How elite benevolence hurts the middle

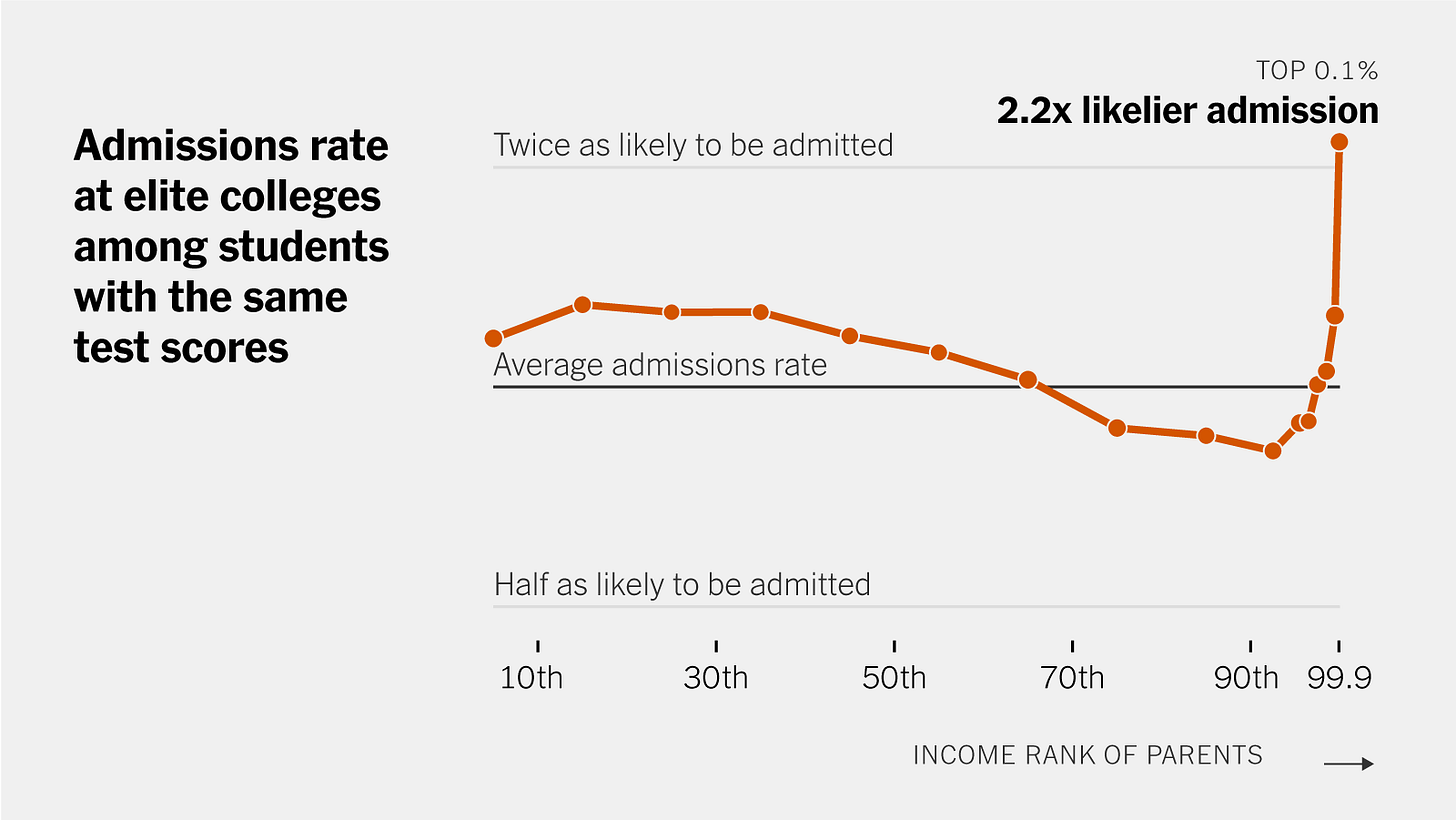

Here’s a chart that did the rounds last year, showing the chance of getting into elite US universities, such as Harvard, by parental income - after controlling for test scores:

The first thing that jumps out at you on seeing this graph is the very high spike for those in the 99th and 99.9th percentile - the top 1% and 1.1%. This is indeed noteworthy: it clearly helps to be rich to go to Harvard.

