Sanctuary or Struggle?

What do BlueSky and the University of Austin have in common?

In 2017, American Christian Rod Dreher wrote a best-selling book called The Benedict Option. It argued that mainstream American life had become so culturally detached - indeed, inimical to - Christianity that Christians should prepare to much more systematically opt-out of wider society, taking greater responsibility for building their communities, friendships, schooling and more around and within the Church.1

This, naturally, provoked a good deal of debate, including about whether Dreher was right about the state of society and, if he was, whether the Benedict Option was the appropriate response. But of course, the Benedict Option is nothing new. Some religious - and other - communities have been doing it for years, with the Amish2 and the Haredi Jews being amongst the most well known.

But Benedict Options are not only found amongst the religious. When a group of academics, disgruntled with the state of elite universities in prioritising identity politics, affirmative action and ‘emotional safety’, decided to establish the University of Austin, Texas3 as a haven for those who favoured meritocracy and free speech - that is a Benedict Option. And when a bunch of left-wing commentators, academics and others become fed up with Twitter’s algorithmic deterioration and tolerance of abuse decide to instead join BlueSky - that is also a Benedict Option.4

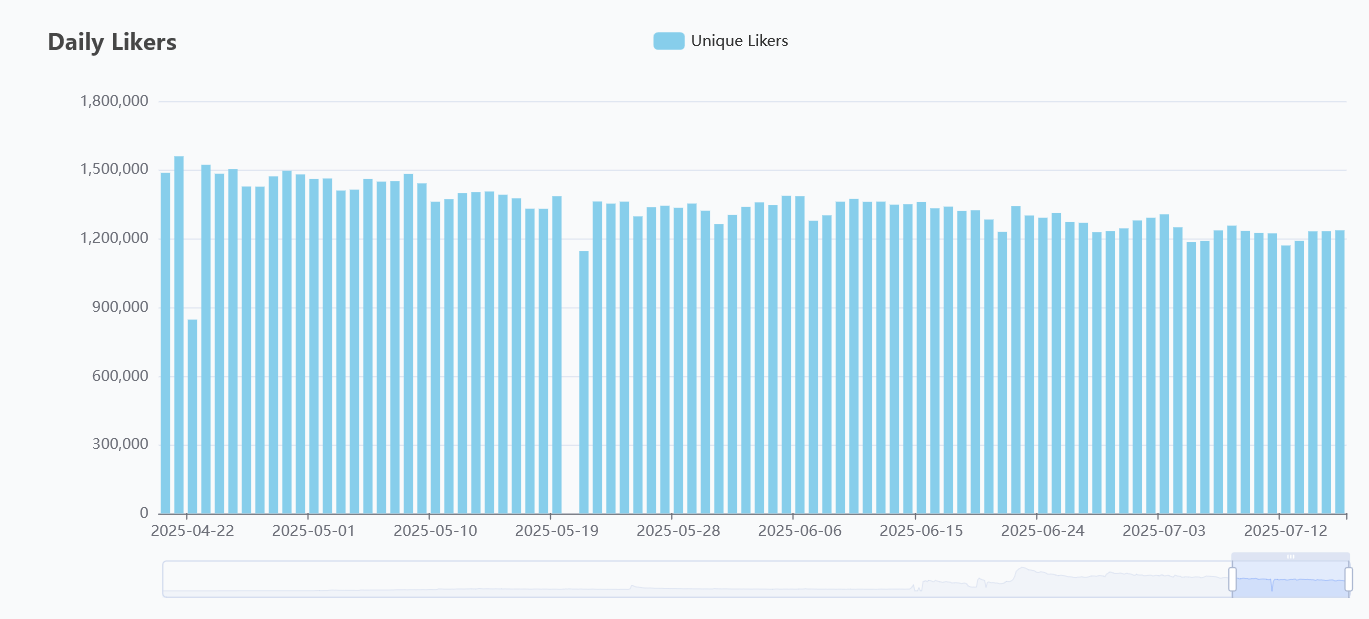

So what’s the temptation of the Benedict Option (in the broader sense)? Initially, in some cases, the founders may hope that their new foundation will become the dominant model - that Twitter will wither and die, or that the University of Austin will outshine Harvard as a beacon of scholarship. But even once that appears unlikely (BlueSky has 20 - 50 times fewer users than Twitter and on most metrics such as ‘daily likes’ seems to be on a slow decline;56 the University of Buckingham - the UK’s 1980s answer to Austin - has not eclipsed Oxbridge) - many people continue to see value in Benedicting.

Are they right? And what are the drawbacks they may be overlooking?

Firstly, and most simply, Benedicting provides a sanctuary for those who just want to go about their business. The family of faith who wants to bring up their children in the way they believe is right; the pure mathematician who is tired of having to make land acknowledgements or ‘consider diversity’ when recruiting; the casual social media user who wants a feed free of casual abuse and racist slurs.

