Contra Bret Devereaux on Fascists being Bad at War

Embracing myths about our enemies' ineptitude is comforting - but dangerous.

My favourite historian, Bret Devereaux, has written a widely read post, and an even more widely read Twitter thread, arguing that fascist societies aren’t just bad at everything sensible people value, but that they’re bad at war too.

Now I love Devereaux’s work, and have learned a lot from him about everything from ancient Greece and Rome to how accurate Tolkien was about logistics, not to mention far more than I ever thought I wanted to know about how bread was made in antiquity. And his motive for arguing that fascists are bad at war is the best possible one: he’s worried that some people are attracted to fascism because they admire it for its military strength, and wishes to deter them: as he correctly says, “society as a whole benefits from having fewer fascists, so the exercise of deflating the appeal of fascism retains value for our sake.”

But good motives don’t justify saying things that aren’t true - and in this case, the message he’s pushing is one that’s actively dangerous, particularly in a world where our democracies face increasing threats from authoritarian, revanchist nations such as Russia and China.

Before we go on, I should be explicit that there is one point on which I am in full agreement with Dr. Devereaux: that is that fascism is bad. It is a vile, loathesome ideology which causes misery to its own citizens and - typically - embarks upon wars of aggression which cause great misery to others. Alongside Communism, no other ideology of the 20th century has been responsible for more death and suffering. In arguing that fascism can be good at war I am not arguing it is ‘good’ in any other way; simply arguing that it can be dangerous, and its threat should not be underestimated.

It’s the most tempting thing in the world to believe that those we disagree aren’t just wrong, but stupid. And not just stupid, but inept, ineffectual, failures, pathetic. All Brexiteers are stupid and uneducated; the left have no brains; Trump’s too crazy / Biden’s too old to win an election. Twitter will be bankrupt in a year now Musk has bought it; Go Woke, Go Broke1. Well, how are those working out for you?

We’d love to believe that fascists were, in addition to their many other failings, bad at war. Wouldn’t that be convenient? We wouldn’t have to fear them; we could laugh at them instead. But is it true?

Sometimes it is true. Fascist Italy was absurdly bad at war. Whilst other European countries had been carving up Africa as if it were butter, Mussolini took nearly two years and lost tens of thousands of troops conquering Ethiopia. In the Second World War, Italy’s performance consisted of attacking someone (the British in North Africa, then Greece), being comprehensively beaten despite massively outnumbering their opponents and then having to get bailed out by the Germans2. It is indisputable that at least some fascists are bad at war, and that fascism is - fortunately - no guarantee of military prowess. But are they always bad?

Devereaux’s argument rests primarily on the fact that the two principal fascist countries, Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy3, both lost the major wars they started and were, fairly rapidly, wiped out of existence. To quote, “Remember that major war the fascists won? Of course you don't, they almost always lose.” And if one thinks of other fascist countries - Spain, Portugal, arguably Argentina - they aren’t known for winning major wars either.

It is, of course, true that Germany and Italy lost World War 2. But is this sufficient to say that they were ‘bad at war’? Germany certainly won a lot of battles at the beginning, defeating one nominal peer (France), numerous other countries and rapidly conquering most of Western Europe. Were they bad at war? Were they good at war (i.e. better than France), but Britain and the United States even better? Or were they good at war, but took on so many opponents at once, that they became overwhelmed?

For Devereaux, the question is meaningless. He correctly states that “war is an activity judged purely on outcomes”, and rightly rejects metrics such as how flashy or technically advanced one’s equipment is, the ratio of kills inflicted to suffered, or who has the best generals. But he then goes on to argue:

Starting a war in which you will be outnumbered, ganged up on, outproduced and then smashed flat: that is being bad at war.

Countries, governments and ideologies which are good at war do not voluntarily start unwinnable wars.

He then says:

The most fundamental strategic objective of every state or polity is to survive, so the failure to ensure that basic outcome is a severe failure indeed.