But look a little closer and something else becomes clear. Those on the 70th - 90th percentile - the wealthy, but not super-wealthy - actually have worse than average chance of getting in. They are notably less likely to get in the than those in the 10th - 40th percentile.

How can this be? In this piece we’ll be looking at how so often it is those in the middle who pay the price for elite1 benevolence - and why this occurs.

But before we do, this post was voted for by paid subscribers (thank you!) as the piece they wanted me to write in the third quarter of this year2.

Every quarter I ask paid subscribers to vote on a ‘long-read’ that they would like me to write for the next quarter. If you want to be able to vote on what should be the final quarter’s piece, I will be sending out the voting form to paid subscribers next weekend, so upgrade now to have your say.

In addition to voting on the topic, if you wish to be able to propose topics for the vote, then you can become a ‘founding’ subscriber, to gain this both ability and my eternal3 gratitude.

So how to explain this Harvard distribution?

Well, Harvard and other elite US colleges have various programmes to support poorer or disadvantaged applicants, including ones targeted at specific groups, such as rural areas. They also - until recently - practiced affirmative action, giving additional places to black students at the expense of white and Asian students; now that this has been struck down by the Supreme Court4 they continue to actively encourage black applicants, who statistically speaking will be from poorer households.

But these colleges also have a whole set of discriminatory measures focused at very rich households: so-called legacy admissions (where the parent has donated substantially to Harvard), ‘Dean’s List’, and children of faculty5. In fact, a recent study found that fully 43% of white students admitted came from these categories (plus athletes). This does two things:

Tilts the admissions towards white applicants against black, Asian, Hispanic and others (who make up only 16% of legacy admissions).

Given that Harvard also practices affirmative action (or now very similar practices), guaranteeing a minimum proportion from that ethnic group, it also squeezes the places available for non-legacy/athlete whites.

Legacy admissions, in particular, are tilted towards the very rich, meaning that the entire rest of the white population is competing for just 57% of the places. The final result ends up something like the table we see above: the best off are the very wealthy, who protect themselves through legacy places and ‘Dean’s list’ admissions. But the worst of are those who are not rich enough to take advantage of this - but neither fall into any category that qualifies for some other type of special advantage, whether based on class or race. In other words, the middle - the 60th - 90th percentile, in this case - and other groups; notably Asians, who are admitted at a far lower rate than they would deserve on merit.

In the UK, fortunately we don’t have legacy admissions. Though it’s not perfect, our admissions system remains significantly fairer than the US. But even here, it is often the middle who pay the price for elite benevolence.

Scotland has by far the strictest and most discriminatory university access regime in the UK, to the extent that last year, no ‘non-disadvantaged’ applicants - no matter how good their grades were - were offered places on some of the most prestigious courses, such as law at Edinburgh6.

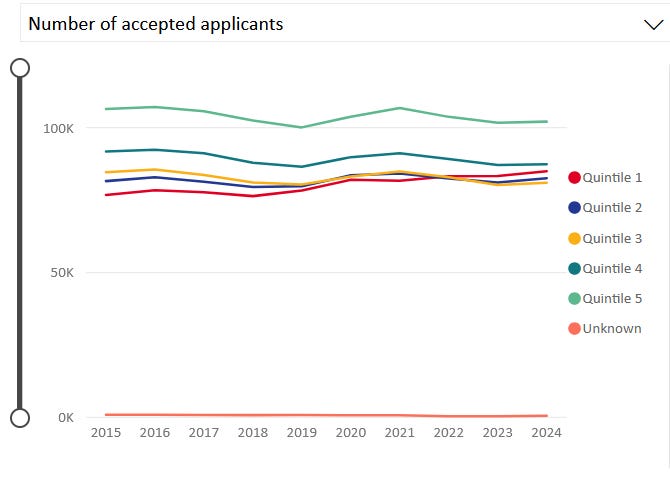

Now, the top do pay some price here - but if we look at the stats, we see it is the middle who have paid the highest price. The chart below shows that those from the most disadvantaged quintile (quintile 1) are now more likely to be accepted than quintile 2 or 3, and almost as quintile 4 - but the significant gap between quintile 5 and 4 is just as big as it was ten years ago.

