Reflections on Brexit

Seven years on from the historic Brexit referendum, I reflect on what's gone well, what less well - and was it all worth it in the end?

Seven years ago today the UK voted to leave the European Union.

What followed was a whole lot of political wrangling, a near constitutional crisis and two general elections, before we ultimately left the EU on 31 January 2020 - meaning we've actually been out for less than two and a half years (and functionally out for less than a year and a half, because the 11 month transition period when nothing much changed only ended at the end of 2020).

That was then followed, as everyone knows, by a global pandemic, Russia invading Ukraine, an energy price-shock and a broader global economic crisis, none of which, to put it mildly, were what anyone was expecting.

As someone who was a strong advocate of leaving and who wrote a good deal about it, from my 2014 prize-winning essay to many pieces on my blog here in 2018 and 2019 - and who then took up a special adviser role in the government that delivered it, in the second half of 2019 - I'm quite often asked what I think about how it's going. In this post I'll be looking at why that's not quite the right question to ask, but then attempt to answer it anyway.

Not the right question

For me, and for many others, the fundamental point about Brexit was not economic success, or otherwise, but about sovereignty - who governs Britain? To put it another way, do we want Britain to continue to be an independent country, or should 1000 years of history dissolve into ever closer union? In the words I wrote in 2014:

Ultimately, whether or not the UK exits from the EU is a political, not an economic decision. A wide range of factors, in particular the ideological question over where sovereignty should reside, will be at the heart of any future referendum.

Openness not Isolation - Iain Mansfield, 2014

I would argue the same is true for a referendum on Scottish independence, or Quebec independence, or any other similar referendum. Of course, the UK was not yet as integrated within the EU as Scotland is within the UK - but already, approximately half of our laws were made in the EU, and integration was an ongoing process - driven by that commitment to 'Ever Closer Union' at the heart of the EU institutions. If the great lie of the Leave campaign was to pretend that leaving would be seamless, the great lie of Remain was to pretend that Remain was a vote for the status quo - that simply wan't an option. It is my own belief that within the next 50 years the EU will essentially resemble a fully federal Europe - with a directly elected President and shared foreign policy - but, even if that doesn't happen, further integration is almost certain.

The point of Brexit, therefore, is not whether or the Tories are currently making a hash of it or not (or, indeed, of running the country more generally). The point is that if you think they are making a hash of it, you can vote them out and put Keir Starmer and the Labour party in, and then they can actually change things - rather than having one hand tied behind their back by Brussels.

The fact that Brexiteers have allowed the question to be framed - largely by opponents of Brexit as 'has Brexit gone well?' or 'demonstrating the successes of Brexit' is a mistake. They successfully - and correctly - framed the referendum as about more than economics, but have since forgotten to do so.

You may be poised here to say that that is my perspective, but is it anyone else's? It's worth taking a look at why people voted in the Referendum.

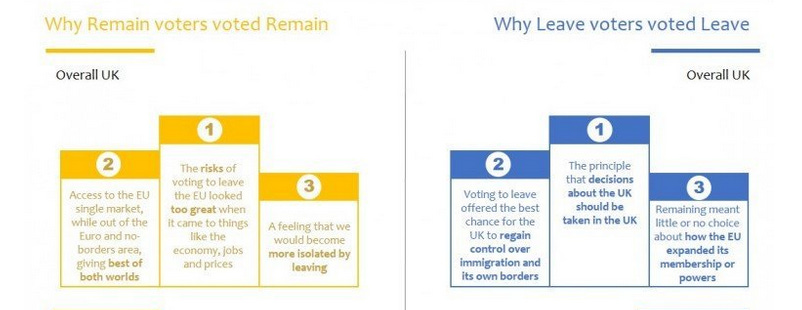

We can see that the first and third reasons why Leavers voted to leave were about sovereignty - with the second most important reason being immigration. Conversely, the first and second reasons why Remainers voted Remain were about the economy, with the third being about being isolated globally.

It wasn't that Leave voters were unaware of the economic impact - they couldn't be. The entire Remain campaign centred around the economic costs; a leaflet was sent to every household in Britain; and George Osborne announced there would need to be a 'punishment budget' with income tax raised by 2p in the pound and massive cuts to public services1. They simply prioritised other matters.

