Reeves in Zugzwang

Incremental politics no longer works

The decision to means-test Winter Fuel Allowance remains one of the most politically damaging that this Government made. It was deeply unpopular, terminated their honeymoon period1 and continually appeared in polls as the single action most people were aware of. Ultimately the Government u-turned, eliminating most of the savings - and yet the Winter Fuel Allowance cut is still appearing spontaneously in focus groups. And all for a piddling £1.3 billion.2

Though not of the same political magnitude, we can find a parallel in to how Rishi Sunak tried to reform childcare. After pressure from charities, he chose to go for relatively modest reforms, marginally increasing ratios3 and removing a small amount of regulatory burden. Yet he was relentlessly attacked by children’s charities for endangering the lives of children, weakening safety standards and creating a ‘two tier’ system in which poorer children would have substandard provision. Unsurprisingly, the minor regulatory changes had little effect, and childcare remains highly expensive and in some cases unavailable.4

In both cases, heavy opprobrium was incurred for minimal real-world gains.

I intend to write a longer piece about political triangulation. But in short, it tends to work best when both sides get something they want - such as Blair’s ‘Tough on Crime, Tough on the Causes of Crime’ or - less well sloganised - Cameron’s combinations of fiscal responsibility and gay marriage.

Making small changes that leave all sides unhappy just doesn’t cut the mustard. And to be clear, that’s not just in a political sense.5 A bigger issue is that it’s not sufficient to actually solve the problem: it sticks around, continuing to be a problem.

And yet this incremental approach, of small, triangulated changes, that displease all sides without doing enough to solve something, has dominated the premierships of both Sunak and Starmer - two intelligent decent, honest men who have nevertheless rapidly become two of our most unpopular Prime Ministers ever.

Go big or go home

What if, instead, they’d put their money where their mouth was? What if Sunak had doubled the ratios for 2 year olds to 1:8 and removed them entirely for 3s and over - as is the case in France? What if he’d ended all Ofsted inspections of childminders, requiring them only to have the same DBS checks6 that football coaches or scout leaders do - and reduced inspections of nurseries to safeguarding considerations only? Let parents decide who they trust to look after their children, as we used to.

Well, the children’s charities would have screamed blue murder - but they did that anyway, so may as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb. And these reforms would have actually made a difference: new childminders opening up, freed of the burden of Ofsted; nurseries lowering prices, childcare becoming more available, flexible and affordable. One of the biggest costs in many parents’ lives coming down - significantly.7

That’s the sort of real difference in people’s lives that carries more weight than a one-off political row.

Or take Winter Fuel Allowance. Let’s begin the premise that Reeves has decided - entirely reasonably - to make pensioners bear some of the costs of balancing the books. What if, instead of only means-testing Winter Fuel Allowance, she means-tested every pensioner benefit, including free prescriptions - and then broke the triple-lock by freezing the state pension for three years, and thereafter increasing it in line with CPI inflation. That would net a cool £26 billion.

Unthinkable, you say? But why? What do you think would have happened?