This fundamentally confuses success as a state to whether or not that state is good at war. Survival of the state is indeed the fundamental objective - but that survival depends on more than war. To say otherwise is to reduce the entire function of the state to war; a reductionist fallacy. War may be the continuation of policy with other means4, but it does not follow that policy is a mere branch of war. A state may fail for many reasons, and being bad at war is only one of them - even if the ultimate defeat comes via war.

Devereaux even recognises this himself, in non-fascist contexts. In his latest post, he explicitly distinguishes between how good the Seleucid armies are at fighting the Parthian armies - how good they are at war - and the overall success of the Seleucid state against the Parthians, which is complicated by other factors.

Now that is a real weakness of the Seleucid system – it is a problem with Hellenistic monarchy that it is so easy to destabilize it – but that is not the same as Hellenistic armies being categorically incapable of coping with horse archers.

To give a simple, non-fascist, example: Napoleon is widely - and correctly - considered to be good at war. But Napoleonic France was defeated in a mere couple of decades. He was good at war, but less good at diplomacy and foreign policy; he united Europe against him and, despite his military prowess, was defeated (twice). But to summarise him as ‘bad at war’ would be absurd.

So, back to the fascists

Devereaux’s argument on why Nazi Germany was bad at war rests heavily on two points. Firstly, that it rashly declared war on both the United States and the Soviet Union, which were both monumentally stupid decisions, an assessment with which I would not disagree.

Hitler’s decision, while fighting a great power with nearly as large a resource base as his own (Britain) to voluntarily declare war on not one (USSR) but two (USA) much larger and in the event stronger powers is an act of staggeringly bad strategic mismanagement.

The second is that, in consequence to having declared war on countries with much larger industrial bases, Germany was ‘outnumbered, ganged up on, outproduced.’ Which is also true. But neither reflect being ‘bad at war’.5

To take the second point first, the United State’s vast industrial base reflected the fact that the USA was ‘good at peace’. It had a thriving economy, great technology and strong factories which allowed it to outproduce every other nation on earth. Now, if two countries had similar size industrial bases, but one was much worse at turning it over to military production6, I might accept that as being bad at war. But the strength of a country’s industrial economy prior to war breaking out is a measure of success at peace, not at war.

We can see this clearly by an analogy on a subject close to Devereaux’s heart: computer games. In many of these games, certain nations or leaders will have particular bonuses: an ‘economic’ nation will get a bonus to trade, a ‘scientific’ one to research and a ‘military’ one to military strength. Now, the ‘economic’ nation might end up winning, because it uses its superior economic strength to outproduce and crush the ‘military’ one. But we are all quite comfortable here saying that one nation is good at war and that one good at the economy - and we know that the nation with the economic bonuses had better build up strength in peace time as, on a 1:1 basis, it will be outmatched in a fight against the nation that is ‘good at war’.

As to the other point, about Germany starting too many wars, let’s consider another analogy: that of a boxer.

Imagine a boxer who won almost all of his one-to-one bouts. Against anyone in his weight class, he’d take them down - and often beats those in heavier weight classes too. But he’s also cocky. Sometime he’ll challenge multiple opponents at once, or keep challenging fresh opponents when he’s tired after multiple bouts. One time, he first defeated multiple opponents in a simultanous match, and challenged two super-heavyweight boxers at once, fought them to a near standstill for 25 rounds, before going out for the count - with injuries bad enough to put him out of boxing for good.

Would we describe such a boxer as ‘bad at boxing’? Or would we say he was good at boxing, but crazy at choosing opponents? I’m confident most of us would say the latter. And - and this is the key point - to describe him as ‘bad at boxing’ would be dangerously misleading. If you thought he was ‘bad at boxing’ you might not bother to train to face him. If you thought he was ‘bad at boxing’ you might send a rookie out to face him, as an easy warm-up. And those could be fatal mistakes.

In short, Devereaux's argument only works if one conflates everything a state is and does into whether it is ‘good at war’.