OK, whatever - but is Brexit going well?

I suppose you mean in terms of trade agreements, regulations, economic costs and so on? We'll get to that in a bit, but first let's talk about the period of turbulence.

2016-2019: The Feuding Years

I never expected we'd win the Referendum. I almost went to bed without watching the results, so sure was I we'd lose - until I saw the Sunderland result, and then couldn't tear myself away. For that matter, I never really expected to get a Brexit referendum in the first place: after Cameron's betrayal over the Lisbon Treaty, I was pretty sure we'd be in the EU for life. But having, through some miracle, not just secured but won a referendum, it never crossed my mind that MPs would try not to deliver on it.

I was far too naive. I don't want to refight old arguments here about 'it was only advisory' - it was clearly presented to and sold by both sides as the final word. The subsequent period, where large numbers of MPs openly sought to set aside the referendum result, either entirely or by demanding a second referendum, was by far the most ignominious and democracy-damaging period I've seen in my life - and I think that Britain has seen since at least the War, if not before. There were mistakes of competence made on May's side, of course, but the moral calumny was committed by those who sought to set aside the result.

Regardless of whether or not you agree with that diagnosis, there's no doubt that this period was objectively damaging for the UK as a whole. It increased polarisation - causing the rancour from the Referendum itself to set in rather than heal - and, with almost the entire government focused upon the rows, severely distracted from the day-to-day business of government. Many things that had been on positive trajectories under the Coalition (and in 2015-2016) - from welfare payments to crime to NHS performance - began to start going the wrong way. If nothing else, it exposed a significant flaw in our unwritten constitution on referenda - at least in circumstances where the result goes against the will of the majority of MPs.

Oddly enough, I don't blame the EU for this. Unlike our own MPs, they had no obligation to the British people - and every incentive to try to make the UK reverse course, both for its own case and pour encouragez les autres. In European countries, of course, if a population votes the wrong way in a referendum, they are simply told to try again until they get the right answer. It is to the immense credit of Britain, and to the underlying strength of our democracy, that this did not work here.

Ultimately, of course, the deadlock was resolved in the best possible way: by a general election in which Brexit was the central issue, delivering a new and unmistakeable mandate. But the three and a half years of wrangling was damaging and divisive - definitely not a part of Brexit that went well.

OK, so now are you going to tell us - is Brexit going well?

If we're going to look at it through that narrow lens, then - sort of? Maybe 6 out of 10? Or a B-, if we want to use grades? I'd distinguish this from the broader economic and governing performance, which is going less well.

Let's start with the good.

The trade agreement with the EU is very much close to my ideal form. A deep free trade agreement without going so far as full harmonisation or joining the customs union. I would have been willing to leave without a deal - one cannot let the polity from which one is leaving set a condition that would prevent one leaving - but it was always clear that leaving with a deal would be best. There are undoubtedly some improvements to be made on sanitary and phytosanitary issues and other technical areas, but the basic framework is good.

On other trade agreements we've also done well. We've rolled over all of our existing trade agreements - not a foregone conclusion, with many Remainers saying it wouldn't happen - and signed a few good additional ones too. This is less significant than many people make out (champions or detractors) but it does help.

We did the right thing with allowing existing EU citizens here to stay and gain settled status.

The terms of the 'divorce bill' and payments we have to make are a little steep, but well within the bounds of what is reasonable - they are, in any case, cheaper than staying in the EU would have been, and will end before long, anyway.

In terms of domestic promises, this was not a factor for me, but we are spending well over £350m a week more on the NHS than we were in 20162.

Blue passports are nice3, though obviously unimportant, and the benefits of going alone on our vaccine programme clearly saved several thousand lives.

The big positive surprise for me has been international cooperation and standing. The one Remain argument I took seriously was that Brexit would weaken our ability to stand up to and counter nations such as Russia and China. Russia's invasion of Ukraine shows this is not true: we played a key role in this and actively helped both the immediate defence and to shape the wider European response. More broadly, we seem to be playing just as strong a role before in arenas such as the G7; the new AUKUS submarine deal is excellent and the EU is terrible on China-appeasement, so no loss from being outside the EU there.