There is innate value in such sanctuaries: not everyone is able, or is temperamentally suited, to take part in a contest of values. It is exhausting to always be in the company of those whose world-view you fundamentally disagree with - even if one is not attacked directly. Without such sanctuaries some would simply opt-out altogether.

Secondly, the Benedict Option can provide a place to build strong communities, to develop the younger and more experienced, and to create networks. Maybe a graduate of the University of Austin goes on to work in the Ivies, or a person posts on both Twitter and BlueSky - but finds their real community and allies on the second. Such communities and networks are of tremendous value to any movement - and in a worst-case scenario, are perhaps the only things which will allow a movement, a faith or an ideology to stay alive in the face of real oppression.

Thirdly, Benedict sanctuaries provide places where the flame can be kept alive, in exile, as with Sutcliffe’s lantern bearers, until such time society is ready to receive it once more. Work can be done here, new ideas developed, new concepts awoken, strength girded, until one day, like Turgon opening the league of Gondolin, they can usher forth, unsummoned and unlooked for, with bright mail and long swords and spears like a forest, to bring the wisdom of phonics to a benighted nation.7

Again, there is merit to this, particularly if one is talking of academic ideas. The truth is a powerful weapon,8 that cannot be forever denied, and individual academics can wield tremendous influence - look at E. D. Hirsch, or Kathleen Stock, or Jonathan Haidt.9 If Benedict sanctuaries can provide a place of work for such people, who might otherwise be forced out of academia, this is well done. But as a note of caution, note that most of those I mentioned worked primarily in mainstream academia, not in sanctuaries. The Noldor lost the Nirnaeth Arnoediad, and all the majesty and might of Gondolin came to naught.

But if these are the benefits, what of the costs? Again, we can identify at least three.

Firstly, just because you are not interested in the state does not mean the state is not interested in you. You may simply be trying to do your own thing, but if you are not paying attention you may wake up one morning to find the state banning kosher or halal slaughter, or home educating, or interfering in your schools. It may refuse to recognise your degree certificates, restrict access to funding or finance,10 or otherwise seek to restrict or curtail your operations. Bear in mind that in Britain today, the state will not allow you to even leave your child with someone else to look after them, and pay them for it, unless they are an officially ‘registered childminder’.11

Of course, one can ignore these restrictions, but that carries significant risk - fines, criminal records, closure - which only the most committed are willing to take. And while one could probably operate a small religious community under the radar, that is going to be harder for a university, or a social media network, or any other institution operating at scale.

The classic response to this has been to have outriders, those who champion the Benedicted community, but still involve themselves in the world to defend its existence - through advocacy, through going into politics, or via other means - as the Rangers of the North protect the Shire. Again, the classic example is from the religious world: think of a person of faith, less orthodox than those Benedicting, who will drink and network with the outsiders to help safeguard the rights of those who live a more cloistered community. But we can see it elsewhere, too. Many of the leading figures of the University of Austin also maintain roles at leading conventional universities. And there is a reason most elected politicians - who must speak to the whole nation - maintain a presence on X, even those who have also set up accounts on BlueSky.

Secondly, taking the Benedict Option hinders the ability to maintain a tolerable existence for those like-minded in the mainstream world. Maybe a Christian is not going to succeed in getting abortion banned - but they can maintain the right of conscience for nurses who do not risk to take part. Maybe universities will always be left-leaning - but they can defend academic freedom and safeguard the rights of heterodox students and scholars. Maybe Twitter will continue to have its ‘pay for visibility’ algorithms and pile-ons - but they can get the worst forms of racism and antisemitism banned. Or maybe you wake up one morning, ready to discuss what language is unacceptable on Bluesky, and find the country has elected a Reform government.

Of course, whether people are motivated to take the Benedict option often depends on the extent to which they think that contesting the mainstream in this way remains possible. Rather like Dreher on secular society, a common refrain from many on BlueSky is that Twitter is unsalvageable. It is always tempting to think this - but on the other hand, things can often get worse, and the more people of a certain viewpoint absent themselves from a domain, the easier it is to ignore or sideline their concerns - sometimes without even realising you are doing so - and the harder it remains for those who choose to remain (and note that even after taking the Benedict option, in all but the most extreme cases, typically some members of the community will continue to work in and interact with mainstream society).

This may sound as if I am advocating for people to avoid the Benedict Option and to stay in the mainstream. It is often tempting, particularly for a certain type of person,12 to think, ‘I will stay, and work within the system, and not speak out about it but ensure that I help support this cause I believe in from inside’.