Who gets which school?

Let’s take a more hypothetical example: access to good state schools. The current situation allows wealthy people to effectively buy a place at the best school in the area by purchasing a house in the catchment area7. There is a high premium for houses in the catchment area of outstanding schools (in 2017 ONS estimated this at 6.7%; more recent estimates argue it could be over £100,000) which leads to poorer kids being squeezed out and the rich getting their choice of school.

One common idea in elite discourse is to give children on free school meals (FSM) automatic priority at schools. This is not a stupid idea. But what’s the result?

Firstly, and most obviously, a lot more kids on FSM get into Outstanding schools. That is good on the merits – at one level the policy clearly works. But who pays the price?

Let’s imagine an Outstanding school had a 1 mile catchment area. Pre-policy, let’s say it had 5% of kids on FSM. After the policy, let’s say that goes up to more like the national average, or 25%. The catchment area shrinks accordingly, to say 0.8 miles. What happens then? People who can will still pay a premium to live in that catchment area, but the number of places available based on distance has shrunk. By supply and demand, the premium to buy a house in the catchment area increases. Who can no longer afford it? Those in the middle. Who will still be getting in? Those at the top.

The net result, therefore, is a direct transfer of benefit from those at the bottom of the segment who could previously afford it - the middle, on an overall scale - to the bottom quartile of society. It’s a transfer from the middle to the bottom, with the top unaffected. At one level, this makes society more equal, but it leaves the richest untouched.

Note that there are means of helping FSM kids – and those in the second quartile from bottom, too – that would harm the richest. A lottery, for example, would give children from all walks of life who apply the same chance8 of getting in. This is an entirely workable approach - and, indeed, most Charter Schools in the US are required to select their intake this way.

The top indisputably lose from this, as does everyone with an above average chance of getting in, and all those with a below average chance – not just those on FSM – gain. Now, there are valid reasons to prefer distance-based catchment areas to lotteries: it’s nice for kids in the same neighbourhood to go to the same school, and bussing/driving kids all over town is deadweight for everyone involved. But these alone can’t explain how absent lottery solutions are from the discourse. What is far more relevant is that most of those in the elite policy discourse are personally unthreatened by the FSM proposal - but would be, directly, by the lottery approach.

Elite benevolence is not the same as luxury beliefs

In case anyone thinks I am being too hard on elite benevolence9, it’s important to emphasise that elite benevolence is not the same as luxury beliefs.

Luxury beliefs refer to the situation when privileged people adopt a belief that, if enacted, causes harmful consequences for other people, but no or minimal consequences for them. Examples might be ‘defund the police’ (fine for those in gated communities with private security) or ‘family structures don’t matter to children’ or ‘drugs are harmless entertainment’.

By contrast, elite benevolence actually does work. Giving kids on free school meals preferential access to schools or university does actually help kids on free school meals. Affirmative action does help black people. It is simply that the cost of this help is not - primarily - being paid by the top, but by the middle.

How does elite benevolence work?

Lest anyone think I am crazy10, I am not suggesting there is some grand classist conspiracy to plot and adopt these positions. This all happens at a much more subtle level.

There are usually good reasons for or against most policies, and this works with self-interest, at an unconscious level (using the ‘must I believe’/’can I believe’ paradigm) to produce certain results. Organisations - government, civil society, the media - are made of people and what issues are in their personal Overton window depends greatly upon not only their own experiences, but upon those with whom they work, socialise and associate. It is much easier to promote or advocate a policy if no-one you know well will be badly impacted by it, than if you know it’s going to badly impact Alice and Bob in your team at work, while your neighbours Caroline and Daniel, who you have dinner with once a month, also strongly oppose it.

