On the Stupidity of Carer's Allowance

Infinite marginal tax rates are a bad idea, actually

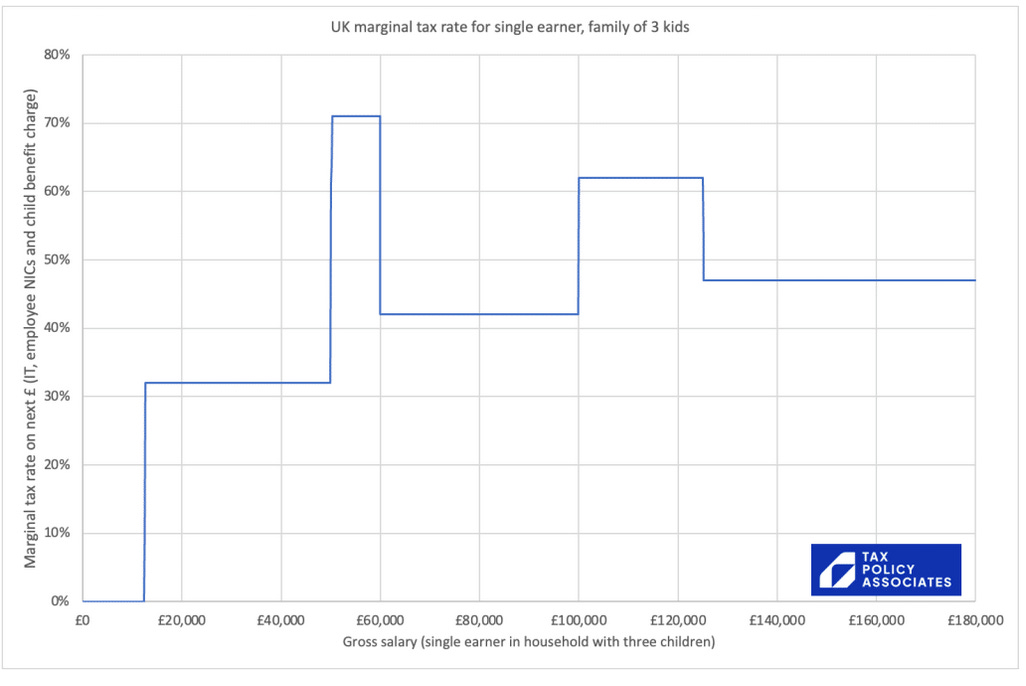

Regular readers will know that the UK’s income tax system is highly distorted. Rather than being a straight-forward progressive system, in which richer people face higher marginal rates of taxation, it instead features multiple peaks and valleys, as shown in the ‘skyline’ diagram below.1

As the saying goes, you may legitimately think the top rate of tax should be 62%, or 47%, or some other number entirely. But it makes no sense whatsover to think that people earning £100k to £125k should pay 62%, and those earning over £125k should only pay 47%.

Even worse than this, however, are the points where the marginal tax rate becomes infinite - such that earning more money leaves you actually worse off.

One of these that is talked of frequently is the removal of childcare support at £100,000. For a family with two children under 5 receiving ‘free’ child care, if one parent goes from £99,999 to £100,000 they will immediately be around £20k worse off. Their net pay won’t recover until they’re earning around £145k - meaning that it is logical to turn down pay rises of 20, 30 or even 40 grand.2 The only silver lining is that at least children don’t say under 5 for ever, meaning most parents aren’t trapped here for too long.

