An Arminian take on Public Services

Are libraries for everyone, or only for those who use them?

This post was voted for by paid subscribers for me to write about in the second quarter1- . While there is absolutely no need to ‘upgrade to paid’ as all content is free, a perk I offer to those who have very generously done so is the chance, each quarter, to vote on a topic I will write about that quarter, out of at least four choices. For those who would like to do so next quarter, I will be sending out the poll next week, so if you would like a vote, then now is your chance to subscribe. ‘Founding’ subscribers also get the additional option to propose topics to the quarterly poll.

So who was Arminius?

We’ll get there, but we’re going to start with John Calvin.

Other than owning a pet tiger and relocating the papacy to Geneva2, Calvin is perhaps best known for founding a branch of Protestantism known as Reformed Christianity or, more typically, Calvinism.

Calvinist theology is typically summed up in an acronym known as TULIP3: Total Depravity, Unconditional Election, Limited Atonement, Irresistable Grace and the Perseverance of the Saints. From this one can derive dourness, the Scots and the Protestant work ethic4.

Fun as would be to write about the Total Depravity of public services, the one we’re interested in today is Limited Atonement.

In standard Christian doctrine, Jesus died to atone for people’s sins. But not everyone, in fact, repents and follows Jesus; for everyone else, their sins are not forgiven. So did Christ die for everyone’s sins, or only for those who actually repent and follow him?

For Calvinists, Limited Atonement answers the question in favour the latter: Jesus’s death only atoned for those who actually follow him - the Elect.

Now, Arminius (told you we’d get there) was a Dutch theologian who disagreed with Calvin and, realising he’d been born a millennium and a half to late to defeat three Roman legions in the Teutoburg forest, turned his hand to theological debate instead. He disagreed with Calvin about lots of things5, including Limited Atonement and held that in dying, Jesus atoned for everyone’s sins, not only those who repent and follow Him. Sure, some people don’t take up that offer and so can’t be foregiven - but Christ still died for them, even if they reject them.

Hang on a minute, say the Calvinists, God is omnipotent and omniscient. He knows from the beginning who will turn to him and who won’t; in fact, He chooses the elect according whatever ineffable criteria He chooses6 and so the atonement is limited to them. Saying ‘in principle he atoned for the others as well’ doesn’t even make sense.

Arminians respond by saying that just because God knows who will turn to him and who won’t, that doesn’t take away their free will in making that choice. If you go back in time and watch someone making a choice, the fact you know in advance what they’ll choose doesn’t mean they’re not really making a choice. Grace enables each person to respond, if they choose to do so. So Atonement is indeed Unlimited.

Calvinists then point out that God is hardly just an observer, but determined all of the boundary conditions of the universe when He created it, so He really did predetermine everything and so Atonement is Limited to the Elect, by design.

At this point, the correct Arminian response is to shout, “Hah! Free will, losers!” and karate chop the Calvinist in the neck7, thereby ending the theological debate, at least for a time.

At this point we should end the theological introduction, both to conceal the fact that I am rapidly getting out of my depth and also because this post is meant to be about public services.

Didn’t you say this was something to do with libraries?

One can apply the same dichotomy to public services. Take any service that is freely available - such as a public library. Is that library there for everyone, or only for those who use it?

Let’s assume first that the library is genuinely open to everyone. It’s easily accessible, in the centre of town and has a wheelchair ramp. It doesn’t ban people wearing turbans, or have more subtle ‘unofficial’ dress codes such as turning away anyone who looks ‘scruffy’ or ‘unsavoury’. It has decent opening hours, including at weekends and at least one evening and is otherwise what you’d expect of a good public library8.

But still, some people are going to use it more than others. Some won’t use it at all. Is the library there for them? If there are 10,000 people in the town, and only 4,000 people use it in a year, is it a library that serves 10,000, or 4,000?

What if different ‘types’ of people are more or less likely to use it? What if 3/4 of middle-class people use it but only 1/4 of working class people? Is the library for middle class people more than for working people? What if women use it more than men? One ethnicity more than another?

