Guest Post: “The Late Lord”: John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, and the formation of a historical reputation

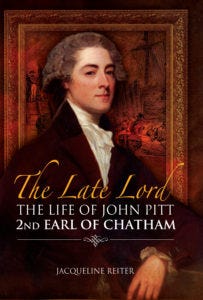

This is a guest post by Dr. Jacqueline Reiter about her book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham (Pen and Sword, 2017).

About 18 months ago I published my first biography, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham. It’s rare to find a historical figure of any stature who hasn’t been “done” before, but the 2nd Earl of Chatham is a special case. The more I researched him, the more I realised he was an excellent vehicle for investigating the well-trodden paths of Napoleonic political and military history from a fresh angle.

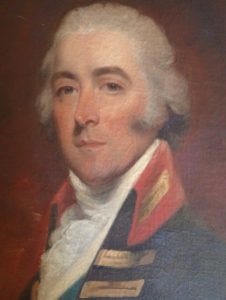

Chatham is rarely remembered positively. The longest assessment of his career until my biography appeared called him “a haughty, proud man … vain, pompous, [and] stupid”, and most historians agree.[1] I do not, but it is not hard to see why Chatham’s reputation is so poor. He was thoroughly overshadowed by his far more famous relatives – his father, William Pitt the Elder, and his brother, William Pitt the Younger. He was also notoriously lazy. He rarely got up before noon, as is well-attested in the manuscript sources, and this led to the nickname that gave me a title for my biography: “the late Lord Chatham” (an epithet bestowed on him about 40 years before his death in 1835).

His laziness would have mattered less had he been successful, but he was not. A military man who rose to be a full general in the British Army, his record in the field was abysmal (this in the age of Nelson and Wellington, of the Nile, Trafalgar, the Peninsular War, and Waterloo). He became particularly infamous for commanding the Walcheren expedition of 1809, an expedition marred by bad planning, bad leadership, and appalling human tragedy.

Evacuation of Walcheren by the British, 30 August 1809, by H.F.E. Philippoteaux, Wikimedia Commons]

The army under Chatham’s command was the most ambitious expeditionary force the British had undertaken up to that point (bigger even than Wellington’s army in the Peninsula); 40,000 soldiers and more than 600 naval vessels were sent to capture the Dutch island of Walcheren and destroy the French fleet and dockyards at Antwerp. Although Chatham managed to take Walcheren, he advanced too slowly, allowing the French to reinforce Antwerp. By the time he suspended operations, a quarter of Chatham’s army had been struck down with “Walcheren fever” (a combination of diseases, including malaria). One in ten soldiers who served in the expedition died, and the illness returned periodically to weaken the survivors for years to come.

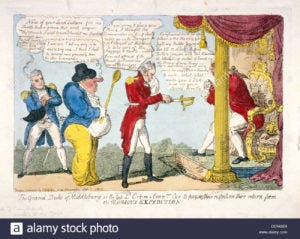

One of the many satires on Chatham following the Walcheren disaster; public domain, from alamy.com

Walcheren destroyed Chatham’s reputation completely. A political inquiry followed the disaster; although Chatham was largely cleared of incompetence, his political colleagues refused to stand by him and he was forced to resign his office as Master-General of the Ordnance. He spent the rest of his life in the wilderness; even his contemporaries forgot him. When he died, diarist Charles Greville wrote, “Lord Chatham died the day before yesterday, which is of no other importance than that of giving some honours and emoluments [to the prime minister] to distribute.”[2]

As I wrote in my biography, “Greville’s catty epitaph also bristled with irony: having dismissed Chatham as a nonentity, he had nonetheless felt his death important enough to record.”[3] The more I read about Chatham, the more I realised his whole life was shot through by these kinds of contradictions. He may have been a failure, but he was a failure with much to teach us about the way British political and military life worked at the turn of the nineteenth century. Few historians have bothered to look at Chatham beyond Walcheren: yet Walcheren took up only 11 months of Chatham’s life. They might be the most important 11 months of his life, but looking at Chatham solely through the lens of military failure obscures his importance in other spheres.