I'm pleased it hasn't led to any long term increase in support for Scottish independence, something else I was genuinely worried about.

Now for the bad.

Northern Ireland is the obvious biggy. It's the one area I didn't address in my 2014 essay that I really should have done; it also played very little part in the Referendum campaign on either side - a real area where everyone underestimated the challenges. This clearly caused significant problems and wider economic damage for several years; I am a strong fan, however, of the Windsor Framework, which has got it into a much better place for now.

On regulatory reform, other than in financial services, there has been very little done. The Retained EU Law Bill was started far too late - in 2022 rather than in 2019, as it should have been - and then tried to be rushed through on an unrealistic timetable. I support, for pragmatic reasons, the way Kemi Badenoch has taken a more limited scope for this - but more broadly, across all Government departments, there should have been a much earlier, much deeper look at regulatory reform. This issue goes beyond Brexit though: there is very little appetite to reform the regulations in our own control, which is unfortunate.

Migration is out of control. Some is due to one-off schemes such as Hong Kong and Ukraine, which have high public support; the rest is justified by the UK's tight labour market - which is all very well, but the failure to build adequate homes is pushing rent prices sky high, and pushing up house prices. The Channel crossings in particular demonstrate that we have no state capacity or will to enforce our borders. We will see if the Illegal Migration Bill works. This is the sort of thing that leaving the EU has given the government the ability to control - Parliament is now sovereign, should it choose to exercise that power - and migration was the second biggest reason why people voted Leave. It's a big reason, I suspect, why many Leavers see Brexit as not going well, for it is a visible area where we've not taken back control.

It's frustrating to still be out of Horizon - no-one on either side wanted to end science cooperation. This was a casualty of the frictions over Northern Ireland, and hopefully it can be restored.

Regarding Boris, as I've said before, I don't regret my 2019 vote. He was the only person who could break the deadlock and get Brexit done – and for all his flaws, he achieved that. More broadly, while there’s a lot I could criticise about our response to COVID, on a global level I think we did about averagely, and I’d rather have had Boris in charge than Hunt or Corbyn, the other two options in 2019. He probably got us in more trouble than we needed to with spending, but on the other hand was outstanding on Ukraine. I don’t defend Partygate at all and it was clear he had to go. I wish we’d been able to see what he’d have done without COVID – there might have been more fiscal space to deliver on the ‘tack to the economic left’ that Levelling Up and the 2019 manifesto promised, and keep the new coalition together. Or maybe it would all have collapsed in some other way. Regardless, he was the right man for the right hour in 2019.

Overall, internationally speaking (including with the EU) the shape of our exit is pretty strongly along the lines of what I hoped for in the 2014 essay, but there are domestic failures on regulatory reform and migration. With it only being a year and a half into Brexit-proper, we are still well within the 'couple of years' period in which I said we should expect to see 'some degree of market uncertainty and fluctuating economic performance' - we are seeing this, but we're also seeing a steadying outlook, driven in particular by the Windsor Framework being agreed, but also a whole variety of other technical changes being worked out.

Our wider economic performance is, of course, dire. A big cause of this is global events - the massive shock of the pandemic, followed by the Ukraine war and all that came with it - but it is true to say Britain is doing worse. I put this clearly down to our broader economic decisions.

For the last few years, we've been steadily spending more, taxing more and regulating more. Debt has shot up to 100% of GDP, inflation is setting in and debt interest payments are soaring. The response from opposition parties is invariably that we are not spending enough, and should be regulating even more. This is not a hopeful situation. As I've written before, we have an inability to build sufficiently - be that houses, reservoirs, energy infrastructure or transport - and even a massive energy price shock hasn't shaken us out of the complacency that snarls every new development in years of red tape and court cases. We've driven two-thirds of childminders out of the profession in ten years through regulation and wonder why childcare costs so much. We've cut investment in further education. And any attempt to address these issues - or to tackle the other massive drivers of state spending, such as the triple-lock, out of work benefits or uncapped university places - is met with screams of outrage or, more often, not even tried. This is the root cause of our sluggish growth and high interest rates.