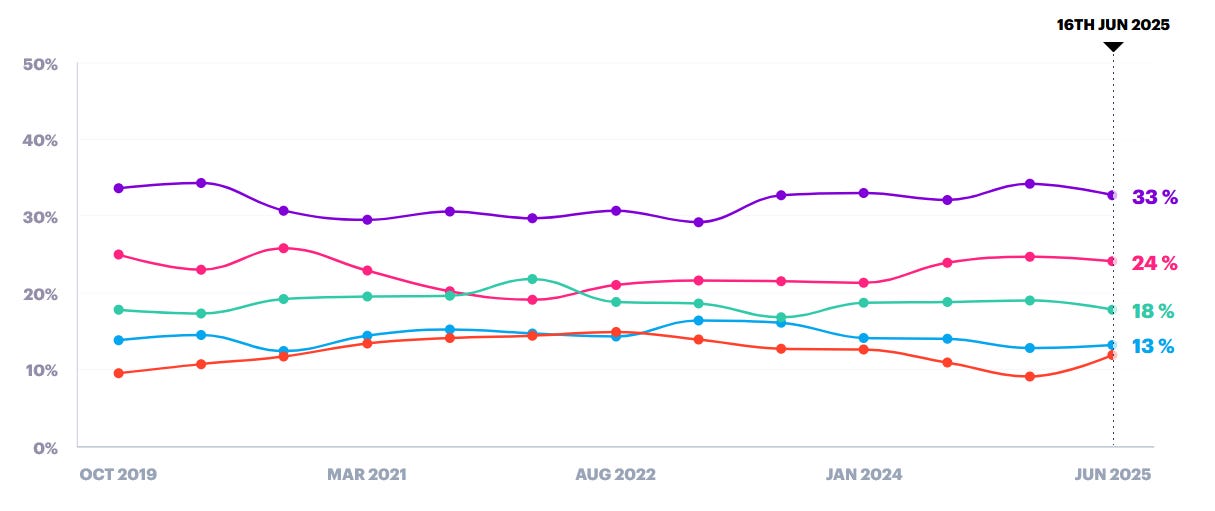

Labour is currently polling on 12% amongst the over 65s.8 I guess that number could go even lower - though at this point, you have to figure a good chunk of that 12% are die-hard Labour voters, who will stick with them through thick and thin. And some other people might have got angry with them, as they did with the Winter Fuel Allowance.

But on the hand, just think what they could have done with £26 billion. They could, for example, have lifted the two-child benefits cap (£3.5 billion) and abolished tuition fees (£8 billion) - two long-standing left-wing priorities - and still had almost £15 billion pounds left of fiscal headroom.9 They could have created millions - literally - of winners, to balance those who lost out.

Just as importantly, it would have allowed them to tell a story about why they were in Government and what they believed in. Instead of being the party of randomly being mean to old people, they would be the party of ending child poverty and lifting the burden of debt from the young, while asking some of those who have benefitted recently to take some of the strain. People - the public, their activists and their MPs - would have understood why the hard decisions were needed.

In addition to those who directly benefited, and their families, this would be a narrative that many others could also get behind. Perhaps even some of those who were losing out from the cuts would support it, feeling that they could afford it, and wanting a better life for their children and grandchildren.

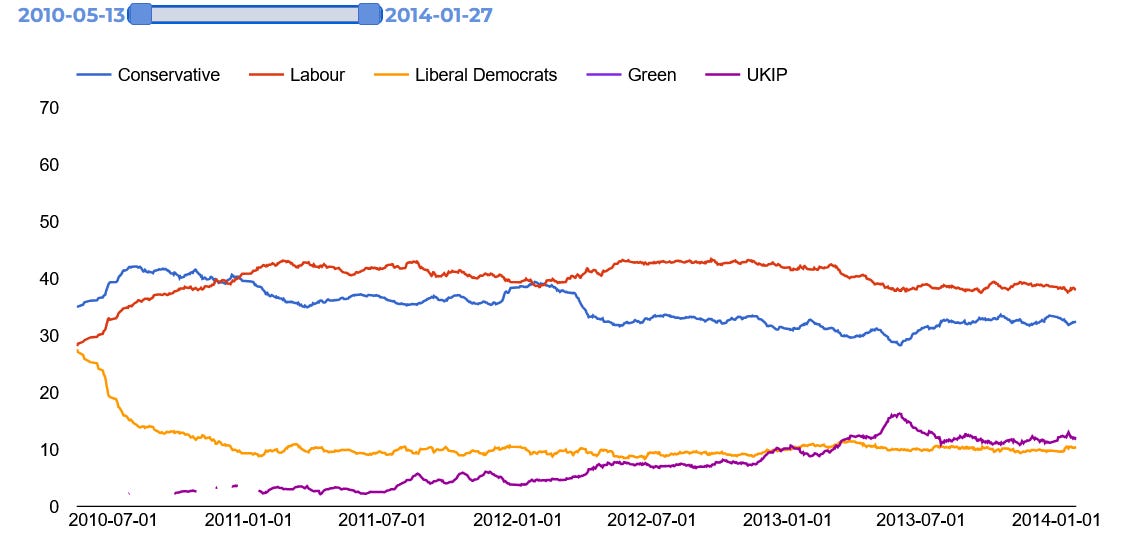

It doesn’t matter what’s popular the next day. Under Cameron, the Conservatives spent essentially the whole of 2012 and 2013 ten points behind - and yet won the next election with an increased voteshare.