Chatham had several overlapping identities. He was not only a soldier: he was also a politician, a courtier, and an aristocrat, and each gave him a sphere of influence independent of his connections as a Pitt and as the son and brother of prime ministers (although this obviously did not hurt). His friends and correspondents included members of the Royal Family, high-ranking army officers, and prominent members of the political establishment. Crucially, he occupied a central role in government at a critical time in British history. He was a wartime First Lord of the Admiralty and Master-General of the Ordnance, two highly important cabinet posts with military responsibilities. He was close to the prime minister and to the King (George III openly professed “the warmest affection” for him[4]), and he was one of the only cabinet ministers to serve militarily while in office. As such, his opinion carried considerable weight in discussions on strategy. Nor did his closeness to Pitt the Younger make him a “yes man”. He and his brother often clashed on domestic and military matters, including peace with France, abolition of the slave trade, Catholic emancipation, and the war in the Mediterranean. Later, Chatham caused trouble for his colleagues on important matters such as the 1807 bombardment of Copenhagen or sending an army to Spain.

A gun bearing Chatham’s cipher as Master-General of the Ordnance from the Tower of London. Photograph by Jacqueline Reiter.

All this made Chatham a prickly colleague. One fellow cabinet member refused to be in the same room as him after an argument[5]; another described Chatham as “a great frondeur”[6], or troublemaker. Particularly after Pitt’s death in 1806, however, no government formed on an explicitly “Pittite” basis could afford to leave him out. Chatham very nearly followed in the footsteps of his father and brother to become prime minister himself. Only unfavourable private circumstances and, eventually, military disgrace prevented him taking up the post.

As proficient as he was at making enemies, it is worth mentioning that Chatham was surprisingly good at inspiring a touching degree of loyalty and affection. One man who served with him for over 10 years described him – after Walcheren – in the following terms: “The more I see of him, the more I am convinced that it in understanding few equal him, and in honour and integrity he cannot be excelled.”[7] Part of this may have been sympathy for fallen greatness, and Chatham had more than his fair share of personal tragedy in his life, but it is still an amazing tribute from someone who had worked closely with Chatham and knew him well, and shows a side of Chatham’s character that has never really come to light before.

I cannot fully overturn preconceptions about Lord Chatham, who deserves his poor reputation as a general, even if his societal and political importance has never been recognised. I do, however, hope I have shown that reinserting Chatham into the historical narrative involves important reinterpretation of British political and military events during the Napoleonic Wars. I especially hope I have contributed to helping people view Chatham less as a figure of ridicule or contempt, and more as a serious personality in his own right. One of his colleagues, Lord Eldon, famously called him the ablest man in the cabinet; but Eldon’s other, equally perceptive, assessment is less well known: “Being the first-born of [his] illustrious father, and the inheritor of his honours … as it too often happens with persons in similar circumstances, his understanding and talents had not been as assiduously cultivated as those of William Pitt.”[8] Chatham could never have hoped to match either of his more famous relatives, either in fame or in achievements; but he did try, and for that, I think, he deserves some recognition.

References

[1] Sir Tresham Lever, The House of Pitt (London, 1947), pp. 360–2.

[2] Henry Reeve (ed), The Greville Memoirs, 3 vols (London, 1875), vol 3, p. 323.

[3] Jacqueline Reiter, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham (Barnsley, 2017), p. 209.

[4] George Pellew, Life of Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, 3 vols (London,, 1847), vol 1, p. 299.

[5] Lord Hawkesbury to the Duke of Portland, 2 March 1808, University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections PwF 5.849.

[6] Lord Bathurst to Lord Camden, undated, Kent Archives U840/C224/3.

[7] Thomas Carey to William Huskisson, 3 May 1810, British Library Add Ms 38738 f. 26.

[8] Horace Twiss, The life of Lord Eldon, 3 vols (London, 1844), vol 2, pp. 559-60.

About Jacqueline Reiter

Jacqueline Reiter has a PhD in late 18th century history from the University of Cambridge. Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham (Pen and Sword, 2017), was described as “well written, entertaining and perceptive … a model biography” by Rory Muir (author of Wellington: the Path to Victory and Wellington: Waterloo and the Fortunes of Peace), and “charming and hugely impressive as a feat of scholarship” by John Bew (author of Castlereagh: Enlightenment, War and Tyranny). Her articles have appeared in History Today and in the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research; she is currently co-writing a chapter with John Bew for the forthcoming Cambridge History of the Napoleonic Wars. She lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/latelordchatham

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/latelordchatham/

Website: http://thelatelord.com