Thoughts in Brief: AI, the New Victorians and Fettering Discretion

An occasional series for shorter thoughts

A number of people have asked me about when I’ll be posting the Wisdom of Crowds results from the forecasting contest. I’ve been holding off because Will Hazell at the i paper very kindly agreed to write it up, but unfortunately the piece got pushed back due to a series of clearly much less important events such as the Epstein files, Keir Starmer nearly being forced out, and other such trivial matters.1

However, it is now out, a great piece by Will Hazell, which you can read here, including some forecasts from (and a lovely profile of) last year’s winner. I’ll put up the full Wisdom of Crowd forecasts (and my own) some time in the next few days.

Human Labour as a Premium Service

I regularly come across the sentiment from professionals in a field that AI won’t be useful because it can’t do the job as well as they can. You hear this a lot now from translators and interpreters - one of the fields which AI is disrupting fastest - but it will no doubt come for other professions faster than we realise.

I’m sure they were right about all the ways that AI still made mistakes and was less good at translating than they were.2 But in the assertions that no-one could rely on it, they were losing sight of the fact that hundreds of millions of people are already using AI in this way - whether that’s to read a foreign newspaper article, or to translate when conversing in a shop abroad, or with a tourist asking directions.

The history of human progress has largely involved developing products that were a little bit worse, but a lot cheaper.3 Factory-produced clothing is less good than a tailored suit - but the Industrial Revolution brought cheap clothes to the masses. Flying EasyJet is a less pleasant experience than air travel in the 1960s - but a whole lot cheaper. Attending a live concert is better than a recording - but recorded music is ubiquitous in our lives.

AI will be no different.4

Rather than arguing that AI can’t provide what they’re doing, service providers would be better arguing that they still provide a premium service. AI translation may be good enough for that newspaper article - but not for the soul-searing novel. A human artist may be able to draw out someone’s real desires, producing a picture the AI would never have thought of. In some areas, such as teaching, the need for humans is more obvious: no AI, however capable, can ever replicate the physical presence of a human teacher in the classroom.5

That doesn’t mean there won’t be disruption. The Industrial Revolution resulted in a lot fewer people employed as tailors - but tailors do still exist, even today, and the total amount of clothing we use has dramatically increased. The advent of music streaming saw bands and musicians shift to making more of their money from concerts and touring, but professional bands and musicians still exist.

AI will make translation, art, and many other things available in places where it was never previously commercially viable. Though it may be a bumpy ride, that abundance is intrinsically a good thing: how many of us would wish to reverse the Industrial Revolution?6

But for those in the services disrupted - and let us be honest, that will be many of us, one way or another - rather than denying that the tide is coming in, it is likely to be more productive to think about how we, as humans, can still provide a premium service.

The New Victorians

We have a shared mental model of the Mediaeval period. It involves castles, knights, peasants, longbows, monks, witches, the Crusades and the Black Death, amongst other things. It draws on legends of King Arthur and Robin Hood, and countless book, television and film depictions, as well as real life.

It may not be perfectly historically accurate, but we all know where we are when we see it depicted - or if we see a fantasy setting that is clearly drawn from it, such as Game of Thrones, or Miles Cameron’s The Red Knight series.

The Wild West is perhaps another period which has a distinctive ‘shared cultural image’, heavily based on but not always entirely faithful to the historical reality.

As the Victorian period fades fully beyond living memory,7 it feels that in recent years we have been creating our own, new, shared cultural image of the period, reimagined for modern sensitivities. It can be found in media products such as the Enola Holmes films and Hogwarts Legacy, in books such as Pullman’s The Ruby in the Smoke, or in slightly more fantastical depictions, such as the recent Wonka film, Marie Brennan’s A Natural History of Dragons, or more dark and sinister variants, such as in the computer game Sunless Sea.8

Just as our Mediaeval image has knights, peasants and castles, so our ‘New Victorian’ is populated by orphans, workhouses and factories, by industrialists in top hats, feisty young women and factories. Explorers, scientists and high society join the working classes and underworld as they creep through London’s smog. It is a time of wonder and exploration, of great wealth and of poverty, of social conflict and technological change.

So far, so true. Just as our shared Mediaeval image is largely accurate, so too are the new Victorians firmly rooted in reality, even if the elements that come to the fore owe as much to Dickens as to a history textbook. But there are also some differences.