What matters is whether you’ll be popular in five years, on the next polling day. And the only way that happens is if people understand how you’re trying to make the country better - and if the actions you take, however difficult at the time, actually deliver on that promise.

Essential Caveats10

If something is working well, incremental approaches are fine. The UK’s science policy is broadly in good shape, so no revolution is needed. Given the success of English schools over the last fifteen years, it was sensible for the recent curriculum review - despite the hype with which it was launched - to conclude by making only small changes - ‘evolution, not revolution’, as the chair put it.11

Similarly, even if incremental changes aren’t enough, going big doesn’t guarantee success. Reversed folly is not necessarily wisdom.

One major error is to think that simply talking big is enough. The Rwanda plan is an archetypal example, designed to be so bold it would convince the public the Conservatives were serious about stopping the small boats. But when no-one was actually sent to Rwanda (because the Government was unwilling to pass a Bill that would explicitly secure the deportations against legal challenge)12 it instead became a symbol of Government impotence - while still alienating all those who opposed it on principle.

Even when one does act as well as talk, the action has to work and be effective. This criticism can potentially be levied at Reeves’ last Budget: after all, at the time many certainly felt that a Budget that raised spending by £70bn, taxes by £40bn and borrowing by £30bn was no small potatoes. The specific measures, however, were fatally flawed:

The sharp rise in employers’ national insurance - combined with the inflation-busting rise in minimum wage - hammered economic growth, on which her long-term plan depended.

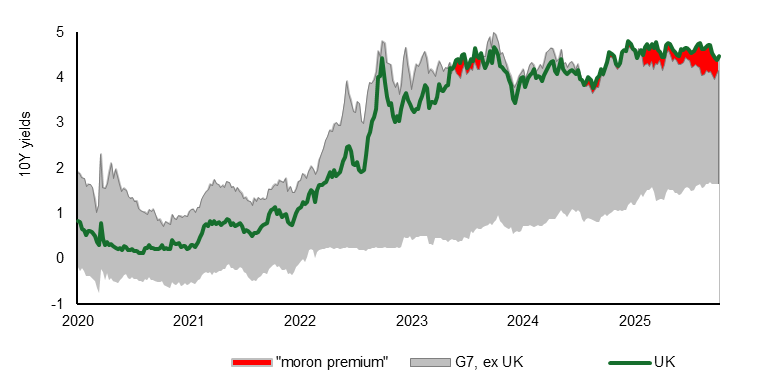

The big increase in borrowing caused interest rates to increase, increasing spending on Government debt and creating a vicious cycle of more borrowing.13

Much of the increased spending went not on investment, but on welfare and public sector pay increases, with the Government accepting union demands without conditions. Unsurprisingly, this has not secured long-term benefits: public sector productivity continues to fall, and the unions are gearing up for a new wave of strikes.14

So what does this mean for the Budget?

Reeves is in zugswang15 - caught in a cleft stick where there are no good choices left.

Her back-benchers will not allow her to cut spending.16 The bond markets will not allow her to borrow more. She has two choices: either to make a wide range of small, tax increases, or to break the manifesto pledge and raise income tax.

The first option, though it seems easier, is likely to be economically more harmful: the last think the UK tax system needs is more complexity, and most of the tax rises she could make - outside of the big ones of income tax, national insurance or VAT - will either not raise very much, or directly hit businesses and economic growth. They’re not going to be politically easy either:

Raising income tax rates, on the other hand, would be a direct violation of a manifesto pledge in the most visible way possible. For many higher-earning ‘values’ voters, who either voted for Labour (or were relaxed enough about them getting in to vote Lib Dem), £50-£100 a month extra tax coming out of their pay check each month would be a sharp reality check.17 In the Financial Times, David Sheppard argues compellingly:

“Freezing tax bands, higher council taxes, capital gains exit taxes, higher gambling taxes and other measures can, when combined, get Reeves within touching distance of her goal. All of these are painful for a chancellor to push through, and could still tarnish the government — and the broader economy.

But none of them carry the irrevocable taint of going back on the pledge not to raise income tax, VAT or National Insurance. Doing so would not just be political suicide for Reeves, but quite possibly for this government too.

