Is there really a problem with social care?

Or do people just want a free lunch?

There are, of course, many problems with social care1 - the lack of join-up between the NHS and the social care system that leads to inefficient spending, or challenges recruiting the workforce.

The most salient feature, however - the one which dominates public debates, from the Dilnot Review to May’s ‘Dementia tax’ - is the fact that it costs so much, and that people don’t want to pay. And on this point, while it is certainly true that costs have soared, it is far from obvious there is a ‘problem’ that can be solved. Rather, it is a political choice: of who pays, how and how much.

Why have costs increased?

Fundamentally, because people are living longer. Life expectancy has increased, but while healthy life expectancy has also increased, it’s done so by a lesser extent. So people are living longer with conditions such as dementia or other debilitating conditions that require care.

In addition to this, families are smaller, more geographically mobile and more likely to involve both adults working. Historically, much old age care was given in the home, by family members. But smaller families mean this is less likely to happen - particularly where people have moved across the country for work or where both adults of the next generation down are working. So a higher proportion of the costs of care fall on the state.

All of these factors are essentially fixed and exogenous. They don’t reflect anything that has ‘gone wrong’ with social care - they just increase the demand and, therefore, total cost. Nor can any government do much to alter them, short of adopting weird, dictatorial and coercive policies that no Western democracy would seriously contemplate. They’re the backdrop against which the social care debate plays out.

So who pays?

Well there’s the rub. For all the fury and debate, there are essentially three principal options:

A) Individuals pay for their own care - with a safety net for the poorest. This is the current system, where anyone with assets over £23,2502 pays for their own cost.

B) The state pays for everyone’s care. This is what happens with healthcare on the NHS.

C) Individuals make a contribution to their care - and the state pays the rest. This was the Dilnot system, which enjoyed cross-party support before Theresa May blew it up in the 2017 general election. It proposed individuals should have to pay a maximum of £35,000 - and again, kept the safety net for the poorest, like the current system.

Everything else is just variants on the above3.

We can move around who pays but, at the end of the day, someone’s got to pay.

Look to the right, look to the left…

One of the challenges here - and perhaps one reason why the issue has been in limbo for so long - is that the options above aren’t clearly aligned to the normal political spectrum. There’s not an obvious party which can step in and ‘fix this’.

On the one hand, we might think that (B), the universal state provision model, is clearly the more left-wing model: universal health care was originally a left-wing cause4, so why not universal social care? In practice, however, doing this would result in a massive state hand-out to those with middle and high assets, who currently fully fund their own care.

At the same time, there are plenty of people on the right who argue the current system is unfair because people who have worked all their life and built up savings - that they want to enjoy in retirement, or pass on to their children - have to spend it on social care, while those who’ve been feckless and not saved have their care paid for by the state5. In practice, however, most people on the right also want to cut taxes, which a major increase in public spending makes harder to do.

Others might argue that while treatment for cancer or a broken leg is non-optional - it can only be provided by a specialist hospital - most social care could be provided by family members, and is thus more discretionary. Is it fair that when family members don’t step up to the mark, that other hard-working tax payers should pay the price? Or, conversely, is it fair that people should sacrifice their own careers and lives to provide something that should be a universal service?

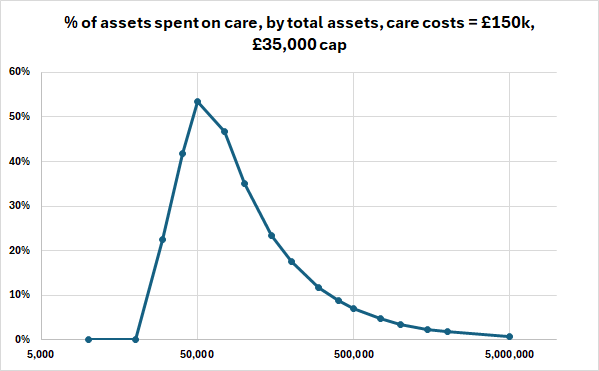

As to whether or not universal provision is ‘progressive’, this is also decidedly non-obvious. Consider the case of someone who spends £150k on old age care6 - that’s approximately five years in a typically-priced care home or, alternatively, some spending on social care in their own home followed by less time in a care home. What proportion of their total assets go on care?