Devereaux makes an interesting suggestion that fascist regimes are particularly bad at starting stupid wars, due to their (mistaken) valorisation of war and dependence on the dictates of an unchallenged leader. This feels highly plausible and it may be the case that - even had Hitler not invaded the USSR and declared war on the USA, but instead simply conquered Britain in 1942 - Nazi Germany would not have endured, but instead have, sooner or later, brought about its own destruction, rather than enduring in the chilling societies depicted in Fatherland, The Man in the High Castle or In the Presence of Mine Enemies. But we should not forget that in the real world, they first brought Europe to its knees.

‘Good enough at war’

I don’t know whether fascist regimes are, on average, better at war than regimes run by other forms of Government. I don’t know whether, in a technical sense, Nazi Germany was ‘bad at war’, or was ‘good at war’ but that its adversaries were even better: the United States in the 1940s was pretty phenomenal at war, and we Brits had our moments too.

What I do know is that they were good enough at war to smash France, conquer most of Europe and come within a hair’s-breadth of defeating Britain7. I know they were good enough at war for it to take an international coalition of the strongest nations on the planet to defeat them, and then only at the cost of millions of lives. I know they were good enough at war to take and hold territory for long enough to perpetrate the monstrous crime of the Holocaust, slaughtering over six million Jews and others.

If that’s being ‘bad at war’ then, frankly, I don’t care what being ‘good at war’ looks like.

In a world where authoritarian, revanchist nations8 are flexing their muscles, and the world’s democracies are struggling to respond, it is tempting to think that we will win by default. That ‘fascists are bad at war’. But that way lies complacency and defeat.

Devereaux, to be fair, accepts that we should avoid complacency, and accepts that ‘fascist governments can defeat liberal democracies if the liberal democracies are unprepared and politically divided.’ But even, he still misses the mark. He asserts that ‘fascist and near-fascist regimes have a habit of launching stupid wars’ - but while some of their wars may be stupid and unwinnable, not all of them are, or will be. And he encourages us to doubt fascist displays of strength, saying:

Because being good at war is so central to fascist ideology, fascist governments lie about, set up grand parades of their armies, create propaganda videos about how amazing their armies are.

Well, perhaps sometimes that is the case. But other times it isn’t. It is hubris to assume that your adversaries are weak. Before the War, Western nations made fun of ‘primitive’ Japanese planes made of ‘wood and paper’ - only to discover in due course that the Zero was one of the most effective planes of the war.

Right now, Russia has invaded Ukraine - and after an initially strong response, the West is at severe risk of being divided politically. Even more worryingly, Russia - a country with the GDP of Italy - appears to be outproducing the entirety of the West in terms of munitions production. Our stockpiles have been drained and Ukraine is feeling the lack on the battlefield. Russia could still win this war (though I sincerely hope they don’t). And that’s the junior partner of our adversaries.