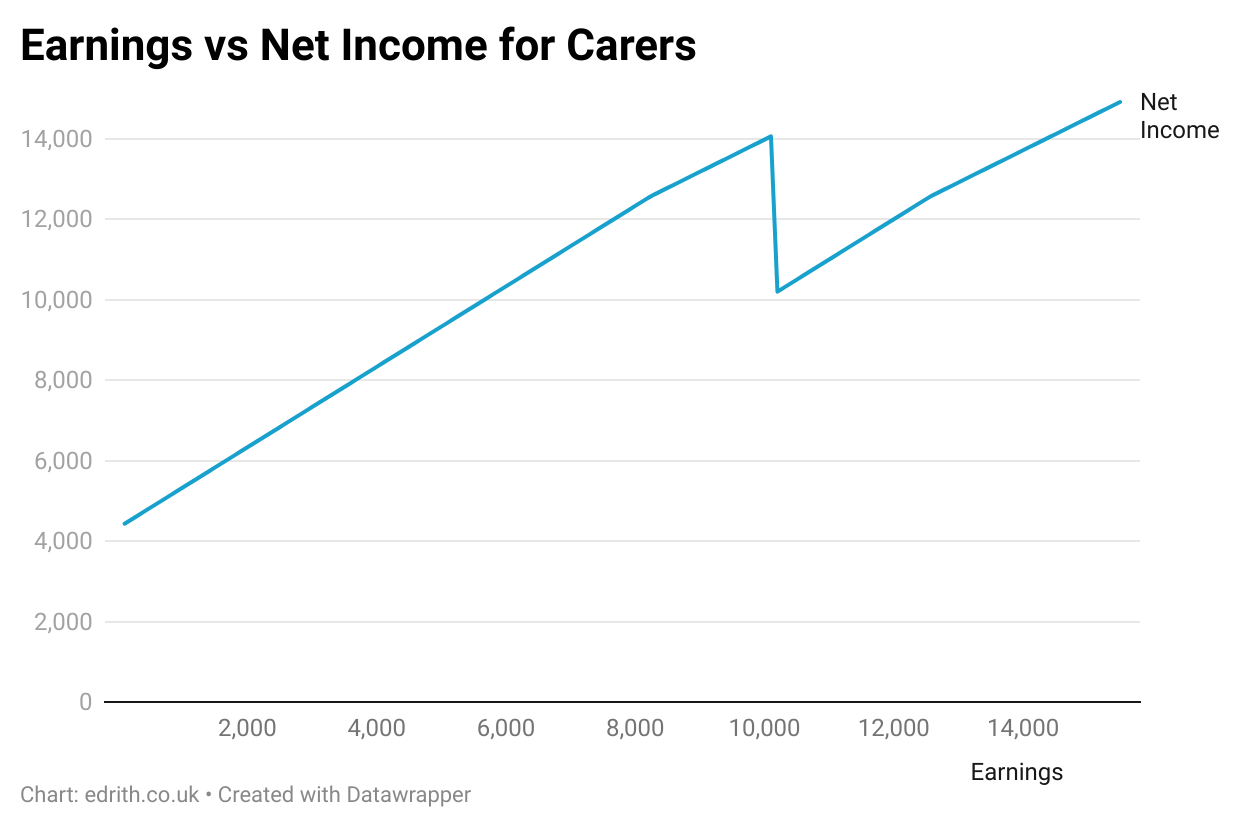

Another infinite marginal tax threshold that is spoken of far less often - probably because fewer MPs or senior journalists are affected - involves Carer’s Allowance: a benefit worth just over £4,000 a year, and that one loses, entirely if one earns on average over £196 a week (or just over £10,000 a year). That works out as 16 hours a week for someone on minimum wage.

To be precise, someone earning £10,100, who received a pay rise of just £100, would suddenly find themselves almost £4,000 worse off. They’d have to get a pay rise of over £4,300 - over 350 more hours, at minimum wage - just to break even: anything less, would be a net loss.

What is Carer’s Allowance?

Carer’s Allowance is a benefit that can be claimed by people who are caring for another person for at least 35 hours a week, if that person is in receipt of certain specific benefits such as Disability Living Allowance, Personal Independence Payments, Pension Age Disability Allowance, and others.

You have to be 16 or over, you can’t be in full time education and, crucially, you have to be earning under £196 a week.

If you receive it, you get a flat rate of £83.30 a week, or about £4,300 a year.

It’s claimed by just over 1.4 million people a year3 and therefore costs a total of £6 billion a year: this is not a fringe benefit, but one that impacts a large number of people and costs a fair chunk of money.

All of which means it’s worth thinking about how its design is distorting behaviour in ways which helps neither the individuals receiving it, nor society as a whole.

