Barbarians at the Gate

What can we learn from the fall of the Song Dynasty?

Not every fall is Roman.

I’m currently working on a longer piece about my experience of being a special advisor, but as that is currently growing like Topsy, in the meantime I thought I’d share a few musings on why the fall of the Song Dynasty may be a better analogy for Western malaise than the Roman Empire.

Rome’s decline and fall is the touch-point for Western thinking about this subject. It’s our own history, immortalised by Gibbon and countless others, and the basis for many fictional falls in fantasy and science-fiction, such as Asimov’s Foundation series. But civilisations can stutter and fall for many reasons - and it may be well for us to remember them.

But if we’re honest, Rome’s problems aren’t all that like those the West is facing. For all of our challenges, frequent civil war or succession crises are not one of those. General Petraeus did not seize control of the US army in Afghanistan and march it on Washington. Rival countries in NATO are not duking it out to become Secretary General. Our countries are democracies, with peaceful transition of power not a significant worry1.

Nor is our economic growth is not stuttering because our military expansion has stalled, and with it supplies of tribute, gold and slaves back to the imperial capital. Conquest stopped being profitable at least a century ago. Nor are our enemies waves of barbarian tribes undertaking mass migration. I’m not saying there are no similarities - but it’s not the obvious comparison.

I’ve written before about our current malaise - the stagnant growth, failure to build and strangling bureaucracy that chokes both the public and private sector. Almost twelve months on, I’d add our collective failure to make enough munitions to supply Ukraine, meaning a nation with the GDP the size of Italy is somehow outproducing the entirety of the West. And we’ve seen how we cannot count on a miracle to deliver us at the 11th hour; the Foundation Myth is just that - a myth - and rich countries can become middle income ones2.

And it strikes me that the fall of the Song Dynasty may offer better lessons for us than the fall of Rome.

For those unfamiliar3, the Song Dynasty ruled China between 960AD to 1127AD4. Following its defeat by the invading Jin, it lost control of the northern half of its territory - the heartlands of China - and continued as the Southern Song Dynasty until 1279AD, at which point it was conquered by the Mongols. I’m focusing here on the fall of the ‘main’ Song dynasty.

Like the West today, the Song dynasty was immensely wealthy. Song China had presided over several centuries of economic growth was vastly richer than the whole of Europe - and all of its near neighbours. It was a time of technological innovation, paper money was invented, the silk and iron industries boomed. So how did it fall? And why I am comparing them to us?

I should first clarify that I am not making a 1:1 comparison. I do not expect us to be immediately overrun by steppe-nomads5. But how did they become weak?

It seems that many of their strengths had become weaknesses, frittering away their wealth and power in internal disputes rather than strengthening themselves. The meritocratic civil service, once a great source of strength, had let to a situation in which scholar-officials held sway and the military fell into lower renown. Political disputes between different factions at court, whether on trivial matters or on serious economic reform, consumed decades - often with little progress. Sound familiar?

Similarly, many of the matters that are paralysing the West are based upon the soundest of principles and good intentions. Planning law, introduced to prevent a free-for-all and to protect nature is now preventing us from building not just the houses we need, but the wind turbines and solar farms required to tackle climate change. A host of well-meaning regulations are driving up costs (child care) and stifling growth. When faced with difficult decisions, again and again we choose the path of short-term comfort over long-term investment - or simply put the decision off all together.

Most fundamentally, they were unable to set aside their own internal preoccupations to defend against external foes. They preferred to pay tribute - a matter about which Kipling, had he lived a few hundred years earlier would have had something to say6. The Sixteen Prefectures, a region along the Great Wall were lost, and not retaken, leaving their heartlands open to invasion. The inadequacy of their army in warfare was shown up again and again - until eventually, seeing their weakness as they floundered in a joint campaign against the Liao, their erstwhile allies the Jin, turned south and conquered them.

After visible failures to achieve our military objectives in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, and a decade-long appeasement of Russia, one might have hoped the invasion of Ukraine would be our wake-up call. And indeed, for the first two years NATO rallied wonderfully, sending aid and armaments to Ukraine.

Yet what we contributed, we contributed out of our abundance, not out of our need. With honourable exceptions - mainly those on the front line, such as Poland - we are running down our stockpiles, not rearming, nor even replacing the munitions as fast as we use them. US support is shamefully stranded in Congress. Yet Europe alone has a GDP more than ten times as large as Russia, a population five times larger and ample access to all the raw materials it could need. How can we allow them to outproduce us? Yet it is happening. As we see Ukraine forced on to the defensive due to lack of materiel, while Russia ramps up its rearming and recruitment, will Ukraine be our Sixteen Prefectures? And if it is, what will we do then? Shrug and wait for the next crisis?

Nor is the situation better in the Pacific. China is rapidly expanding its navy - growing at a much faster rate than the USA - and has the capability to build ships significantly faster. “The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) surpassed the US Navy in fleet size sometime around 2020 and now has around 340 warships, according to the Pentagon’s 2022 China Military Power Report, released in November. China’s fleet is expected to grow to 400 ships in the next two years, the report says.” I’m no military expert - and I’m pretty sure the United State’s fleet is still stronger, for now - but this doesn’t look good.

I am not suggesting that we are facing another outbreak of global war. But the malaise and complacency with which we respond to such events, to grow our economies, or to pursue objectives that enjoy broad, widespread support - whether that is affordable homes and childcare, Net Zero or the defence of our allies - says worrying things about our state capacity. And some of our adversaries appear much more willing to put the power of the state behind their objectives.

Objections anyone?

One argument would be to say that this is not the first time the West has appeared on its knees. The democracies were painfully slow to recognise the threat of Nazi Germany and Japan - and only just began rearming in time. In August 1941, the United States Congress avoided by a single vote abolishing the draft. That’s true - but on the other hand, World War Two was a mighty tight thing and I’d rather not go that close to the wire again.