For one, it is surprisingly multicultural - though in quite a subtle way. Thanks to the Empire, it was absolutely possible to encounter a Sikh traveller, a Chinese businessman or a freed African slave in Victorian London. Wealthy Indian children attended England’s top private schools and the first Indian MP, Dadabhai Naoroji, was elected to Parliament in 1892, for Finsbury. It is rare that any individual character in a new Victorian setting is implausible - yet the proportion is typically closer to that of 21st century Britain, rather than the very small minority that existed in practice.9

Perhaps more significantly, social attitudes are surprisingly modern. Racism and sexism exist, but it is often depicted more along the lines of the 1980s - attitudes held by a few unpleasant people, rather than the deeply embedded social norms that defined society, and would have been believed at a core level by most people. Notably, when a protagonist defies these social norms, any character who is not a villain rapidly comes round to the idea, with their previous attitudes being discarded as a bit of fuddy-duddy stuffiness, rather than anything they really believed.10 Needless to say, this is not how deeply embedded societal mores actually work: most people really do believe in what their society tells them is true.11

Science and technology can be subtly different, too. The Victorian period covered almost seventy years, and sometimes elements from later years are found surprisingly early (or have diffused rather more quickly than they did). As wizards are to the Middle Ages, so steampunk is to the Victorian era, with sometimes even primarily conventional settings having the occasional steam-punk element in the laboratory of a wild-eyed tinkerer.

Overall, this seems like a positive development for fiction. The Victorian period was a pretty incredible time, of great changes and tremendous energy, for both good and ill, so I’m glad that modern story tellers want to set stories there, and have found a way to do so that appeals to a 21st century audience. Just so long as, as with the ‘Mediaeval’ settings, we remember that it’s not always identical to reality.

Limited Trust Fetters Discretion

A couple of months ago I came across a remarkably terrible idea, which was that all (US) academics should be forced to disclose their SAT scores - with, presumably, those falling below a certain line being dismissed or demoted.

It is not hard to find problems with this idea.12 Outside pure maths and perhaps a couple of other subjects, raw intelligence is hardly the only important measure of whether someone is a good academic.13 For people who could be in their 30s, 40s and 50s, isn’t there a more recent measure of achievement that could be used? The list goes on.

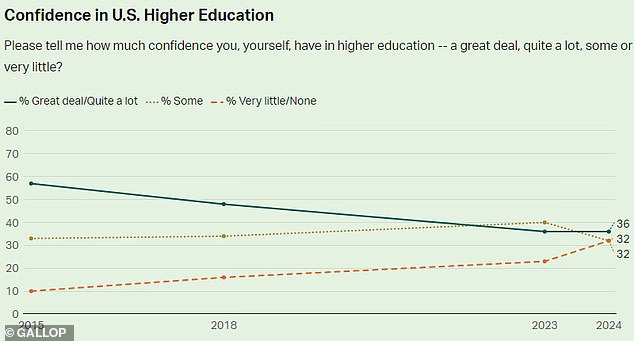

But it’s worth understanding where even dumb ideas come from. This arose in a context in which a large proportion of the US public have lost faith in universities and, particularly on the right, there is real scepticism as to whether academics are even interested in valuing academic prowess or meritocracy - and whether the peer review process for grants and papers is measuring anything other than political conformity.

I say this not to defend this particular idea. But to make the point that, in other areas where we don’t trust decision-makers, we regularly fetter decision-makers’ discretion in a way that predictably leads to sub-optimal decisions - because we believe the alternative is worse.

One area of this is public procurement. We worry that if we allow ministers to award contracts to whoever they consider best, they will give them to cronies or political donors. So instead we create rigid procurement frameworks, where bids are ‘scored’ against certain criteria and the highest scorer is awarded the contract.14

Unsurprisingly, this often produces bad results. One example that happened while I was in Government involved the National Tutoring Programme, designed to help children catch-up after the school closures during COVID. The highest scoring company was Randstad, a company with minimal prior experience in this area - and, although the minister responsible badly wanted to award it to another bidder, he was told that, if he did, the Government would be successfully sued. Cancelling the whole tender and restarting would have taken months - with no guarantee of a different result. So Randstad was awarded the contract and, predictably enough, they fell massively behind target and were ultimately axed.

Large employers are often worried that managers will be nepotistic, or discriminate.15 So instead of just saying ‘hire the best person’, they develop rigid hiring and promotion frameworks, where the same questions have to be asked to every candidate, and candidates scored against certain ‘competencies’, with the highest scoring candidate appointed.16 All of which increases fairness (or at least the odds of proving fairness in court), while reducing the ability to actually hire the best person.