The infinite marginal tax trap

One reason why I know about Carer’s Allowance is that my wife has been claiming it since 2019,4 when she had to stop paid work to care for Youngest, who had and has some serious health difficulties. Over the last couple of years, as Youngest’s situation has become more stable, she’s been able to take up some work again - and as a result, we’ve become intimately familiar with the eligiblity rules.

I should say here, that I feel we are very fortunate to receive this, especially given that other benefits are means-tested. Given the current fiscal situation, where the UK is paying £111 billion a year in debt interest alone, it would be entirely reasonable for the Government to means-test this for higher earning households like ours, as it does with child benefit.5

What is more, for those in our situation, as I’ll set out below, the income eligibility threshold is fairly easy to manage. But most carers aren’t in this fortunate situation - and as someone with an audience in the policy making community, by writing about it I can raise awareness of this under-discussed income trap.

Because it turns out that if you happen to be a highly skilled, self-employed carer, who can command a high hourly wage and isn’t the household’s primary earner, then it’s not so hard to keep your average earnings £196 a week.

If you’re self-employed, you can often flex work from one financial year to the next - particularly if you work in education, when the academic year doesn’t line up with the financial year. The Government allows you to offset resources and business costs against earnings - and again, you probably have some choice on when you purchase these. And if worst comes to the worst, you can make pension contributions, and offset 50% of these against the limit - which is not a problem if you’re not the principal household earner.

What’s more, as a relatively high earner, if my wife did choose to move over the threshold, it would be relatively easy for her to go from £10k to £20k, making the loss of carer’s more like a high marginal rate, rather than actually losing money.6 The fact that the eligibility is based on income, rather than hours worked, gives high earners a major advantage.

But most carers aren’t in this situation

But guess who can’t do any of these things?

Most carers, that’s who. Most carers who aren’t self employed, aren’t high potential earners7 - and whose households may be much more dependent on their income.

If you’re working a normal part-time job, then you can’t always work more or less, and you probably don’t have expenses you can move from one year to another. But a single over-time shift could bump you over the threshold - costing you over £4,000 for the ‘sin’ of working a few extra hours.

This isn’t just about the impact on individuals, either. As a society, it’s better if we can get more people and households supporting themselves through their own work and income, not dependent on the state. Most people8 want this too. But the current structure of Carer’s Allowance actively works against this.

Let’s take someone on the median part-time hourly wage of £13.26 - and let’s say they’re working 12 hours a week, which they could do while still receiving Carer’s Allowance. Their total income - assuming no other benefits would be £8,274 from work and a further £4,331 from Carer’s Allowance, for a total of £12,605.9

The opportunity comes up for them to take on an extra 4 hour shift at work each week - and they believe that the person they are caring for is now able enough that they could do this. But, if they take this up, they’ll lose the entirety of Carer’s Allowance - meaning that although their earnings would go up to £11,032, that would be all they’d get - meaning that taking on that extra weekly shift would actually decrease their total income by £1,573.

Who’d work more hours at the same job for less money?

For someone on the median part-time hourly wage, they would have to work an extra 326 hours a year - or more than 6 extra hours a week - to just break even if it pushes them over the threshold.

So, how to fix it?

A year or two ago, Carer’s Allowance was in the news because the Government was pursuing people who had - often accidentally - claimed it when they were over the earnings limit, and now were being asked to pay it back.10 In many cases, these were people with not very much money at all, who had sometimes only exceeded the limit by a small amount and who were now being asked for relatively large sums of money - in some cases, more than the amount they’d gained by earnings.

I was hopeful that this would lead the Government to fixing it. But instead, they just raised the threshold by about 1/3. This helped a bunch of people to earn more11, but it did nothing to resolve the fundamental distortion that instant, full withdrawal causes - it just moved the cliff-edge to a different place.

It was a wasted opportunity for proper reform.

Clearly there needs to be some way of withdrawing Carer’s Allowance as people earn more.

It’s meant to be for people who are, effectively, full-time carers, spending 35 hours a week on caring - so we don’t want to give it to people with full time jobs. And, given the state of public finances, there are strong arguments to not give it to people who otherwise have a good income.