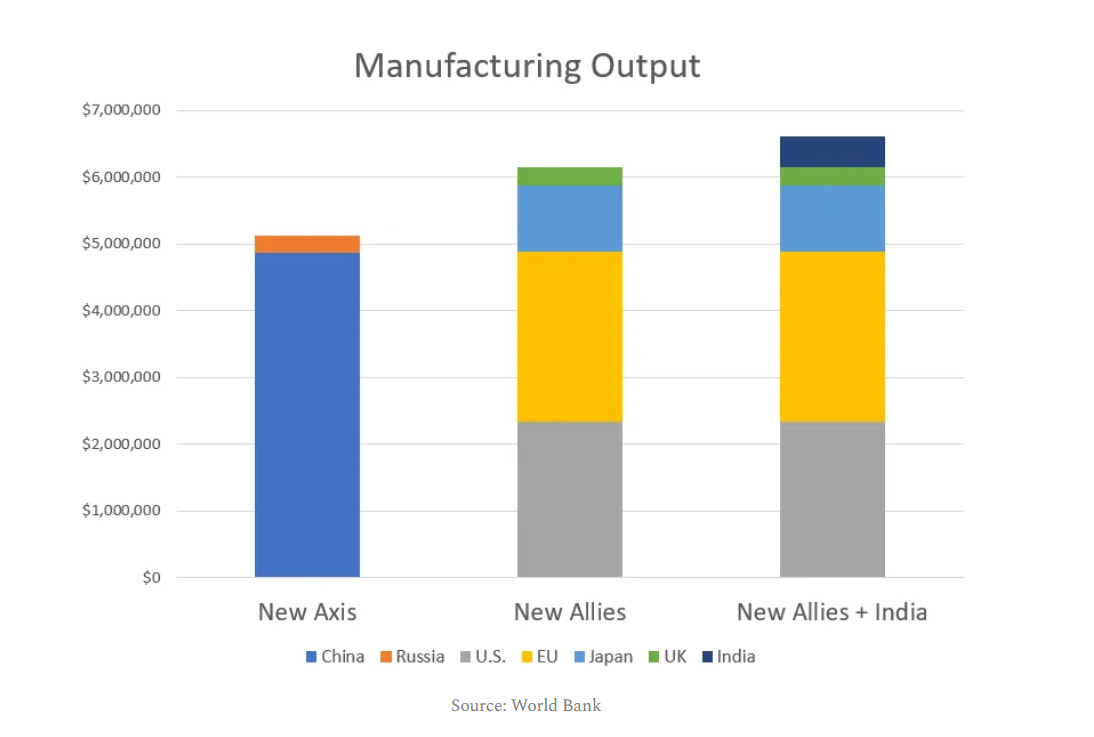

China, meanwhile, has a manufacturing capability almost as large as the entire West combined, is carrying out a full spectrum challenge to Western influence and is rapidly building ships.

We have no space for complacency. At one point in Herman Wouk’s The Winds of War, a novel set around the outbreak of the Second World War, one character says to another9 that now they will find out whether or not democracy is truly better. The second character is startled; surely they know that democracy is better. “But is it better at war?” the first retorts. “That’s what counts now.”

Fortunately for us, in the Second World War, the democracies did - eventually - prove better at war. But if we wish that good fortune to last for the future, we had better not be complacent, nor console ourselves with comforting myths that ‘fascists are bad at war’.

I know that one can find some specific examples of companies going broke after going ‘woke’. I know that one can also find examples of companies prospering. I’ve yet to see any serious analysis that there’s a correlation here.

Devereaux uses the term ‘fascist’ in a (correct) technical, fairly narrow sense, not as a synonym for authoritarianism, so I will do the same.

Drink!

He also argues that the Wehrmacht was not the invincible machine it is sometimes depicted as, but made a number of mistakes, particularly in Russia and later on in the war. I have no disagreement here; Germany’s adversaries were also good at war.

As the West, tragically, seems to be unable to match Russia on production of munitions.

And would have almost certainly done so without US aid, lend-lease and so forth.

Whether or not they are actually fascist.

I regret I cannot find the precise quote, and it is an 800 page book - and it could even be in the sequel.

I also disagreed with Bret's essay, but for completely different reasons.

We all agree that facists can be extremely successful at battles, as you've laid out below. Bret doesn't make this explicit, but his argument appears to accept this point.

What I think Bret adds to the picture is "don't confuse battlefield success with winning wars. Strategy matters. A lot. And facist nations are constitutionally bad at it." I think this is a good point. Furthermore I think facism's battlefield success and strategic hubris are intertwined, both emerging out of their distain for their opponents, so that it's either hard or impossible to produce a 'fixed' facism that is genuinely good at war, not just at winning battles. I think this point is very relevant to anyone tempted by facism as a solution to the weakness of liberal democracies.

Where Bret's essay disappointed me was that it's an explicitly ad hominem argument aimed at facists that keeps taking time out to sneer at facists. Nothing undermines your argument like being rude about the group you're trying to persuade! As a result I think this is an argument that will in practice only be read by non-facists, for whom I agree the take home message ought actually to be "Be aware that facists can be very strong on the battlefield, and might start a war with you even if it is sheer lunacy to do so."

Thanks, this was an interesting read