No matter how much Reeves dresses the move up as acting in the national interest, she will be pilloried by the press. It was not just a throwaway comment, but a central pledge in the party’s offer to voters. You might think it was an ill-judged promise that should never have been made in the first place. But make it they did.”

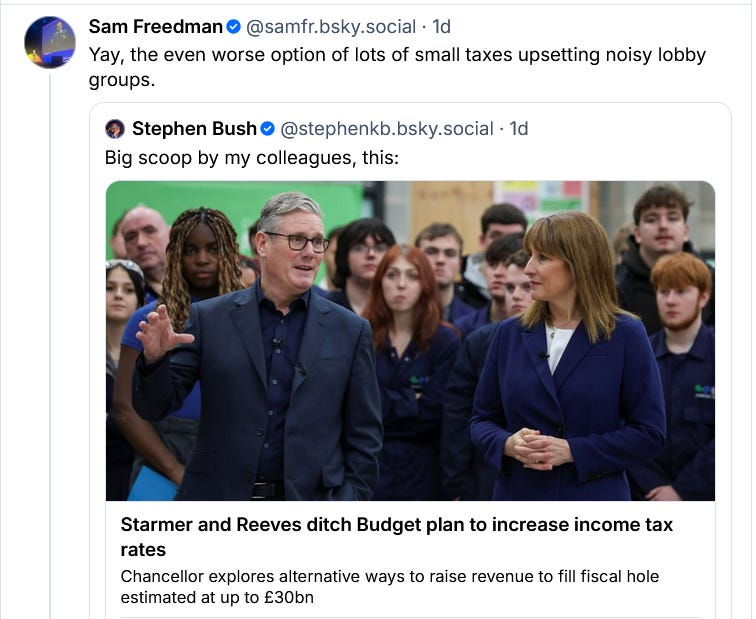

Based on briefing from the last couple of days, despite pitch-rolling an income tax rise for some weeks, it now appears that Reeves (and Starmer) agree with this analysis, and that rises in income tax rates are off the table. Instead we will get a further freeze in thresholds, alongside the host of minor measures.

The irony is that there would have been a time when Reeves could have got away with raising taxes - and that is last Budget.18 Spend the summer pitch-rolling, talk about the ‘black hole’ and how it was ‘much worse than they thought’. Don’t queer the pitch by announcing Winter Fuel Allowance cuts in July, but instead roll that - alongside other savings from the elderly - into the Budget, as part of a message ‘that we all need to do our bit’. People wouldn’t have loved it - but they might have accepted it.

As to the long-term impact, there’s a mainstream view on the centre-left,19 that the way to get Britain growing again is to tax and spend more. If only we spent more on back-to-work schemes, on proactive interventions on mental health and sickness, on education, on youth work, on investment in transport and energy, then our economy would revive.

As you might expect of someone on the right, I’m pretty sceptical of this,20 and even more sceptical our Government could pull it off, rather than blowing the money on benefits, pensions and unions. But unlike Modern Monetary Theory or the belief that tariffs cut inflation, it’s a mainstream theory, which plenty of smart people believe, and that doesn’t violate the laws of economics. Carrying out that sort of intervention in her first Budget - raising the needed funds and spending it decisively on the correct things - would have given it the best chance to succeed. And maybe she could have taken the country - and the Labour Parliamentary Party - with her.

But now? Both Starmer and Reeves are deeply unpopular, with net approval ratings at, respectively, -56 and -52. I’ve worked for a minister with approval ratings in this territory and it is nigh on impossible to shift them. Even if one announces a popular policy, the very act of their name being associated with it makes it unpopular.21 The public effectively have trapped priors, leaving the politician in a form of shoe-shop event horizon where no matter what they say or do, it makes them more unpopular.

So what should Reeves do?

This is a difficult question to answer. What I think the Chancellor should do is very different from what Reeves thinks.22 And even what Reeves thinks is needed is very different from what her back-benchers will let her do. So to answer ‘should’ becomes a kind of ideological Turing test under political constraints.

But if I were advising Reeves right now, I’d urge her to go big. Risk it all on one last roll of the dice: raise income tax, end the triple lock, slay the deficit, spend the money on the things you believe in.

