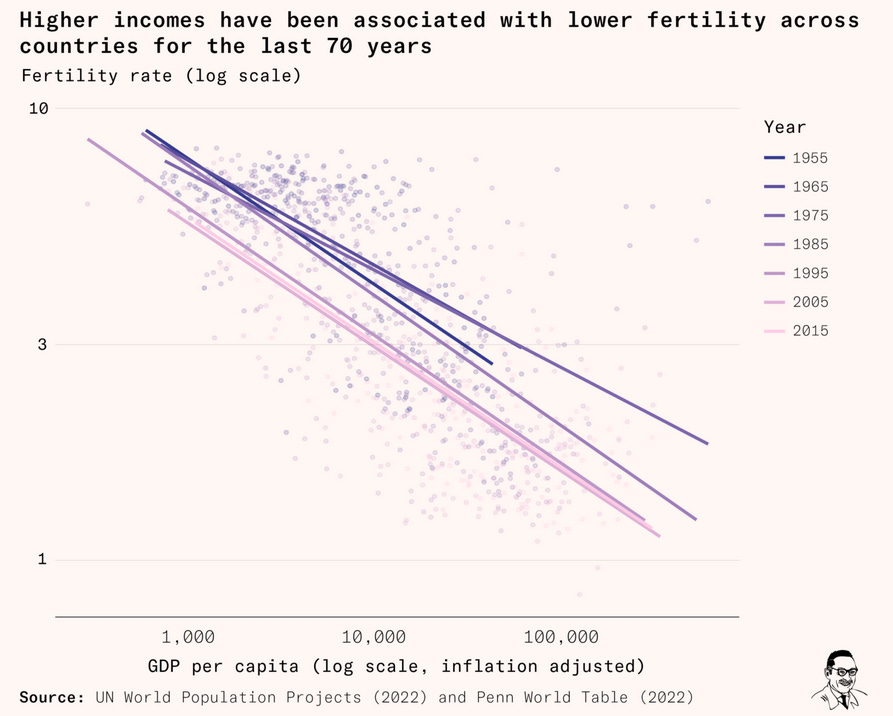

We face a global problem, so should look for global causes. What if the Great Filter is not nuclear weapons or nano-technology, but economic prosperity and birth control? Now, that would be depressing. But there is good evidence that - far from the problem being expensive housing or childcare - that as societies get richer, they have fewer children.

This perspective, from Cartoons Hate Her, is also compelling:

The majority of the fertility crisis can be boiled down to higher expectations—not only financial expectations. Expectations of the type of parent you want to be, expectations for how safe and comfortable you want your kids to be, and the biggest obstacle of all: expectations for who you want to marry.

Still, we can take some comfort that this decline is not monotonic. If we zoom in on the England and Wales chart, we can see clearly that twice, birthrates increased again - in the Baby Boom, and following the Little Golden Age. That second little bump may seem small, but actually results in TFR going up to 1.98 - nigh on replacement rate.

And, similarly, we can see that the current global free-fall of the last ten years aligns suspiciously well with the widespread adoption of the smart-phone and social media. Is AI going to kill us all not by turning us into paperclips, but by distracting us with artificial companions that mean we don’t want to procreate? More prosaically, if social media is making us more depressed, less willing to go out, less extroverted and more neurotic, it is hardly surprising if this also shows up in falling birthrates.

It’s all about culture

If we look today at groups who are having more children, it’s all about culture. I don’t just mean the Amish and the Haredi: Christians or Jewish families in faith communities that value children, or people who come from a tradition of larger families (3+) who continue to do so.

In a richer society, people have more choices. We will never be able to make having children an option which involves having more money, more time, or more choices than not doing so.19 One can look at in terms of Baumol’s cost disease, or what the ‘next best alternative’ is. Childlessness begets childlessness, and when your friends are not having children, there is a much higher social cost to doing so yourself.

People will only start having the children if we change the culture so that more people want to - and so that it is normal to do so. By changing the culture, I don’t mean trying to recreate some mythical 1950s or Victorian or 18th century society: technology cannot be put back in the bottle, nor should we wish it to be.20 Societal change rarely goes straight backwards - but can find new equilibria.

This will surely need to involve a society actively valuing families and children more than we do now. Some of the ‘tangible’ policies discussed earlier - cheaper housing, better parental leave, abolishing the two-child benefit cap - may help here less in their material benefits, than in the wider signal we send. Without wanting this to be another post All About the Phones, it may involve taking some action here.21 And just as films and TV shows normalised gay relationships in the ‘90s and ‘00s, this would need to be reflected in wider societal media, television and films. We will need to become less demanding in terms of regulation, oversight and parental expectations - a societal and cultural change as much as a government one.

This is a post long on problems and short on solutions. I don’t know what this societal change will be. However, I suspect it will need to involve Government and wider society moving in harmony on it, rather than fighting each other - or one part sitting it out.22 It is likely to involve choosing the best elements of the old, and partnering it with things that work from the new. It also, to me, seems likely that different elements of society will take different paths; a variety of solutions rather than one single way forward.

What does seem likely is that societies, cultures and sub-cultures who solve this problem will continue - and those who don’t, won’t. On current trends, South Korea and Japan will effectively cease to exist as viable countries within the century.23 For us in England, like the elves we have a little longer to linger and fade, at least for now24 - though based on the last decade’s fall in TFR, we should not count on that to last.

But solve it we must, as humanity, or much that was fair and wonderful shall pass for ever out of Middle-earth.

As is sometimes the case in science-fiction, such as the Asgard in SG-1 who have been cloning themselves for so long the process is starting to break down.

The opening quote, about Gondor, and specifically about the kings of Gondor, is perhaps not the best, as it is not humanity that is failing, only Gondor and, particularly, its ruling class.

