Arise, Sir Humphrey

Give Permanent Secretaries knighthoods again

When I joined the civil service in 2006, my Permanent Secretary rejoiced in the glorious name of Sir Brian Bender. Though less hirsute than his Blessed namesake,1 he did pose for the staff magazine cover with his foot on a chair, knee raised, slapping his thigh in a ‘Well met, Bob!’ pose. He may or may not have been a good Permanent Secretary - I was really too junior to tell.

Crucially, though, he was Sir Brian Bender, a reassuring reminder that the spirit of Sir Humphrey lived on. At that time, almost every Permanent Secretary was a knight or dame, with typically the odd Director General or similar also having ‘their K’.2

How different it is today! Of the 20 odd Ministerial Departments,3 only six of the Permanent Secretaries are currently a knight or a dame - and that includes Sir Chris Wormald, the Cabinet Secretary, as well as Dame Sarah Healey, at MHCLG, who received hers in yesterday’s King’s Birthday Honours list.4 Other honours are also given out far lessreadily.

Questions about whether civil servants should get honours ‘just for doing their job’ have been around for a long while, with reduction in the practice through the New Labour years, but - at least apparently - seeming to particularly ‘bite’ during the civil service reforms of the Coalition period.5 These reforms contained many positive elements, including a tightening of civil service pay, public sector pension reform,6 some more mixed reforms to terms and conditions and an approximately 20% reduction in numbers - all part of their impressive achievement of getting public sector spending under control.7

But did we have to take away their knighthoods? Funnily enough, the argument that it shouldn’t be for ‘just doing their job’ doesn’t seem to apply to arm’s length bodies, where the head of a number of major quangos tends to receive a knighthood or damehood almost automatically upon stepping down.

In reality, there is a strong argument that, for the most senior elements of the civil service, ‘just doing their job’ is indeed a sufficient sacrifice and commitment to public service that honours are justified.

The relationship between public and private sector pay is a complex one. At junior level, the public sector compares very well; however, at senior level, those at the very top earn considerably less than those at the top of private sector organisations. While it is not true that any civil servant can automatically walk into a private sector job paying three times as much, it is true that, with typical salaries of £150k - £200k, Permanent Secretaries are paid many times less than their equivalents leading large private sector organisations of similar size and budgets (and, in addition, do not have the stock and share elements of remuneration which typically make up a large part of senior executive pay at this level - more than making up for the public sector pension).

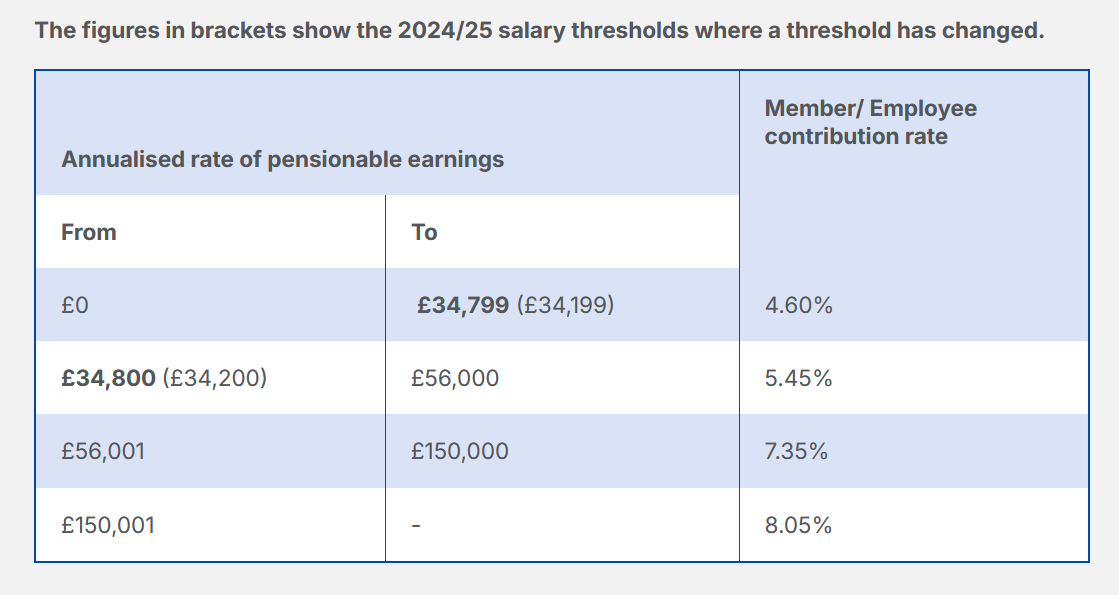

The civil service, almost uniquely, is one of the few organisations where your pension terms get worse as you get more senior.8 In the private sector, typically, either everyone gets the same or more senior executives get a better pension. In the civil service, high earners contribute more for the same pension.