Brexit isn't to blame for this. It's not to blame for Partygate, either, which is an entirely home-grown political scandal. What it does do, at least, is provide the ability for a political party to address these things - even if none of them currently are showing the will to do so.

So, no Bregrets?

Not in the sense of wishing I'd voted differently, no.

There are, of course, a number of counterfactuals that I wish had gone differently - some within our control, some outside.

I regret we exited into the teeth of a global pandemic. I regret that Cameron ordered the civil service to make no preparation for Brexit - so incredibly irresponsible. I regret that we didnt think about Northern Ireland a bit more, and that Boris was less successful as PM than as Mayor of London. I regret we never got to see a full Cameron second term, without the Coalition, and all the unfulfilled hopes of public service reform and domestic progress. And I deeply regret the three bitter years of arguments and wrangling, perhaps the most damaging part of the whole process.

In fact, if we're talking counterfactuals - and plausible ones, not ones that require magical thinking as to the EU's response - I do wonder if it would have been better for the country if Cameron had stayed on as Prime Minister and delivered a soft Brexit, staying within the Single Market. I think he could have done it - he'd have had credibility with the EU and with the Remainers in Parliament (Conservative and Labour) and, in the throes of unexpected victory, most Brexiteer MPs would have accepted it too (Cameron was, overall, very much liked and respected as a leader). It wouldn't be my preferred form of Brexit - I think there would be real downsides, in terms of being rule-takers, to our current arrangement, but it would still have been a genuine Brexit, putting us clearly outside Ever Closer Union. It would have reflected the close nature of the referendum result and - if it had avoided the three years of deadlock and polarisation - maybe it would have been worth it. I'm on the fence on this one.

Before some of my fellow Brexiteers yell at me (and to be clear, I don't love this counterfactual), it's worth remembering that if anyone had offered us this a decade ago, when Brexit was no more than a pipe dream, we'd have bitten their hand off to accept it - if not their whole arm. We have been far luckier, not just once but many times, than we could ever have dreamed of, and it would behove us to show more humility and compromise in victory.

But overall, no: I have no regrets as to the decision I made or the outcome. Brexit is a historic, generational, foundational decision, determining the future of our country at a fundamental level. Achieving it was, and is, far more important than any particular Prime Minister, which party is in power, or anything that can be read from a year or two's economic performance.

We are now, despite the bumps and the wrangling, successfully out of the EU - amd have paid a far lower price for our independence than Ireland, Israel or India and Pakistan, to name just a few examples.4 The situation is stable and the teething problems are steadily being resolved, though there is still more to do. Brexit has been achieved: what matters is that it is not reversed. Britain endures: the rest - which party is in power, whether taxes go up or down - is secondary.

Policies are more important than political parties. I firmly believe that ultimately you don't win in politics by beating your opponents, but by getting them to adopt your policies5. Margaret Thatcher famously said that Tony Blair and New Labour were her greatest achievement; similarly, New Labour have utterly, comprehensively won on issues such as the minimum wage.

Brexit is nowhere near as settled as that. The case will almost certainly have to be made again, perhaps more than once. But for now, the fact that the Labour Party, under arch-Remainer Sir Keir Starmer, is campaigning on a slogan of 'Make Brexit Work' is the biggest testimony to Brexit's success.

For now, at least, Brexit is going well.

I find the argument that Leave should have emphasised economic costs a little bizarre. In a normal election, the Conservatives tell you that Labour will need to raise taxes to afford the spending plans they are announcing and Labour tells you that the Conservatives will need to cut public services to afford the tax cuts they are promising. You boast about the good things in your plan and your opponents point out the bad things - that's how it works.

We are spending roughly an additional £40bn, or about £760m a week extra - comfortably over £350m in both cash and inflation-adjusted terms.

I know technically we could have had them in the EU, but our leaders didn't, so practically speaking, leaving delivered these.

Ireland is perhaps the best example, because they had full democratic representation at Westminster, just as we did at Brussels, but still wanted out.

Admittedly, you do sometimes have to win first to do this.