And not due to any obvious reason, such as the repeated waves of plague that halved the population of England in the 14th century.

All statistics taken from Our World in Data.

Note that even India is now sub-replacement fertility at 1.98 and falling - though given its young population, it’s population is forecast to continue increasing for some time.

Anyone who thinks immigration is a long-term solution should have a glance at the map above and remind themselves that (a) immigrants rapidly converge to the domestic birthrate; and (b) in a decade or two there will be very few high birthrate countries left. Even in Africa, the one continent with above replacement fertility, birthrates are falling fast in most countries.

To be specific, I was 9 at the beginning and 25 at the end, meaning my entire teenage, student and early career years were spent in it.

In Britain. Globally, one should clearly start it in 1989, but in the UK, starting before Black Wednesday would be a bit peculiar.

As the Archangel Uriel puts it in Scott Alexander’s Unsong (published and set in 2016, or 8 years after the Little Golden Age had ended, and reflecting a ‘new normal’): “USER FFUKUYAMA COMPLAINS THAT THE POLITICAL SYSTEM HAS BECOME BORING. IN ORDER TO MAKE THINGS MORE INTERESTING, FIRST WORLD COUNTRIES WILL OCCASIONALLY FLIRT WITH FAR-RIGHT NATIONALISM.”

Compared to, for example, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the subsequent energy price spike and the taking in several hundred thousand Ukrainian refugees, all of which touched people’s lives much more directly.

To choose a less predictable example than I might, the Aarhus Convention, signed in 1998 and ratified in 2005, is a major reason why we find it so difficult to build reservoirs, renewables, nuclear power and transport infrastructure, by turbo-charging the ease at which judicial reviews can be granted against major infrastructure. This not only harms the economy directly and makes our infrastructure projects some of the slowest most expensive in the world, the secondary effects of very expensive energy and poorly connected towns and cities also harm growth and productivity.

Well, not always - sometimes they are ended due to external pressures. But quite often it is.

I appreciate that this does not greatly distinguish this revolution from most other revolutions.

Though not myself a believer, I have much sympathy for Tom Holland’s thesis that our society is deeply rooted - even when we don’t realise it - in Christian values, and suspect that in the ‘80s - ‘00s, despite public attendance at religious worship having dropped dramatically, there was still a level of implicit assumptions there that were having an important stabilising impact on liberal progressivism. And that as these stabilising assumptions have faded, our society has become increasingly unmoored, and subject to buffeting by the latest ideological fashions. As Chesterton said, ‘When men choose not to believe in God, they do not thereafter believe in nothing, they then become capable of believing in anything.’ Universal Human Rights was a clear attempt to provide an alternative anchor, but it is not clear it can provide the same level of stability and mooring without becoming a parody of itself.

Most of the Equality Act 2010 is good, sensible and necessary. It is Section 11 - containing both the Public Sector Equality Duty and the provisions on so-called ‘positive action’ which enable ‘no-whites’ internships and similar - which causes almost all the problems, and should be repealed.

Some of the charts below are from the US rather than the UK. The trends on these are very similar in both countries.

I would perhaps argue that, at most, in some countries certain factors may have become so bad they are now limiting factors - with housing perhaps in this state in the UK. But in most cases these will only help at the margins, and will not in itself solve the issue.

A world in which birthrates collapse almost everywhere and global society is replaced by groups such as the Haredi and the Amish is also pretty dystopian when one thinks of the scale of the societal crash that would be needed for this to happen, given the relative size of the two groups. Sure, it beats ‘humanity becoming extinct’ but it’s hardly the ideal option.

The Easterlin Hypothesis for the Baby Boom - that people have more children if there living standards are higher than what they expected them to be - may offer a little help, ‘living standards always rise faster than we expect them to’ is hardly something to count on.

Japan and South Korea - and Iran! - also show that ‘more traditional family and gender roles’ doesn’t necessarily translate into ‘higher birthrates’.

I increasingly think we may end up seeing mass use of smart phones and/or social media as one of those big societal mistakes, such as smoking or CFCs or lead in petrol. It will be considerably harder to reverse than the latter two - but it may be unavoidable.

Some people are Very Certain that governments can’t do anything at all to change how people think about families, or marriage, or children. These people seem to ignore that, for example, changing attitudes on race were achieved in part by these messages being taught in schools, promoted by public bodies - and by laws outlawing racial discrimination. It certainly wasn’t all government - but government played its part.

We can debate what level of immigration is compatible with integration and cultural preservation, but immigration at a scale where 85% of the country is new within two generations would seem to exceed any reasonable boundary.

Losing 50% every two generations is very different from losing 85%.

Thanks for writing this (or I guess, thanks to the paid subscribers!). One of the most significant problems facing humanity today, and under discussed and under appreciated.

Footnote 14 ends mid sentence (and thought)

glory.Partygate is either looking for a space or a .com at the end.

"Much of this was done in the name of the Public Sector Equality Duty [which] requires public institutions to "

"Based on the results - a society increasingly polarised [on] political, identity and cultural matters"

"with housing perhaps in this case in the UK" should lose the first in, or swap case for state.

"We should certainly take care [something is missing here] does not lead us to embrace"

I don't understand why schizophrenia rates are up 67% in the chart you share. I thought schizophrenia was very genetic, and should be very stable? I admit this isn't very relevant to your hypothesis, other than throwing doubt on the veracity of the chart.

"This is a post long on problems and short on solutions".

Thank you for having the modesty not to suggest solutions. I wish more people did.

Often pointing out the issue in itself leads to mitigations while many proposed solutions (Marx etc) disastrous.

I wondered how successful a society would be where you can self select to either point out problems or to suggest a solution. Then i remembered we call them "The loyal Opposition" and "The government" and its been going quite well for longer than most other societies.