We can see here that, in terms of a proportion of assets, social care costs are likely to be a particular issue for those between around £40,000 and £400,000, all of whom in this scenario are paying over 40% of their assets on social care - and those with between £100,000 and £200,000 are paying over 75% of their assets.

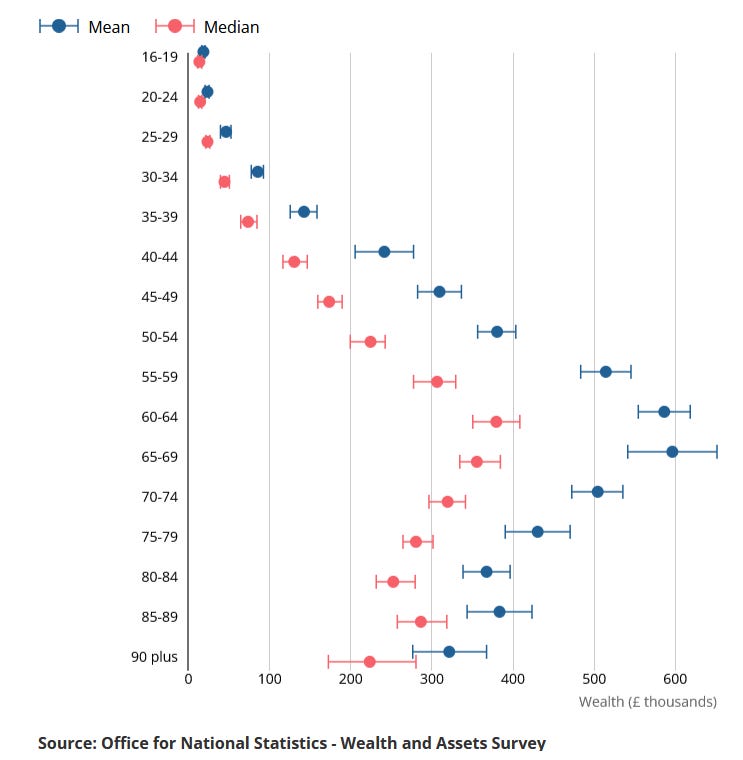

Coincidentally, this coincides very well with median assets of an elderly person - around £300,000 - which equates very much to the hard-working middle of the population. It’s those who’ve worked hard, whether as an electrician or nurse, manager or teacher, truck driver or engineer - who own their own home7 (the average price of a UK home is £289,000) but who aren’t mega-rich.

Hence why so many people care about this.

Moving to Option B would make the biggest proportionate difference to those in the middle of the population - without doing that much for those at the very bottom or those at the very top8. Who ultimately would be better and worse off would depend very much on which taxes were raised to pay for it.

Option C is essentially an attempt to compromise between these different stances - the Government pays more, but not nearly as much more as under Option A9, while individuals still make a contribution. One big advantage of Option C for individuals is also that it takes some of the uncertainty in the system. Social care costs vary dramatically - someone who drops dead at 65 of a heart attack won’t need any while someone who declines slowly with dementia will need a lot. By having a cap, this helps to even this out and lets people plan better10.

But thresholds matter

One interesting fact is that under Option A (the current system), the threshold doesn’t matter very much at all11. This, I think, is one reason why Theresa May’s proposal bombed so badly12.

May’s proposal was essentially exactly the same as the current system - but with the threshold where the state paid for costs raised from £23,250 to £100,000. And yet it was branded the Dementia Tax and was tremendously unpopular. One reason, I believe, is that the change would have helped very few people - and certainly very few potential Tory voters. Remember that over 80% of those aged 70+ own their own house - and almost anyone who owns a house will have over £100,000 of assets - so, in practice, most people would still be fully funding their own care.

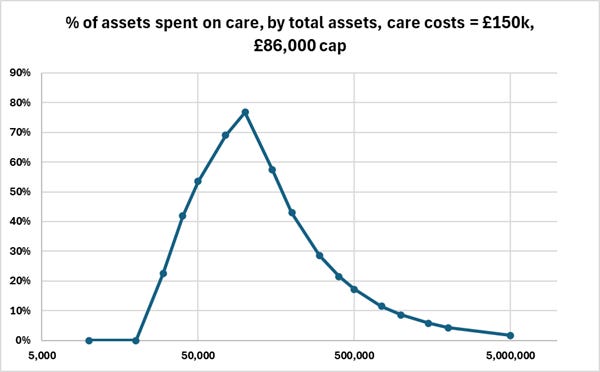

On the other hand, under Option C, where you set the cap really does matter. We’ll look at the graph above again, assuming the same £150,000 of old-age care costs, with the cap set at both £35,000 (the Dilnot proposal) and £86,000 (the Boris Johnson proposal)13.