I am not saying this cannot achieve anything. But there is a limit to what can be achieved here. How much did all those in public institutions who thought gender ideology had gone too far - and there must surely have been many - achieve prior to the Cass Review being published? Or what did all those in the Met who were concerned about racism manage to achieve, prior to the Macpherson report being published? Precious little, in both cases. It was, no doubt, helpful in both cases to have some ‘on the inside’ who welcomed those reviews, but they were only following, not leading.13

Again and again, I have seen people who I know detest identity politics and 'wokeness' appointed to leadership positions in public bodies and, once there, achieve next to nothing in pushing back against the zeitgeist. Typically they feel completely circumscribed in what they can do - and so achieve nothing. Nor is this unique to this topic, or indeed topics I support. I've spoken to friends who are staunch pro-Palestine advocates who say that they see the same thing there, that people who they thought believed as they did repeatedly failed to act on it when in positions of authority.

We should expect this; it is a function of the nature of modern bureaucracies: As Musa al Gharbi has written:

On the one hand, in light of her history and affiliations, it would be easy to view someone like [an Ivy League President] as endowed with extraordinary power and freedom. It would be easy to think she has wide discretion in shaping how events play out. This is true, in a sense. It is also incomplete.

The sociologist Max Weber argued that while bureaucrats do wield impressive power and social prestige, it is never truly theirs to possess. Instead, it typically derives from their office. If they are pushed out of their position or institution, their wealth and status tend to vanish precipitously too. In order to avoid this outcome, Weber argued, bureaucrats tend to avoid alienating anyone with the capacity to strip them of their rank and prestige (even to the point of compromising their integrity or alienating large swaths of the rest of society in order to ingratiate themselves to elite gatekeepers).

Bourdieu would later describe people like [this] as the “dominated faction of the dominant class.” They are elites, but their elite position is typically contingent on continued patronage from wealthy people or the state — and on association with prestigious institutions such as universities or media outlets (which, themselves, are reliant on patronage from other elites and/or the government). As a consequence, although they may fancy themselves as rebels or speakers of uncomfortable truths — and although they can and often do leverage their clout to push elites or institutions in particular directions — they also tend to know their limits, and generally take care not to cross any lines that would result in their expulsion from corridors of influence.

Of course, there are honourable exceptions. And of course, not everyone has to be engaged in struggle for a cause of a belief; there is much value in work of all sorts. But if you are telling yourself you are in the system to advance a particular cause or belief system, unless you are taking some significant risks - or perhaps writing some big cheques to those who do - it is probably best not to kid yourself about how much difference you are making.14

Thirdly, by taking the Benedict Option one gives up impact and influence. Your networks atrophy, your direct power diminishes, your following is reduced. A professor from Oxford or Harvard will always carry more clout than one from Buckingham or Austin. And in a filter bubble, you are likely to become increasingly disconnected from the mainstream, its debates, and how to engage effectively.

There is no way round this. This might matter less for a community that just wishes to create its own Eden. But for one that has impact on wider society as its goal, it is a real cost that must be faced up to and accepted.

So, should one take the Benedict Option?

I have no firm conclusion here: every situation is different. But there are trade-offs, and both taking and not taking it come with costs, which advocates of both would do well to acknowledge.

For some, those who are conflict averse, or bruised, or vulnerable, Benedict Options may have an innate appeal. But for others, who more feel the lure of status, or safety, or financial reward, it is living in the world that is the path of temptation and ease. What feels good is not the same as what is right - but perhaps there is room for both sets of talents. Even those seeking to change the world can benefit from a sanctuary for those who need rest. And even those who just wish to be left alone need their rangers.

If there is any conclusion, it is this. That those whose focus is upon creating a community where people can live (or work, or post...) as they wish, have potentially most to gain from taking the Benedict Option. And it is those who are primarily concerned with influencing and changing the wider world who give up the most.

Though sadly not in space.

Not to be confused with the University of Texas, in Austin.

Note that if the numbers leaving the mainstream option are sufficient to set up an entire comparatively sized alternate ecosystem - as with Fox News and right-wing talk radio in the US - then this is not a Benedict Option.

Though I am still on there.

Or like Irish monks rechristianising Britain, if one prefers a less fantastical example.

Though so too are lies.

Or, for balance, Judith Butler or Edward Said - as however much I disagree with them I cannot deny their influence.

Though technically speaking the Benedict Option means you shouldn’t be relying on state funding or finance.

There is, oddly, no barrier to leaving your child with anyone you like if you don’t pay them, but no doubt the state will get round to demanding to inspect that, too, in due course.

In which I would include myself.

And yes, and yet: Macpherson and Cass only achieved the impact they did by being highly respected insiders.

But the soul is still oracular; amid the market's din,

List the ominous stern whisper from the Delphic cave within,—

"They enslave their children's children who make compromise with sin."

the Musa al Gharbi insight excellent. thanks

Great post, but I'm slightly confused at your definitions (or lack thereof). Particularly footnote 4. If 80% of social media-inclined academics leave Twitter and set up a community on Bluesky, then this community is a similar size group to Academic Twitter. But you call this a Benedict Option? - this seems to contradict footnote 4.

I'm interested both in your definitions and in why you draw a distinction between small Benedicts and big Benedicts - and why you don't regard a big Benedict as a Benedict. What makes a large defection existentially different to a small defection?