Another, more compelling argument, is that it is not the West facing malaise, but only Europe7. While we are struggling, the United States is powering ahead, on energy abundance, economic growth, infrastructure, tech and more.

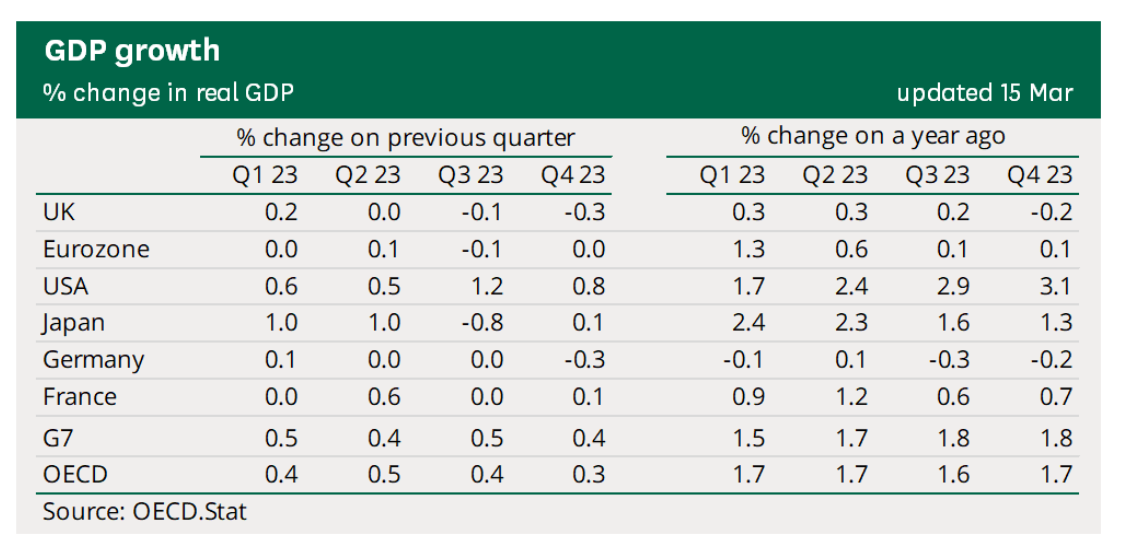

This isn’t just a short-term thing: the United States is powering ahead:

I’m willing to buy that - but the US’s domestic political difficulties bring their own weakness, as the military aid package to Ukraine stalled in Congress shows. And it doesn’t absolve the UK, or any other European country, of kicking themselves into gear economically. Any alliance is stronger when all its members prosper.

And finally…where are the babies?

The Song Dynasty is far from a perfect analogy for our current situation. But in examining our own situation it is insightful to look for other examples of malaise, decline and fall, beyond that of Rome. If we can only draw a lesson or two from the Song, it is worth it.

For in one area we face a challenge which almost no historical civilisation or nation has faced: a birthrate in stark decline. In the UK it has just fallen below 1.49 - well below the 2.1 ‘replacement rate’ - and appears to be in free-fall. In South Korea it is a terrifying 0.72, a number which means for every 100 Koreans alive today, there will be fewer than 5 great-grandchildren. A 20-fold reduction in population in just three generations - about a century is unheard of; if it occurs, it will be a collapse that matches the worst in history8.

I have no idea what to do about this. Birthrates are in decline in social democratic Scandinavia, with gender equality and abundant cheap childcare (Norway 1.5, Sweden 1.65), in capitalist America (1.66), in theocratic Iran, where women are oppressed (1.69), in traditionally valued Japan (1.30), in Catholic Italy (1.28), in poverty-stricken Bangladesh (1.98) - and pretty well everywhere else you can think of. In the short-term, this is good: we know longer have to worry about what could have been very real challenges of over-population and pressure on resources (water, food, land). But an ageing population brings headaches all of its own, most of them stemming from the worsening dependency rate. And at a most fundamental level, a culture that cannot reproduce itself dies.

In this, we face a challenge that is new in all of history. The Song, the Romans, the Byzantines and the Maya had many challenges - but not this one. But while that we grapple with that, perhaps we might contemplate the Song, and others, to see how we can avoid their fate.

The events of January 6th notwithstanding.

And middle-income countries poor ones.

And I do not remotely claim to be an expert.

The link to wikipedia is shared with a high degree of caution. Wikipedia pages on Chinese history demonstrate a high degree of curation that suggests that - unsurprisingly - the CCP is taking steps to control the narrative of China’s history. For example, despite the Jin, Western Xia and Mongols being clearly culturally distinct from China - these were invasions from beyond the Great Wall; the Mongols were steppe nomads - the wars are presented as a dispute between Chinese dynasties, similar to the conflicts during the Three Kingdoms period. I’m confident there are many other subtle shadings that my history is not expert enough to spot.

Yes, I know, the Jin weren’t actually nomads. The Mongols were.

Including both the EU and the UK.

An interesting post! I think you might enjoy reading 1587, A Year of No Significance (about the Ming, rather than the Song, but with some points of contact here).

Worth noting that, because of a lot of archaeological work since the 1970s, it now seems fairly clear that the Roman Near East was very economically prosperous in the 4th-6th centuries (primarily, but not exclusively an agrarian phenomenon). Things were a bit patchier in the western parts of the Empire, but the idea of uniform economic decline isn't really tenable any more.

"Nor is our economic growth is not stuttering" has one more negation than you intendedThe "meritocratic civil service, once a great source of strength, had let to a situation" let -> led

I'd not come across the Kipling poem before, very apposite! (Though weirdly formatted)