An Arminian9 perspective would argue that the library is there for everyone. The state provides the library, yes, no-one can get to the library without the state providing it, but it is up to each individual’s free will as to whether or not they go. Regardless of that choice: the library is there for them.

A Calvinist would argue that the library is only there for those who use it. It is meaningless to say that it is ‘in some sense’ there for those who don’t use it; they don’t use it, and that’s that. If they don’t use it, they’re getting no benefit from it, so it’s ridiculous to say that the library is there for them.

In case you’re an Arminian thinking of pointing out that, unlike God, the state is not omniscient, the Calvinist will have a response for you. That may be true on an individual level, but as Hari Seldon showed, human beings, though impossible to predict on an individual basis, can be predicted reliably on a statistical basis. We know who’s going to use that library.

We have strong statistical evidence that, consistently, middle-class people use libraries more than poorer people do, so if you’re considering building a new library - or using sparse funds to keep one open - you know exactly what you’re doing. You’re spending public money predominantly on the wealthy, so don’t kid yourself with any of that Arminian, ‘technically it’s there for everyone.’ The benefit of that library is strictly limited, and it’s limited (mainly) to the middle classes.

It’s clear that this analysis doesn’t restrict itself to libraries, but can be extended to any free and universal public service. Are hospitals there for the sick and the healthy, or only the sick? Is debt advice there for the prudent as well as the feckless? If you’re well off enough to never need a foodbank is it still, in some sense, there for you?

Interesting debate, but does this matter?

It matters hugely, in any debate on how to spend limited public money well - which means every debate involving public money.

For one thing, there’s a question of how to value it, which is why public services are under constant pressure to show how many users they have. And on one level we are all Calvinists, in the sense that clearly a community with a higher proportion of women having children should have more midwives per head than one that’s predominantly made of the over 65s.

But more fundamental to this is the question on whether you provide it at all. Or, perhaps even more crucially, when considering what you need to cut? A council which takes a Calvinist perspective on libraries will be more likely to cut them. Why spend that money on the middle-classes when it could be going on the poor?

When I worked at the Department for Education, I regularly saw submissions that argued against particular policies because, even though they were open to everyone, the fact that they would be used more by the middle-classes was a reason not to do them. One example was a proposal, towards the end of the pandemic, that schools be funded to provide ‘enrichment’ activities after the end of the school day - after-school clubs, for those not used to educational jargon. There was serious concern by officials that unless these were made mandatory, there would be higher take-up by the wealthy than the poor, and so they would widen inequality. This was accepted by ministers10, but ultimately it was decided that mandatorily extending the school day for everyone would cost too much, and the initiative was abandoned.

That point about widening inequality is a crucial one. If an organisation’s objectives are focused primarily on ‘reducing inequality’ or ‘closing gaps’, then under a Calvinist lens, a universal services may be seen not just as disproportionately benefitting the wealthy, but as an actively bad thing - even though no-one is made better off. It is better, for those focused on reducing inequality, to help no-one than to help 100 poor children and 200 rich ones. Sadly, even under a Conservative Government, the Department for Education’s thinking was utterly dominated by ‘closing gaps’ - something I’m will sure will only increase further under Labour.

I do very much wonder whether public libraries - or the Open University - would stand a chance at getting started in today’s equality-of-outcome focused environment.

Of course, there are sometimes genuine questions to ask about whether a ‘universal’ service is genuinely open to everyone. Sometime’s it’s not, either because people didn’t care, or because they tried hard, but forgot to talk to or think of some of their potential users and overlooked something. One should definitely look at this.

But often, something is genuinely available to everyone. And whether one is Calvinist or Arminian about it really matters.

Let’s flip some assumptions

I’ve spoken so far as if the Calvinist lens is primarily used by those on the left, or at least by centrist utilitarians. And to a large extent that’s true. But we shouldn’t fall into the assumption that that’s always the case.

I spoke about a Tory education department being obsessed with ‘closing gaps’. And Conservative critiques of both Labour’s ‘Sure Start’ programme and the EU’s Erasmus exchange programme were rooted in the fact that these disproportionately benefitted the middle classes, rather than being well-targeted on the most needy.