Of course, it is likely enough that this would result in them going to their doom. But if she plays it safe and does nothing, doom would find them anyway, sooner or later.23

It may or may not help them get re-elected. But she only needs 30% to win24, and it would have more chance than sticking on the current path. And even if it didn’t, at least she could get done some of the things she believes are right for the country.

When every move causes you to lose, sometimes you have to flip over the table.

But ultimately, whatever is in the Budget, it is likely to be too little, too late.

Along with the ‘cash for clothes’ scandal.

I appreciate that I would not consider £1.3 billion to be piddling if it appeared in my bank account. But it’s 0.1% of total public sector spending (£1,300 billion) and about 1% of what we paid on debt interest last year (£111 billion).

To the same level as that uncivilised and barbarous country…Scotland.

The highly restrictive regulations also hampered the implementation of his £4 billion pound extension of ‘free’ childcare, with many providers simply compensating by increasing the costs of the non-free provision.

Though it is also very much in a political sense.

I.e. to ensure they are not paedophiles.

There is an argument that Sunak just didn’t have enough time for the benefits to take place before the election. But you could argue that about almost anything - and it would still have had the positive real-world effects.

I am using More in Common’s data tables here, because they were (a) one of the more accurate in the last general election, and (b) their latest poll has Labour on 18%, the same figure as the Politico Poll of Polls.

Don’t get too hung up on these specific examples. These are two things I often see those on the left calling for, but if you think that Reeves should or would have spent it on some other Labour priorities, that doesn’t affect the core argument.

Would you expect anything else from this blog?

Though better yet not to have a review at all.

To quote Yuan Yi Zhu, “It is hard to understand the logic of this approach. Are there really many swing voters in the country who would be scandalized by the disapplication of section 4 of the HRA but who are fine with the disapplication of section 3?”

UK interest rates have been steadily moving above comparator countries:

There is a long political tradition of giving this sort of unconditional bung to one’s supporters - but the standard way is to do so shortly before an election, not immediately after winning one.

A chess term referring to a position in which every possible move makes your position worse.

Last month the Government formally abandoned any plans of making savings from their ongoing benefits review.

Under the rumoured - now abandoned - plan, by also cutting 2p from National Insurance, those earning under £50,000 and below state pension age would not pay more.

Though it would help if the summer hadn’t been spent on frock-gate and rows about Sue Gray.

Espoused, for example, by the Resolution Foundation, or by Sam Freedman in his book Failed State.

Except for the investment in transport and energy. And even there we’d have to do it, not sink hundreds of millions and many years into the planning process - for the Lower Thames Crossing we’ve spent around £300m in the planning process alone.

An example would be ID cards, where years of consistent net support (see below) for the policy collapsed to net -3 opposed, after Starmer announced his Government would be bringing them in.

.

I would prioritise significant cuts to public spending to reduce the deficit, and ultimately lower the burden of taxation, alongside major regulatory and planning reform.

You may object to this advice on the grounds that Rachel Reeves is not an immensely strong talking tree. But then neither is Nigel Farage an immortal divine being with magical powers.

If Labour and Reform are both on 30%, Starmer stays as Prime Minister, even if only as head of a coalition / minority Government.

Great analysis

24 foot notes but not one for the wonderful "Shoe shop event horizon".

Budget is day before thanksgiving with Financial Markets pretty much closed for 5 days after. Bar Christmas eve worst day in year to hold it. If they cant even choose a sensible day to hold a budget I doubt they can produce a good budget.

I was also thinking recently what I would do if I were Rachel Reeves and came to a similar conclusion:

• Increase both the basic and top rate of income tax by 5p

• Use the extra revenue to cut or scrap various other taxes, invest in infrastructure, and reduce the national debt. Only increase public spending in areas where it seems likely to have a significant economic or political benefit.

• Scrap the pensions triple lock and the de facto minimum wage triple lock

• Bold deregulation, as much as I could possibly get away with, especially in planning

• Try and find public spending cuts that are not too unpopular among Labour MPs and voters

My reasoning was the same as yours: Labour is doomed anyway if they do nothing and everything is just a bit worse by the time the next election rolls around, with no economic growth and no achievements to boast about.