During the passage of the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act, there was much wry commentory on the relative amount of time that MPs spent debating the impact on Oxbridge colleges (total student population: just under 50,000) vs the amount of time they spent debating the impact on FE Colleges11 (total student population: 1.6 million).12 It is absolutely no surprise to me that universities first started to seriously and systematically discriminate against private school applicants13 - not to mention the VAT on private schools plan - shortly after they had increased fees to a level that priced out the majority of mid-senior civil servants, broadsheet education editors and MPs without independent means. Turns out lawyers, bankers and international students aren’t a sufficiently broad caucus to keep you afloat.

More broadly, the rich will always be more threatened by the middle than the poor. Given all the other many challenges of family background, lack of accrued wealth, social capital and so on, it is very hard for those in the bottom quartile to get to the top 5% in anything like the kind of numbers to threaten the existing elite hegemony. The odd one may make it - the shining stars of elite benevolence - but very few.

The middle classes now, that’s another matter. They have the numbers and the financial cushion to be a genuine threat. Open up opportunityies here and elite hegemony will crumble. Equally, the middle classes are most threatened by increased social mobility from the poor. In a real sense, it is in the elite’s interests (not to mention boosting their moral self-esteem) to favour measures that promote the poor at the expense of the middle class, and for the middle class to favour the opposite.

This explains the vitriol directed at grammar schools by the elites, despite more positive views amongst the population as a whole. Grammar schools almost completely close the attainment gap between rich and poor; however, despite this grammars do very little for those on Free School Meals, as very few get in (and those who don’t get in appear to do slightly worse).

On the other hand, grammar schools function as a great leveller between the middle classes and the top. They are the surest way a bright child from the 50th - 80th percentile can get an academic education comparable to that of a top private school - and significant numbers of children from these cohorts do get in. In addition, unlike the comprehensive system of house-price selection, the top cannot simply buy a place. Certainly, tutoring helps, but there are rapidly diminishing gains from this: £2k on tutoring may do a lot to get a marginal candidate over the line, but £200k of tutoring can’t make a dumb kid smart. So the rich can’t buy their way in, and the middle class get access to schools that are academically as good as the top private schools, breaking their strangle-hold of the elite on top education.

If giving FSM kids priority to comprehensive schools is a transfer from the middle to the poor, leaving the rich untouched; grammars are a transfer from the rich to the middle, doing little for the poor. It is no surprise which one elites support and which they oppose.

Elite Benevolence Beyond education

All the examples given so far have been in education - but while education provides some of the most obvious examples, we can see examples of elite benevolence elsewhere. If increased spending on public services or benefits are paid for by raising income tax or freezing the thresholds (the higher rate of income tax kicks in at £50,000), rather than by taxing wealth, capital gains or non-dom tax breaks14, this would be an example of elite benevolence: the middle paying the price for helping the poor.

Arguably, elite benevolence was a strong feature of the last Conservative Government15, perhaps particularly the first nine years. There was a genuine focus on those at the bottom16, with major increases to minimum wage, the introduction of pupil premium and the increase in the international development budget to 0.7% of GDP. At the same time, the middle classes were repeatedly hammered, through mechanisms such as the trebling of tuition fees, the means-testing of child benefit and cuts to real-terms public sector professional pay and pensions.17 The top, meanwhile, were relatively untouched18, with non-dom status, wealth taxes, trusts and other perks of the elite firmly out of bounds.

Though Brexit clearly played an important role in alienating the professional classes of the ‘Blue Wall’ in the recent Conservative electoral collapse, the repeated failure to make their life better - and, indeed to visibly be making their life worse - is an underexamined factor as to why this formerly reliably Conservative bloc turned against the party. Yes, values and ideology matter for some, but personal economic interest also matters. The double whammy of both is hard to overlook.

So which is more important for reducing inequality: levelling the gap between bottom and middle, or middle and top? Both in a very real sense do reduce inequality - and both improve the lives for some people.