Now, we should be clear that ‘politicians might award contracts to cronies’ or ‘managers might discriminate’ are not strawmen: they are things that actually happen and we are right to guard against! But we should equally be clear that, in a world where we had perfect trust in politicians to award the contract to the best bidder, and managers to always hire the best person, we wouldn’t have any of these systems. Fettering discretion may be a necessary evil, but it is only a good thing in as far as it prevents even worse outcomes.17

One of the things which I go back and forth on is whether we should introduce background-blind admissions to universities - in which applicants are judged solely on their A-Level grades/internal tests/portfolios. To the extent that universities are genuinely trying to find the best candidates - which I’m sure some still are, particularly at some Oxbridge colleges where the tutors making the admissions decisions are then directly teaching those students - it would make the results worse.18 But to the extent that universities are pursuing social engineering goals and ‘equity’,19 aiming to meet pre-prescribed ‘targets’ on background or ethnicity, and massively dropping entry and final degree standards, it would make things better.20

The most discretion, and the best outcomes, occur when there is a common understanding of what the goals should be, and all parties can have confidence the decision-makers will genuinely pursue those goals. In such scenarios, more information and maximum discretion is always desirable.

But as goals become misaligned, and distrust grows, the clamour to fetter discretion intensifies - not because it is seen as ideal, but because it is recognised the only way to avoid even worse outcomes. And such a low trust world ends up with worse outcomes for everyone.

Shocking, I know.

And let’s ignore for now whether they’ll still be right in one year’s time - or five years’.

OK, it has occasionally also involved developing better products.

There may be important ways in which it is different. But at a minimum it will be like this.

Maybe a sufficiently advanced robot could - but we are still some way off that!

There obviously could also be very negative outcomes from AI, as outlined in the recent essay by Dario Amodei - not to mention the more doomsday scenarios.

I don’t recall ever meeting a Victorian, but I must have done: anyone 87 years or older when I was five would have been born in the Victorian era, and people in their early 90s would have even remembered her. And of course the big twist in Tom’s Midnight Garden is that Hatty is really Mrs Bartholomew, a little Victorian.

A game ‘in which Victorian-era London has been moved beneath the Earth's surface to the edge of the Unterzee, a vast underground ocean.’

One could make the same observation about the proportion of young women who are feisty and adventurous feminists.

A friend pointed out that Will’s ‘coming out’ scene in Stranger Things suffers from a similar problem: many people in the ‘80s wholeheartedly believed that being gay was wrong, and the idea that a dozen or more people would unequivocally accept him belongs more to the 2010s than the 1980s. His brother quietly indicating he’d stick by him, regardless - as occurred in Season 4 - is plausible; universal acceptance less so. The depiction of Robin - who lets out her secret carefully, cautiously and only to people she is sure she can trust - is much more realistic.

We currently live in an unusually diverse society, which explicitly holds up diversity as a core value, and in a media and information landscape which is unusually fractured, so it can be hard to remember how much stronger social norms were in the past. But still, just consider some things that we do almost all agree are bad (say, two 14 year olds having an arranged marriage - normal through much of history) and think how people would react if someone told you they were doing it. This isn’t an ‘all morals are equally valid’ argument, but it is arguing that people in the past genuinely believed in their social mores too!

Including, for example, what about academics who didn’t attend high school in the US and so never did the SAT? Or that using a graduate test, such as the GRE or GMAT, might be more appropriate for measuring people who have PhDs, than the SAT?

And even in maths, there are important differences between acing the SAT and the skills that one needs to be a good researcher.

In some countries and at some times, they don’t even trust government to score against multiple criteria, but insist the contract must be awarded to the highest bidder.

Or, at least, they want to be able to prove to the courts in the case of a grievance that their managers did not discriminate.

If the employer is the civil service, they may do even more moronic things, like forbidding managers from seeing the performance ratings or assessments of internal candidates, in case of unconscious bias, because obviously unconscious bias manifests more when assessing someone’s work over a year rather than in a 40 minute interview, and knowing whether an internal candidate is ranked ‘improvement needed’ could have no bearing on deciding whether or not to promote them.

I personally think that we have gone to far in both procurement and hiring, and we could have meaningful checks on corruption/nepotism/discrimination that were almost as good while restoring a great deal of much-needed discretion. But that is another post.

It is true that a kid who self-taught themselves calculus and stormed to straight A*s after a troubled childhood in a troubled school is likely to be stronger than one who had every advantage.

Or trying to get bums on seats.

This is also another post.