But OK, you might say, that’s just right-wingers putting on left-wing clothes. So here’s a truly right-wing case, where the lens are flipped: are state schools for everyone, or only for those who attend them?

This time, it’s the left who have the Arminian approach. They typically argue that state schools are open to everyone, and if you choose not to send your children there and go to a private school instead, that’s your choice, but you shouldn’t expect any extra help from the state for that11.

After all, the state school was there for you; you just chose not to use it.

Here, it’s those on the right who are much more likely to take a Calvinist approach and argue that as those who don’t use state schools are not costing the Government money, the school is not there for them - and therefore support voucher schemes, which can be used to put towards the cost of a private school in education. Indeed, a number of states in America have recently begun operating ‘School Choice’ programmes, where public funds follow the child, meaning a parent who withdraws their child from state school receives an equivalent amount of funding12 that they can use for private schooling, tutoring, home schooling costs and so on.

So which perspective is right: Calvinism or Arminianism?

Agency. It’s all about agency

Ultimately, it’s all about agency.

The Calvinist view of public services falls down, just as Calvinism does13, in denying human agency. People are not automatons; they are able to exercise free will - and the library is there for them, whether they choose to use it or not. And there is no injustice if some make use of an opportunity offered to them whilst others do. The state is obliged to provide water, not to make people drink.

In fact, not content with Limited Atonement, the Calvinist approach to public services tends to swallow most of the rest of TULIP14. It is a view of the public - particularly of the more disadvantaged - that robs them wholly of agency, a form of total depravity15 in which people are rendered so helpless by their disadvantage that they are unable to exercise the free will to choose to use a service or not16.Indeed, we will often see the public service hectored for doing insuffient outreach, or not being ‘welcoming’ enough. If a centre-left policy wonk got to heaven, the first thing they would do is lecture God on not being sufficiently inclusive.

Agency, also, shows why the Arminian approach is also correct when thinking of who state schools are there for. They are genuinely there for everyone - and if parents choose to exercise their agency by choosing other options, that is their business. The state should not hinder them17, but nor is it obliged to compensate them for exercising their agency to not take up what was offered18. I’m not against voucher schemes, per se, but they seem very much superogatory, and unlikely to be the best use of public money.

Beyond philosophy, there’s another problem with the more simplistic Calvinist approach to universal services. And that is because the question of who benefits is more complex than just who uses it the most.