In my view, our society currently focuses far too much on the former, doing nothing, or actively opposing, social mobility between the top. Too many serious, thoughtful, policy commentators will evaluate initiatives solely on the basis of what impact is has fo those on free school meals, or on the bottom quintile or quartile.19 And yes, this absolutely matters. But if you ignore the impact on narrowing the gap between middle and top - if you systematically neglect or actively undermine schemes, policies and institutions that will help here - then you are simply preserving elite hegemony.

There is in fact a strong argument that we should particularly care about the make-up of those who reach the top, for these people have an outsized impact on our society as a whole. Members of Parliament, High Court Judges, FTSE100 CEOs, top scientists and leading journalists - all of these disproportionately shape society and how we live our lives. This is broadly recognised when it comes to discussions of race and gender: there are targets for women or ethnic minorities on boards. So broadening routine access to this elite tier beyond the top 1-5%, to the top 10-50% of society, would have major advantages.

And yes, we also want to keep supporting on those at the bottom, to break the cycle of poverty and to give everyone at every level of society a leg up. But when a new policy is being put forward, always think: who really pays the price for this? And rather than a systematic elite benevolence that harms the middle, better to focus on creating opportunities that allow people to fulfil their potential at every level: bottom, middle and top.

This was the third-quarter long-read voted for by paid subscribers. If you would like to vote for this quarter’s long-read, upgrade to ‘paid’ below before next weekend.

Read, Subscribe and Share.

Exactly which group is in ‘the top’, ‘the middle’ and ‘the bottom’ will vary depending on the examples looked at: what is consistent is that the top is more advantaged than the middle, which is more advantaged than the bottom. The most common cases, however, will see the top being at least the top 10% (sometimes the top 1%); the middle typically the 50th - 90th percentiles - what in Britain is often called ‘the middle classes; and ‘the bottom’ typically those in the bottom quartile or below - similar to the proportion in the UK who are eligible for free school meals.

The sharp-eyed will note that, once again, it is slightly late - but it is here.

Strictly speaking, not eternal.

After a group of Asian applicants took them to court, demonstrating that they gained proportionately far fewer places than they should by merit.

Academia doesn’t pay well, but Harvard faculty are still pretty rich by national income standards.

Under the Scottish system, universities set a ‘minimum entry standard’ for each course and then all disadvantaged students who exceed that are automatically admitted; only if places are left after that are students not classified as ‘advantaged’ admitted. One could be on the 50th income percentile and be the smartest person in that subject in the UK - Gold on Maths Olympiad, published papers you name it - and not have a chance of getting in.

Full confession: we have done this.

One would still have to apply for the school, giving an advantage to those who have parents who care about this - but there is very little way of avoiding this.

Though I am being somewhat hard.

Anyone who doesn’t already think that, that is.

Hint: the FE Colleges didn’t get more airtime.

Under a Conservative Government, no less!

As always, there are legitimate economic reasons to oppose increasing these taxes. Or indeed any taxes, from our current situation of record-high tax as a share of GDP. But it is a question of who pays.

In a specifically right-wing sense, one could call this philosophy Patrician Conservatism.

Though not at the very bottom, as benefits were squeezed.

The relentless hostility towards ‘gifted and talented’ schemes or initiatives in many state schools - and from the Department for Education - also does not help here.

Yes, the top were also affected by these things. But the wealthiest 10% pay their tuition fees upfront, and losing child benefit matters a lot more to someone on £70k than £170k or £700k.

The phrase I loathe most in social mobility discourse is ‘those kids will be OK anyway’. It’s a wonderful salve of conscience for those at the top - who have access private schools, top comprehensive catchment areas and networks of professional connections - to justify doing nothing for highly able kids from decent families - the skilled working class or ‘normal’ middle class - who will be alright, in the sense of not being in poverty, but have none of those advantages and rely on a great education to break into the top.

By using the UCAS admissions data as a whole you are not discriminating between different Universities. I suspect that if you separated University admissions into groups: Oxbridge, the Russell Group, and Million+, you would find quite a difference between admissions by quintile to the different groups. In particular, I suspect that you would find proportionately more from the lower quintiles going to the Million+ universities. If you can do this, it would be an interesting exercise.