Cap of £35,000

Cap of £86,000

The £35,000 cap makes a big difference. It shifts the peak leftwards, from c. £175,000 to just £50,000, and it also lowers it a lot, from c. 85% of assets to c. 55% of assets. Those with median assets of c. £300,000 see the share of their assets spent on care drop from 50% to just 23%.

The £86,000 cap, on the other hand, is rather different. The peak also shifts leftward, though less dramatically, but stays high, at just under 80%. Those with with median assets of c. £300,000 still see the share of their assets spent on care drop significantly, from 50% to just 29%, but those assets below about £150,000 see little benefit. It also - obviously - wouldn’t make any difference to anyone who spent less than £86,000 on care, which may be quite a few people.

The lower the cap, of course, the more it costs. A very low cap starts to approach Option A - a fully socialised system, with all the associated costs and benefits - whereas a very high cap may be thought of as more of an insurance policy for the least fortunate.

So how do we solve the problem?

I’d come back to the title: is there a problem to solve?14 It doesn’t seem obviously wrong to me that people should have to pay for their own care, or that the amount someone inherits is lower because of this. Very few people these days move in to a home they inherit15.

Yes, one does want to encourage people to build up assets but any more socialised system will only need to be paid for from general taxation - which will almost certainly need to be paid for by those with the assets, income and potential inheritances who are concerned about the current system.

One potential thought experiment is this. Assuming the sums were exactly the same, assuming you were to inherit money from your parents, would you rather:

Inherit £100,000 less, because this had been spent on old-aged care?

Inherit £100,000 less, because this had been taken in inheritance tax?

For my part, the first seems much less objectionable - though others may feel differently. And while the cost of a new system is unlikely to be levied purely through inheritance tax, this thought experiment does get at the crux of the issue: someone has to pay.

That said, Option C, as recommended by Dilnot, also has a fair bit to recommend it, particularly if the cap is relatively high - say £100k - £150k - to keep the increase in public spending low. Humans really don’t like uncertainty, and there’s even the possibility that providing that certainty might encourage some people to save more - knowing that it wouldn’t all be taken from them.16 It’s certainly a very reasonable option - and the only option hitherto that commanded anything like a consensus.

But ultimately, there’s no such thing as a free lunch.

Making the headling a QTWTAIN.

The median assets of an individual in their 70s is around £300k.

That’s not to say that those variants might not be important. Whether the cap in C is £35,000 or £86,000 (as proposed by Boris Johnson) makes a big difference - and things such as making it easier for payments to be made against the value of a house (which are then reclaimed when the house is sold) could make it much easier for someone who needs some care costs in their home to stay in it.

Even if now clearly embraced across the political spectrum outside of the US.

Though it is worth noting that those who have to rely purely on state care are likely to have worse care.

I’ve been unable to find an average total cost - and, as I say below, this varies greatly by individuals.

80% of people over 70 own their own home.

Technically speaking, those at the top would be saved the cost of their care, but (a) it’s a much lower proportion of their assets; and (b) they’d be most likely paying the most through the increased taxation to pay for this.

I am in two minds about this argument. On the one hand, evening out the impact of random chance across a population is something that Government is great at doing. On the other hand, insurance can also do this.

Unless you raised it really high.

As well as launching it with no pitch-rolling whatsoever into the middle of the General Election, the most hostile possible environment.

We’ll assume the safety-net threshold is unchanged at £23,250 in both cases.

Other than all the other things wrong with the social care system?

As opposed to selling it.

I say this with low epistemic confidence. Most people’s primary assets are in their home, and people already want to buy and own their own home.

Could you make people pay for their own care but offer enhanced IHT relief if care home costs exceed some percentage of the remaining estate.

Wouldn't most married couples each own a half-share of a property? That being the case there will be many home owners with assets of c.£50 - 150k outside London and the South East, assuming no substantial private pension assets.