But an infinite marginal tax rate, where people can actually be significantly worse off for earning a small amount off, is one of the worst ways to do this - and causes unnecessary economic harm.

The simplest solution would be to have a taper: simply withdraw the benefit by 1 pound for every two pounds earned, instead of removing it all at once. Although this does still leave an effective marginal tax rate that is higher than ideal, high marginal tax rates are less distortionary than infinite marginal tax rates. Crucially, no-one would ever have less money because they earned more.12

The exact range over where it was tapered could be set to be fiscally neutral - i.e. it would neither cost nor save money.13 This would mean that the taper would start below the current threshold, meaning some people who are currently earning a little under that threshold14 would lose some money, but others who are currently earning over the threshold, would get some - though not all - of the benefit.

If one wanted to change it further, for example by starting the taper at a higher level, or tapering it more gradually, there are other options one could look at to make it more focused on those in most need. You could remove it from high-income households15; or from those with high levels of savings16, or from those who have a high income from a pension.17 Many other benefits are means-tested in one or more of these ways, so there would be precedents.

But ultimately, these are secondary. The most important reform needed is to remove the cliff-edge, which means people can be actually worse off by earning more - a cliff-edge which stops people who want to support themselves from doing so, increases reliance on the state and can mean some people - including some very low earners - can actually be worse off for earning more.

This looks even worse if you include student loan repayments. And if one looks at benefit withdrawal rates, there are some appallingly high effective marginal tax rates.

You might say why should we care about people earning over £100,000. But actually, plenty of people who contribute a lot to our society - from doctors to computer programmers - fall into this category, and they can often adjust their earnings to stay below it, for example by going down to 4 days a week. In which case society loses both the fruits of their labour and the extra tax they would have been paying.

Coincidentally, this is almost exactly the same as the number of people earning over £100,000 a year - who are potentially impacted by the other infinite marginal tax threshold.

And she has given me permission to write about this.

Though that does of course result in unfortunate marginal tax rates elsewhere. Though usually not infinite ones.

But what about continuing to care for 35 hours a week? Without going into specific details, her rate is sufficiently good that she could be a higher rate tax payer and still working fewer than the 16 hours a week that the threshold would permit a minimum wage earner to do.

I don’t have specific evidence about carers here. But most people in the country aren’t high earners, and far more people are employed than self-employed.

Though not all.

Technically speaking they have to pay tax on the amount above the threshold, but given they’re only £45 above the personal allowance we’ll ignore that.

As it happens, I was on Newsnight at one point, discussing it alongside Ed Davey and others.

Including us.

To fully solve this, it would need to be stitched together with the tapering for other benefits, such as Universal Credit, for those Carers who are also in receipt of those other benefits. But even if one didn’t do that, it would still be a straight improvement over the status quo.

In general I am a strong believer in tax and benefit changes that are being made ostensibly for economic efficiency reasons, or for public health or climate reasons, to be fiscally neutral. As otherwise it’s likely the proposer has an ulterior motive.

Including us.

Such as ours.

Also such as ours.

Eligibility for Carer’s Allowance is weirdly unbothered about income and wealth, only about earnings.

I mean, I agree, and it should not be a complicated principle to say that cliff-edges are bad and economically distorting.

I suppose though the counter argument is that a taper becomes a highly complex administrative burden, particularly where earnings are inconsistent, which is very likely to be the case. A fairly likely scenario is, for instance, cleaning jobs (self-employed), or flexible retail or caring (I know multiple families where the mother puts in a full day caring for a family member and then works the overnight shift in a carehome or private care arrangement - again self employed - or does an evening shelf stacking, while the father is home from a 9-5 (ish) job to take over caring duties). You might get a shift for a couple of weeks while someone else is on holiday, or do some one-offs at a new house, or holiday let changeovers in the summer, then drop it again. Trackable if it's via PAYE to ease the taper but not so easy if it's self employed. (Clearly not impossible, but more for everyone to do, track, check up on and get wrong.)

Footnote 2 deserves a full post of its own. If this government is serious about growth and productivity, it’s worth shining a spotlight on silly policies that disincentivise those things.