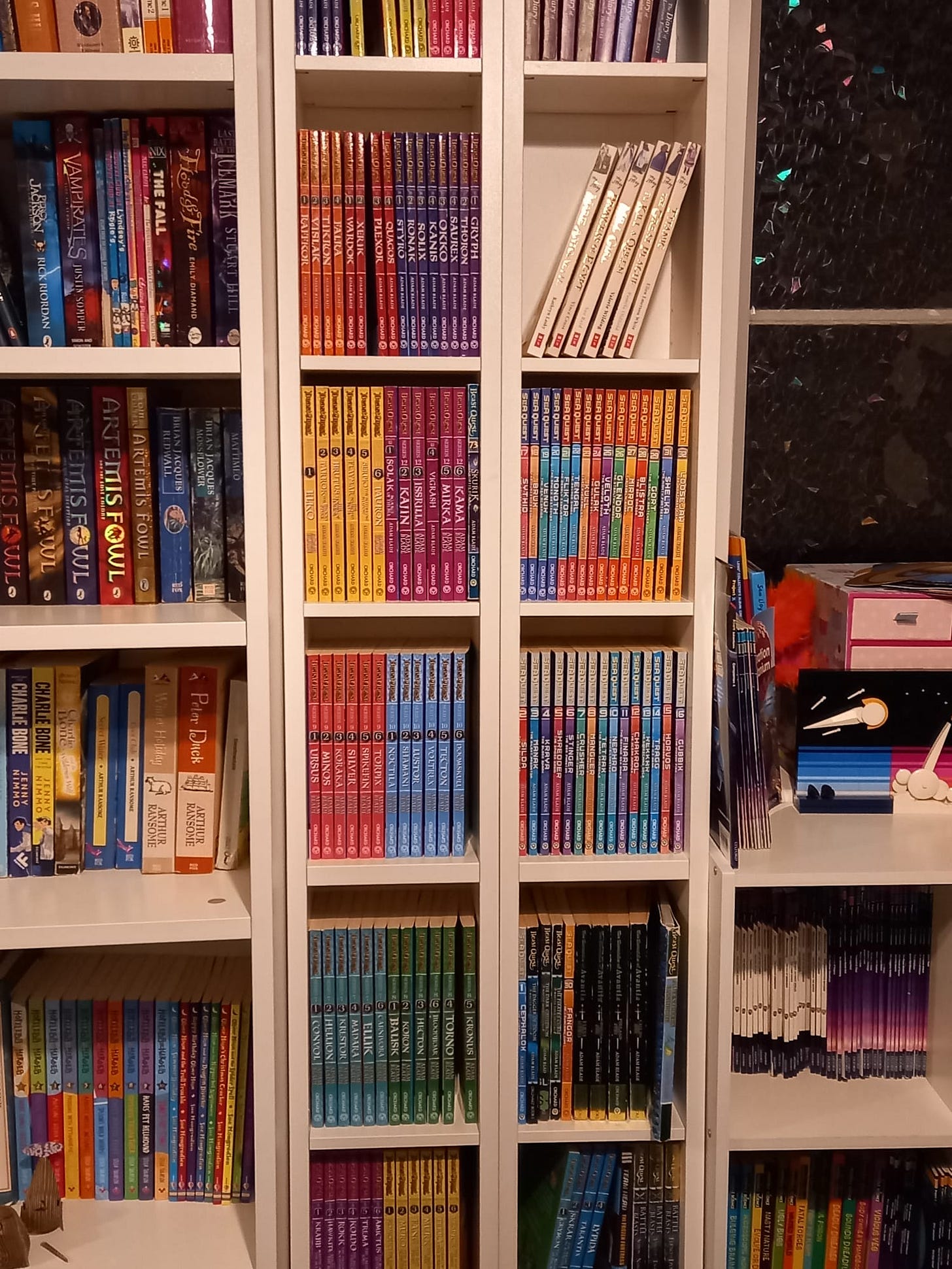

As an illustration, consider our 100+ collection of Beast Quest books

For the uninitiated, Beast Quest is a collection of series by a number of authors collectively known as ‘Adam Blade’. In each series, the protagonist must encounter and defeat one beast per book, in order to save a kingdom or some other such worthy goal. They are written to formula, highly simplistic and have the literary merit of a whelk’s autobiography.

The reason we have over 100 of them is that Eldest got into these just as the first lockdown began. They were their first real ‘chapter books’ to be read independently and they were getting through 2-3 a day. But the library was closed - so as we’re fortunate enough to be well-off enough to be able to do so, we just bought them. All 120 or so of them in however many series were out at the time.

And there’s the rub. It may be that proportionately more middle class families use libraries than poorer families, but if they all closed tomorrow - we’d be just fine. Our children would still have books: we’d buy them.

It’s the children of the families who can’t afford books, or whose parents don’t care to buy them, that would go without. The children for whom the library is their only gateway to a world of literature, wonderful stories, and escape. The children, like Matilda, for whom the library is a refuge and a gateway into a better world.

And it’s the same for all these services. Yes, buses are convenient for me19 - but I could drive. It’s nice to have free museums - but I could pay the fee. It’s great when schools offer clubs and societies - but I could pay for extracurricular activities are outside. Making them universal has two main benefits: (a) they continue to command widespread support; and (b) they stay high quality. When public services are only for the poor, they tend to become poor quality, because no-one with enough clout cares to make enough fuss to ensure they’re maintained.

The people who all of these free, universal services are for, most of all, are for those who cannot afford it. Yes, not all of them will take it up; perhaps most of them won’t. But it is still there for them. And will you deny the agency of those who do?

One thing that both Calvinists and Arminians agree on is that humanity is fallen. In more secular terms, humans are not perfect. Nor are they perfectible by the state - and any attempt to do so is doomed to fail.