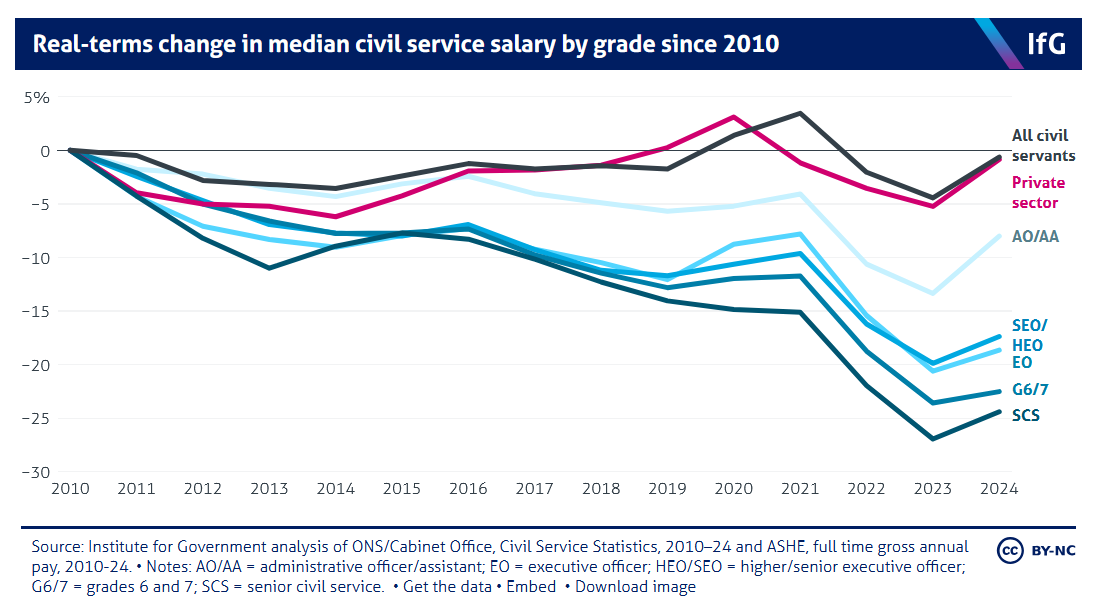

Senior Civil Service salaries have declined more than those of any other grade - by around a quarter in real terms since 2010. And while at intermediate grades, grade inflation has often compensated for this, at the most senior grade this clearly cannot happen. The Senior Salaries Review Body’s latest report, written with a degree of acerbity one rarely finds in these sort of formal documents, observes:

The issues noted and recommendations made in this Chapter arise from the same set of problems we have seen with the SCS over many years. Difficulties attracting sufficient high-quality applicants, high turnover and the lack of a simple pay progression system remain unaddressed. The lack of meaningful progress over an extended period to address this Review Body’s long-standing concerns is a source of considerable frustration.

The SCS pay system is broken. It does not work as it should to attract, retain and motivate a high-quality cadre to lead the government’s initiatives and oversee public services.

With the national debt close to 100% of GDP and interest payments on the national debt at over £100 billion a year - more than we spend on either defence or education - there are reasons why it is hard to give people a pay rise.9

In contrast, restoring their honours would be an easy and low cost way of improving a morale. It goes without saying that more knighthoods for Permanent Secretaries would not only increase the morale and attraction of the civil service for those receiving them, but also for the Directors General, Directors and Deputy Directors10 who hope to get them one day - particularly if they were accompanied with a greater smattering of the lesser honours amongst the senior ranks.11

Permanent Secretaries do a difficult job, leading large organisations with big budgets. By its nature, the job accrues far less personal public recognition than many others (this goes to the Ministers), and involves having to work on and lead policies they personally find objectionable.12 Their monetary remuneration is only a small fraction of what they could have earned outside - and as the Pay Review Body observes, this is having an impact, in terms of both attracting and retaining talent in the highest echelons. Regularly awarding knighthoods again - and other honours where appropriate - is the least we could do to make the package more appealing.

And anyway, wouldn’t there something conforting, dignified and altogether more British to know that each our government departments were once again under the steady hand of a knight (or dame) of the realm?

And less bad than his Botanical namesake.

As Bernard tells us, once, if one achieved certain positions, ‘one’s K was assured’.

I.e. excluding arm’s length bodies such as Ofsted, where the head is also considered of Permanent Secretary grade but not called a Permanent Secretary.

Some - but by no means all - do appear to receive them after retiring.

It is possible that it actually ‘bit’ earlier, but some people who’d formerly received them were still around.

Even though this was the one time I went on strike (in particular for the retrospective alteration of the inflation index used, which struck me as much more unfair than changing future terms), I have to concede that overall it was necessary.

Total Managed Expenditure fell by a whopping 5 percentage points as a share of GDP.

Though are still very good.

Though the SCS cadre is small enough that one could, actually, afford to do that. But then that might decrease morale in groups not receiving a pay rise.

Undersecretaries, Deputy Secretaries and Assistant Secretaries in old money.

I would be lying if I said the dramatic reduction in honours being given out was a major reason why I left the civil service. But I’d also be lying if I said it was entirely irrelevant.

A near certainty in any lengthy senior civil service career.

This misses the point for three reasons:

1/ This just reflects the point that the current cadre of Perm Secs is quite new. Around 12 months ago, half of perm secs had their Ks. Sir Jim Harra (HMRC), Sir Philip Barton (FCDO), Sir Crawford Falconer (DBT), Sir Alex Chisholm have all just left.

2/ EVERY Perm Sec who took up their place before 2020 (Ian Diamond, Bernadette Kelly, Peter Schofield, Chris Witty and Tamara Finkelstein and Ken McCullum) has a DBE or a K.

3/ The rule is that Permanent Secretaries get their Ks after 4 years in the job. In the old days, they weren’t on fixed term contracts. So this isn’t about perm secs not getting Ks, but about greater turnover at Perm Sec level.

I'm afraid you've committed the cardinal sin of confusing deficit and debt.