The Arminian perspective is correct. Public libraries - and other services - are for everyone, whether they use them or not. The state has an important role in providing opportunities for everyone to better themselves - and should ensure they are genuinely accessible, and remove barriers to usage. But it is not for the state to ensure that everyone takes them up - nor should it blame itself if some choose not to.

Ultimately, it is for each person to decide on whether or not to respond to the opportunities offered.

And finally, an announcement…

I have - after 15 years - completed Visions in Exile, the sequel to my first novel, Imperial Visions. In a week or two, with thanks to some very good friends for help in various ways, it should be for sale on Amazon, in Kindle, paperback and hardback illustrated form.

I’ll also be releasing an updated version of Imperial Visions, with the first five - weakest - chapters significantly edited to improve readability and pacing. There are no plot or character changes, so no need to read again if you’ve already read it - but if you are coming fresh, it should be a significant improvement.

For a sneak preview, here’s the front cover, with tremendous thanks to A6 M8 - with more information to come very shortly.

.

Which yes, means it is slightly late, for which I apologise. I blame Rishi Sunak for calling a General Election I wasn’t expecting!

Technically speaking, he only managed to do the latter in the world of His Dark Materials.

Which the internet is at great pains to inform me is a gross simplification and does not reflect the full complexity of Calvinism, just in case we were under the misapprehension that the Institutes of the Christian Religion consisted of a single Powerpoint slide.

Why does the religion that emphasises total depravity, unconditional election and salvation through faith alone get the ‘Protestant Work Ethic’ bonus, while the religion which emphasises that salvation is achieved through both works and faith get the ‘southern European siesta culture’ malus’? Something is messed up here and someone really needs to submit a bug report to Uriel.

In fact, this was more or less his entire career.

We are now straying into Unconditional Election.

No Calvinists were harmed in the writing of this blog-post.

Any public facility is in some sense going to be more available to those who are retired/unemployed than those who work; to who can drive rather than those who rely on public transport. Our hypothetical library doesn’t offer individual free taxi rides to anyone who wants to use it, but equally doesn’t do anything directly or indirectly to keep them out.

To be clear, I am using Arminian and Calvinist here by analogy to public services. I’m not suggesting actual Arminians or Calvinists necessarily think this about them.

The issue of parental choice appeared to matter to almost no-one involved.

And, indeed, that you should be taxed for that privilege.

Or almost; a lot offer 80-90%.

What, you thought I didn’t have opinions about Calvinism, just because I don’t believe in God?

Though not the Perseverance of the Saints.

In the Calvinist sense.

This, of course, overlooks those who are equally poor who do choose to make use of this. Some immigrant communities, in particular, despite being desperately poor, tend to make huge use of educational opportunities offered to them, showing that poverty is not the principal barrier here.

For example, by taxing them.

I do, however, hold the niche view that the Government should fund exam entry fees for standard GCSE and A-Level exams for all children in independent schools or who are home educated. And the decision not to send the Jubilee Book to children in independent schools was simply petty and spiteful.

OK, buses are not convenient for me. Replace that with trains or the tube.

Congrats on the book! I should read the first one (although I'm somewhat afraid to because there have been a couple of people whose blogs I enjoy and whose novels I read as a result and really didn't enjoy and then felt kind of guilty. Even Unsong I did like but not as much as I like Scott's blogging.)

Can I make a suggestion on the cover design, or is it too late? It has a bit of an amateur self-published vibe, and I think this is because the text doesn't stand out very well from the background. The text is completely flat and monochrome, and the I in particular isn't very well distinguished from the mountain background. I think it might help if the text had a slight subtle outline or shadow, or maybe if you kept the existing text colour for the title (which is against the sky, so contrasts well) but put your name (which is against the darker mountains) in a different colour.

I really enjoyed this: the illuminating application of a non-obvious theological analogy to a contemporary political topic, the even-handed pointing out of an inconsistency/reversal in both left-wing and right-wing thinking, the entertaining asides, and the bonus Foundation reference.